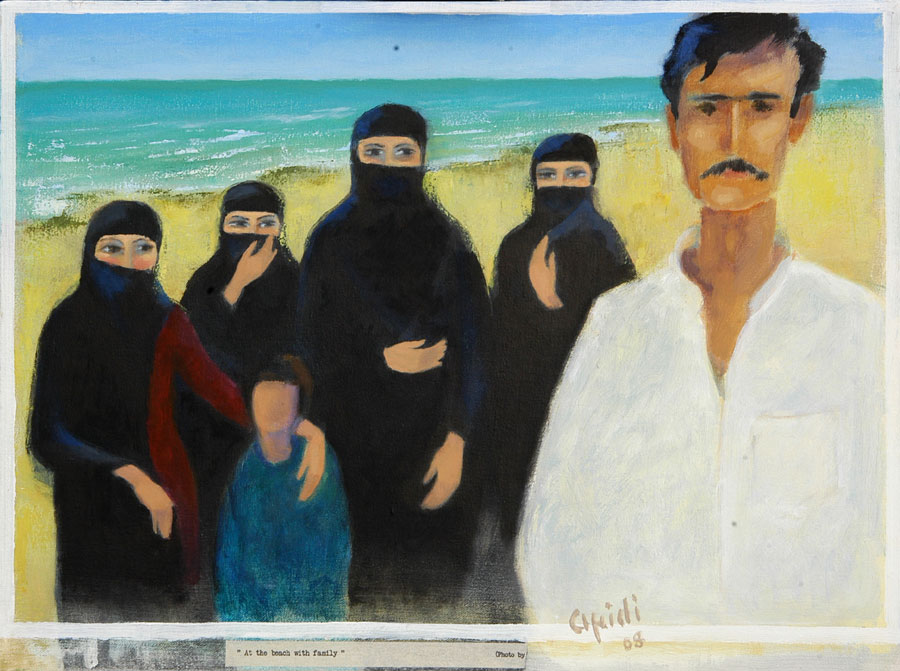

“At the beach with the family” by Jamil Afridi. Image courtesy of the ArtChowk Gallery.

A writer discusses prejudice and her desire to live in a more tolerant world

By Supriya Bhatnagar

In the Summer of 2001, on our annual visit home to India, my husband Anil decided that a goatee would look nice on his face — or rather Caroline at work had suggested that it would look nice and he decided to give it a try. After several days of Anil not shaving and looking like a drunkard with a perpetual hangover, and over mixed reactions from family and friends, the beard took shape. It looked nice, I had to admit to myself, but I secretly dreaded the amount of time he would spend on it each morning, making him late for work. Anil is not one of those who wakes up with the first light of day to be greeted by the melodious sound of chirping birds and to the smell of freshly brewed coffee. In fact, that is the time when he is in his deepest sleep. His very mathematical mind has him calculating how much time it takes for him to do every task between waking and leaving for work, and he does not get up a minute earlier. But goatees need looking after. They need careful grooming, close inspection, proper shaping, and a very steady hand while shaving.

On the way back to the United States from India, as we waited at the airport in Vienna for a connecting flight, a Middle Eastern woman walked up to Anil and asked him, “You Arab?†Wow! I thought. My husband looks like a Sheikh. My girlhood fantasies about being swept off my feet by a rich oil tycoon with light skin, deep black hair, an even deeper voice, and piercing black eyes had come true — well almost; the filthy rich oil tycoon part will never happen.

Soon after our return, peace was shattered and the world was in turmoil over the terrorist bombings on The World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Washington, DC. “Attack on America!†the headlines called out. America’s war against terrorism was on. There were frantic calls from home, wanting to know if we were safe. Fortunately for us, no one we knew was a victim of this tragedy, but that did not lessen the horror and grief over what happened to thousands of others. Reading the newspaper every morning about the losses brought tears to my eyes. Amidst all that horror, we went about our lives — working, studying, cooking, cleaning, and also enjoying, with one change. Anil’s goatee had to be shaved off.

On the way back to the United States, as we waited at the airport in Vienna for a connecting flight, a Middle Eastern woman walked up to Anil and asked him, “You Arab?†Wow! I thought. My husband looks like a Sheikh.

The question that the woman in Vienna had asked haunted us. He looked Arab to her and we did not want anyone to think that he was a Muslim. Our friends called to say that the beard was a bad idea. Our parents called from home insisting that he shave the beard off. I felt terrible. In the month between our return from India and the September 11 attack, we had all become used to the beard. Surprisingly, his peppery beard was soft to the touch and didn’t prick when I kissed him. Caroline at work loved it. “Makes you look very distinguished,†the women at work crooned, inflating Anil’s ego. The kids protested, “Please Papa! You look so nice.†As for me, my life with a Sheikh was over. But we had to be practical. Beards could be grown again, maybe not a masterpiece like this one, but something similar. It took Anil more than an hour to become clean-shaven again. Beards, I found out, cannot be just shaved off. First they have to be trimmed as close to the skin as possible. Then starts the decision about how long the moustache, which remained, should be and how thick and what shape. Should it taper off at the end? The kids and I watched, saying goodbye to one Anil while welcoming the old one back.

*

We Are Hindus, I want to scream to the world. Please do not look at us like that. It is Muslim fanaticism that perpetuated this tragedy — not the Muslim faith. Anil and I grew up in India where diversity and many religious faiths are a way of life. Secularism was taught in schools. Our classmates were Hindus and Christians and Muslims. We learnt about Ram and Krishna and about Christ and His Apostles and also about the Prophet Mohammed. At prayer meetings, we sang hymns that said that the Gita and the Qur’an are the same; Ram and Rahim are one.

Despite all this, Hindu-Muslim rioting in India is commonplace and blood flows freely during these disturbances. I’m sure neither Lord Rama, nor the Prophet Mohammed, foresaw the death and destruction wreaked by their followers in Ayodhya in 1992, when Hindu radicals decimated a 16th-century mosque, saying that the Muslims had desecrated the birthplace of Ram. In retaliation, the Muslims razed to the ground the temple that the Hindus built in place of the destroyed mosque. The beauty of the architecture was lost to the masses and Ram killed Rahim and Rahim killed Ram; over 3,000 people lost their lives.

One weekend, as part of our Friday evening movie watching ritual, Anil and I drinking wine and the kids drinking soda, we watched the Hindi movie Gadar. It is a story about the love between a Sikh boy and a Muslim girl during the 1947 Partition when India and Pakistan became two. Just as we find it hard to get over the terrorist attacks here in the U.S., India is still trying to come to grips with something that happened half a century ago.

It was a painful period in India’s history when she lost a limb, and Muslims and Hindus were separated forever. Neighbors and friends turned against each other. Ram and Rahim became enemies, and religion reigned supreme. Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s founding father, was adamant. He wanted a separate Muslim state. Mahatma Gandhi gave in and lost his life to a madman as a result. Nathuram Godse, like many other Indians of the time, blamed Gandhi for the Partition and put a bullet through the Mahatma’s heart. Hey Ram! said Gandhi before falling to the ground.

In the movie Gadar, Sunny Deol rescues Amisha Patel, a Muslim girl left behind in India during the melee of Partition. Their love for each other is deep and committed, but her parents, who are now in Pakistan, find out and are livid. She has married an infidel they say and try to separate them. Of course, love prevails, and we have a happy ending. It wouldn’t be a blockbuster Hindi movie had it ended otherwise, now would it? Sunny Deol is a muscular and handsome Jat, and Amisha Patel is beautiful in her colorful salwar kameez sets; I want to dress like that. The designer’s talent shows in the period costumes. I love the deep rich shades of her kurta and the contrasting dupattas. I like the way she covers her head and the long clinging sleeves. Even though she is covered from head to foot, she manages to look sexy.

But I am a Hindu. How can I even think of dressing like a Muslim? I remember Mummy, who was a young girl in the years following Partition, saying that she could not play badminton during her college years as it required her to wear the salwar kameez. My grandfather, a doctor and very progressive otherwise, put his foot down. We are South Indians, he told Mummy, and like other girls who are not old enough to wear the sari she had to wear a long ankle length skirt, a blouse, and a long davani, that draped around and covered her chest. This intolerance to something Muslim was restricted to just the way of dressing, however. Mummy and her siblings had Muslim friends who came over and she could visit their houses too — and even eat meat with them. Muslim Nizams ruled the southern state of Hyderabad before India’s independence. My grandfather had many Muslim patients, and during communal riots they trusted him with their jewelry and material wealth. I can only attribute his aversion to the Muslim way of dressing to his upbringing.

It was a different story in northern India. Partition had deeply wounded the North. Whole families had been lost or separated. People from both sides had fled leaving everything behind. Most families had lost a son or a brother or an uncle or a father to the rioting. Anil’s grandfather’s family had fled Lahore, now in Pakistan. Naniji, his grandmother, in her nineties when she died a few years back, had become confused with everyday matters in her old age, but retained vivid memories of those days. “We left behind expensive Persian carpets, gold, silver, furniture, utensils, and much more†she would say again and again. She had forgotten her family, and relationships held no meaning for her anymore, but she still felt the pain of all that was lost during Partition.

One of the warmest memories of my childhood is sitting around the warm angeethi, the clay stove, in the Khurana household during cold winter nights eating hot and spicy Muli Parathas topped with melted butter. The Khuranas were the only family I knew personally before I met Anil’s who had lived through the tortures of Partition. They were from Multan, now in Pakistan, and Mrs. Khurana was a young girl when the exodus of Hindus from Pakistan to India took place. Her husband’s family was part of that move too, although she did not know him then. Both lost family members and both remember first hand the horrors of the time. Once in India, they lived in refugee camps at the mercy of the government. How humiliating it is to start life all over again from scratch. It is so easy for us to get used to our material possessions; so difficult to let go. I think of all those Afghani men, women, and children in tents in Pakistan in frigid temperatures. The Taliban is destroying its own.

India is now in the process of losing the generation that lived during those horrible times, and the wounds are not as deep. Partition is something we study in history books or relive by romanticizing it in movies like Gadar. It is a period in history that novelists and filmmakers use as inspiration. In a burst of patriotic fervor, I have attempted poetry, but failed miserably. Instead, I have often fantasized about being born then, during India’s struggle from British rule. I too would have worn khadi, the homespun cotton cloth that Gandhi wanted us to wear and I would have boycotted everything British. I too would have taken part in marches shouting “Inquilab Zindabad!†I would have gone to prison gladly in defiance of British rule, and during Partition, I would have been one of the many who provided a safe haven to the fleeing and hunted Muslims.

India today is predominantly a Hindu state with about eighty percent of the people following this faith. She is second only to Indonesia in her Muslim population, which comprises the largest section of the remaining twenty percent, followed by the Christians, the Sikhs, the Jains, the Parsis, and very few Jews. There are pockets of Muslim community in every city, but unlike my mother’s, my memory is restricted to an occasional visit to a Muslim family’s house during the festival of Id. My other fantasy, apart from being a freedom fighter, was to have been born a Muslim so I could raise my hand and greet people saying Salaam Wale Qum as they did. It is one of the most graceful gestures known to mankind. I wanted to cook and eat mutton as they did. The gravy is thin and red, colored by chili powder, and the thought of dipping large thin Rumali Rotis in it is pure ecstasy.

“Marry someone from your own faith,†my mother, despite all her interaction with the Muslim community, would tell my sister and me when we were teenagers, “and you will have no problem adjusting.†I did not agree with her, but did not argue otherwise either. It is the person we are marrying who matters, not the faith, I would think, not having the courage to tell her so. Today, I am ashamed to say that I am relieved that neither am I a Muslim and nor did I marry one. Why is this so? Is it that I am scared? Had I been a devout Muslim, I would have had the strong conviction that it is not my God who attacked The World Trade Center or the Pentagon. My husband would not have shaved off his beard either. In the years since the attack, we have forgotten Anil’s beard. Has he? His reasons for growing the beard were purely egotistical. It made him look nice. And he removed it only to give our parents peace of mind. Occasionally he would rub his fingers on his bare chin and ask, “It did look good, didn’t it?â€

In any case, marrying a Muslim is not very easy. A non-Muslim girl marrying into the Muslim community has to convert to the Islamic faith first. This bothers both Anil and me immensely. Why can’t we follow our own religion and at the same time respect the other’s? Amongst the Parsis of India, the followers of Zoroastrianism, the rules are stricter. Even if a Parsi boy marries outside his community, he is immediately ex-communicated. No wonder the Parsi community in India is fast dwindling.

Today, I am ashamed to say that I am relieved that neither am I a Muslim and nor did I marry one. Why is this so? Is it that I am scared? Had I been a devout Muslim, I would have had the strong conviction that it is not my God who attacked The World Trade Center or the Pentagon. My husband would not have shaved off his beard either.

India’s relationship with Islam has been a long and arduous one. A major chunk of our history books deals with the Muslim invasions from the northwest frontier. The looting, the raping, the killing, and the desecrating are all part of it. It was finally Akbar the Great, during the rule of the Moghuls some five hundred years back, who decided that Hindus had to be pacified if there was to be peace. In a masterstroke of diplomacy, he married Jodha Bai, a Rajput princess from Rajasthan, to show his tolerance towards Hinduism. What an enormous impact that must have had on the general population — a mighty Moghul marrying a Hindu princess! He managed to win over the hearts of his subjects immediately.

Akbar and other Moghul rulers were different from barbaric invaders like Chengiz Khan and Timur the Lame. They promoted art and architecture in India. Music and poetry flourished in their Courts. One of the greatest love stories in Indian history is that of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jehan and his wife Mumtaz Mahal. The Taj Mahal in Agra stands as a testimony to this love. Shah Jehan’s love for his wife and his building of this monument to her memory has been immortalized in song, dance, and poetry. Large Mughal paintings to tiny miniature ones, one of the greatest legacies of the Mughal Empire, depict this famous couple. And in every Mughal painting, there is one thing in common — all men have beards.

Now that a big deal was made of Anil’s tiny goatee, I was curious to know just what a beard meant to a Muslim. According to scholars of the Qur’an, the mustache has to be trimmed but the beard has to be grown to at least fist length if not longer. Actually, a goatee in no way resembles the traditional Muslim beard, but the fact that there is hair on the chin combined with the fact that an Indian can easily be mistaken for a Middle Eastern is what caused this explosive situation. Soon after the September 11 attack, an Indian Sikh in Arizona was shot dead. If a Sikh does not dress his beard in the proper way, it does look like a flowing Muslim beard, but then the turban they wear is very different from the Arabic one. That poor misguided bastard who shot the Sikh did not know this.

And it is this ignorance that scares me. Now that his beard is off, is my husband actually safe? Does he still look like an Arab? I have an Afghani friend. My neighbors are Afghani. The gardener who looks after my shrubs is Afghani. How do I protect them? I am helpless. On the television, we watched as President Bush, Colin Powell, the Reverend Jesse Jackson, the Pope, and many others urge the people not to blame Islam. Not to blame the people of Afghanistan. Will the people listen? Will a madman shoot someone just because he looks like one of the terrorists? These days I find myself praying to God for revenge. I pray to God for the souls of the dead. In India, I have visited the shrine at Velankani for the infant Jesus in Chennai. In Ajmer, I remember going to the Dargah of Sheikh Salim Chisti, a Muslim Sufi saint. I do not want Hinduism to reign supreme, but neither do I want Christianity, or Islam, or Judaism to rule the world. I want people to rule.

Just as the Muslim world’s hatred of the Western world is deep-seated, so is prejudice against Muslims amongst Hindus. This lack of tolerance can be seen at every level. If today I were to appear before the grandmothers of my community without a bindi on my forehead, they wouldn’t hesitate to ask why I insisted on looking like a Muslim. How can I tell them that actually, I’d like to look like a Muslim? I would like to look like the film actress Rekha in Umraao Jann. She plays a beautiful courtesan and her dresses and jewelry are exquisite. I would like to dance like her and sing like her. I would like to learn Urdu, an extremely polite and refined language.

This narrow-mindedness towards the other’s faith is not restricted to Hindus and Muslims only. Christianity in India has its history too, beginning with the arrival of Christ’s own Apostle, St. Thomas, who landed in Mylapore in southern India. There are families in the southern state of Kerala, who say with pride, “We are old Christians.†Patriotic songs belt out lyrics full of the brotherhood of Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Isaai (Christian). If we are used to Christianity for the past two millenniums, then, why do we still kill Christian missionaries in the jungles of East India? Radical Hindus, just as there are radical Muslims, are everywhere, and the thread of their tolerance towards the other is as thin as the narrow strip of land that runs from mainland Mumbai to the Haji Ali. Bearded and capped Muslim men and burkha-clad Muslim women cross over to this mosque to pray to their God. The waves that lap at the shores of this island retreat also wash away the blood of the people of Mumbai — Hindu, Muslim, and Christian — who kill each other in the name of religion.

Speaking of Christianity, I haven’t thought about Mrs. Peters in a while — for more than thirty years now actually. She lived in that corner house by the big water tank in Jaipur and I would often see her walking around our neighborhood. She would knock on peoples’ doors and hand them a Bible saying that that the world is coming to an end. Her firm conviction was that reading the Bible and embracing Christianity would somehow prevent this terrible doom and keep our universe from disintegrating. Very soon, at the sight of Mrs. Peters walking down the street, people would either shut their front doors in a hurry saying “the crazy woman is doing her rounds†or actually invite her in, listen to her talk, politely accept the Bible, and then forget all about her and the holy book as soon as she left. The futility of this mission seemed to evade Mrs. Peters as day in and day out she insisted on converting an entire neighborhood of middle-class, religious-minded Hindus into Christians.

One evening, Mrs. Peters walked into to my mother’s sister’s house. Jayu Aunty is a doctor and a moderately devout woman who after years of dealing with brash medical students does not hesitate to speak her mind. She listened politely to Mrs. Peters’s theory about the world coming to an end, went in, and came out with the Bhagwad Gita, which she handed to the speechless woman. Jayu Aunty told Mrs. Peters that she would read the Bible as an exchange, only if the other woman would read the Gita. “We don’t have to convert to read the Bible,†she told Mrs. Peters, “and what’s in the Bible is in the Gita too. You say the world is coming to an end, and we say it is Kalyug, and we too are awaiting the coming of the Lord, our savior.â€

Now I am beginning to think that Mrs. Peters was right after all. The world as we know it does seem to be coming to an end. We are afraid to step out of our homes, afraid of going to public places, and even afraid of opening our mail. I want to take my children to the museum, but hesitate—will a madman blow it up while we are inside? I want them to see the world as I have, have a carefree childhood, and not be afraid.

An overwhelming sense of sadness engulfs me as I think that they can never visit places like the Kashmir Valley. Through my mind’s eyes I relive the moment when just before getting married and leaving India, I went to Srinagar to attend a cousin’s wedding. It was an overnight journey in The Jammu Express, which took my family and me from New Delhi to Jammu, and from there we had to take the bus for a whole day’s journey to Srinagar. I remember sitting by the window, resting my forehead against the windowpane, and taking in the exhilarating beauty of the countryside. The snow capped Himalayas formed a distant border to this picture-postcard scenery. Even though our bus had huge windows, the frame was restricting. I wished the roof would fold open and I could stand up and stick my head out to breathe everything in.

The road to Srinagar is untouched rugged beauty not spoilt by man. It meanders through the hills and valleys with green meadows on either side. I remember looking down once as the bus went on a rickety bridge over a sparkling brook in which I could see the rounded pebbles at the bottom of the clear water. Closer to Srinagar, tall fragrant eucalyptus trees border the road, their white trunks matching the distant peaks. The fresh mountain air is made healthier by the presence of these trees, whose leaves are known for their medicinal properties.

It was almost nightfall by the time the bus reached Srinagar. Bathed in the soft glow of yellow electric bulbs, the entire town seemed to shun the harsh glare of tube lights. The dimness took some getting used to, but I realize now that it was better that way. It gave the whole place a dreamy look against the stunning backdrop of the mountains that are visible from even the most congested spot in the marketplace.

Kashmir is teeming with Muslim militants now. People are afraid to go there. Hindus have fled, leaving their properties and their hearts behind. Some day in the future, I will take my children to this valley, often called the Switzerland of India. I want them to get out of the bus so they can put their hands in the cool rushing water of the wayside brook. I want them to stick their heads out of the window to breath in the air free of pollution. I want to show them that God did come down once, leaving behind Him a piece of heaven for us to savor.

Supriya Bhatnagar has a B.Com degree from the University of Rajasthan, India, a BA in nonfiction writing and editing, and an MFA in creative nonfiction from George Mason University. Her memoir, ‘and then there were three…’, was published in 2010 by Serving House Books. She is the Editor of the Writer’s Chronicle and a Pushcart Prize nominee.