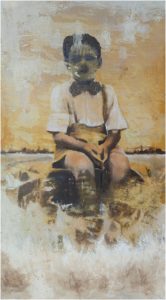

Artwork by Naira Mushtaq. Image courtesy of ArtChowk Gallery.

We have all got to exert ourselves a little to keep sane, and call things by the same names as other people call them by.

—George Eliot, Middlemarch

Bettina Oberholzer rubbed her eyes and read the letter again:

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Oberholzer:

Pursuant to your application to the cantonal authorities, we inform you that a male child currently under the care of our institution is available for adoption. The child is approximately two years of age, and is believed to have been born in late December. You will be given first option among the various candidates on file, provided that your response to this letter reaches us within twenty days from the date of mailing.

Yours faithfully,

Todikon Orphanage

Regina Aeppli, Director

The young woman picked up the telephone on the kitchen table and started to dial, stopped herself in midstream, and hung up. “I’ll tell him when he comes home,†she said aloud. “I don’t know what kind of mood I might catch him in at the bank.â€

As Martin Oberholzer hung up his raincoat in the corridor that evening, he smelled the afterscent left by a baking chocolate cake. Bettina only made cakes when there was cause for celebration. He sauntered nonchalantly into the kitchen and folded his wife in his arms: “What kind of day did you have?â€

“A red-letter one, that’s what kind!â€

“Tell me all about it.â€

With a radiant face, Bettina handed him the letter. “This will explain everything.â€

As usual, Martin Oberholzer expressed his pleasure obliquely. “What a language!†he exclaimed. “The good woman might be writing about a boxcar of spinach to be picked up before it spoils!â€

“Never mind. That’s just the way bureaucrats write. The important thing is what she says.â€

“It certainly is. We’ve been waiting over a year now.â€

The couple embraced and stood silent for a moment, listening to the patter of the raindrops outside. The perfume of the lilac bushes in the Carmenstrasse wafted in through a crack in the window.

“As I see it, the boy must have just been put in the orphanage,†Bettina reasoned. “With the demand nowadays, he couldn’t have been there long without being adopted already. I wonder why his parents…I wonder, and still…â€

“Let’s stick to what we agreed,†Martin interrupted with some force. “He’s going to be ours now. Whoever his biological parents were or are makes no difference.â€

“You’re right. But I can’t help asking myself why the director’s so vague about his age. She believes he was born in late December. What can that mean?â€

“It’s irrelevant. If they don’t know his exact birthday, then we’ll give him one. What about Christmas Day?â€

“A wonderful idea!†Bettina agreed. “And his new name is waiting for him too: Thomas Oberholzer. Thomas for both his grandfathers—but then, he’ll already have a name, won’t he? They surely call him something at the orphanage.â€

“It doesn’t matter! Whatever it is, we don’t need to know it. Any more than we need to know who his biological father and mother were.â€

And little by little, with the help of Bettina’s dinner and a bottle of Mouton Rothschild, the joy of the two parents-to-be rose to concert pitch. The providers of the two cells that had made it all possible slunk further and further away into a murky background, like specters cringing back from torches. But somehow, even after the chocolate cake and the kirsch, they had not disappeared entirely.

* * *

The building blocks lay scattered across the room, Donald Duck in pieces on the carpet. Shreds of the new pajamas hung from the Christmas tree. Tommy was banging the model racing car on the coffee table; the glass top had already shattered.

“Merry Christmas, Tommy! Happy birthday!â€

Mistletoe and cedar garlanded the living room. Tinsel, china angels, and bits and bobs of colored glass glittered on the small pine tree by the window. The white candles had been lit the night before; only hardened puddles of wax remained in the holders this morning.

Little Thomas Oberholzer, three years old on this his putative birthday, sat by the tree and glowered at it. The child’s pale skin set off his flashing black eyes. Luxuriant black hair crowned the little head with curls; long black lashes adorned the eyes.

Bettina pulled a red-wrapped box from under the Christmas tree. “Let’s open this one first. This is from Papi and Mami, for Christmas.â€

The boy and his mother tore the red paper away and brought to light a set of many-colored building blocks.

“That’s what I liked best of all when I was your age,†Martin told his son.

“Building blocks.†Bettina enunciated the words carefully and looked expectantly at the boy.

“Chewing gum,†the child said in a loud guttural voice.

The mother tried another word: “Papi.â€

“Parrot!†yelled the boy.

“Mami.â€

Tommy snatched up a red building block and threw it hard into his mother’s face. It struck the bridge of her nose.

“All right, young man!†Martin cried. “You asked for this.†Not gently at all, the father pushed the boy down on the floor, turned him over on his stomach, and whacked his posterior.

“Martin!†Bettina protested. “It’s Christmas, and his birthday too.â€

“That doesn’t give him license to behave like this. Nothing does. I just won’t have it.†The father’s voice quivered with barely contained fury.

Tommy sat up and gaped at the two adults with hard, dry eyes. He seized a building block in each hand and waited.

Bettina forced a bright smile. “Now Tommy didn’t mean to do that, did he? I’m sure he didn’t. Let’s see what else we find under the tree.â€

A gold package with a crimson bow came forth.

The boy let his mother open the present by herself, clutching his blocks like weapons. “Isn’t this nice!†Bettina crowed, lifting a model racing car out of the wrappings. “Can you say car, Tommy?â€

The boy hit his mother’s pitch exactly, but gave back another word: “Potty.â€

Martin made clicking noises with his tongue, a sign, as his wife well knew, that his patience was running out. And the man’s supply of patience, at any given moment, seemed to be lessening. It had been so ever since they had driven to Todikon to fetch their son and heir.

“What about this nice blue box?†Bettina asked the boy. “What do you suppose is inside it? Let’s see now…â€

One by one, the presents offered the boy by Samichlaus, by his adoptive parents and grandparents for his first Christmas in the Carmenstrasse were unsheathed. For the most part, the recipient refused to call them by their names. He tacked other words onto them, words that struck his two listeners as bizarre.

“I can’t stand much more of this,†Martin said after the last package had been disposed of. A leaden fatigue resounded in his words.

“It’s all right, Martin,†Bettina rejoined. “The pediatrician said love and patience will do it. It’s just a temporary phase. She said…â€

“I know, darling. I’m sorry. I’m going to stretch out for a minute, and then I’ll be fine.†The 31-year-old man shuffled toward the bedroom in the same way that his grandfather dragged about in the retirement home.

Bettina stacked up some building blocks in front of the boy. “Now Mami’s going to help Papi get settled for a little rest. It will only take a minute. Let’s see what Tommy can make with the blocks while she’s gone.†After glancing round the room with a worried air, she hastened down the corridor after her husband.

When she came back fifteen minutes later, Bettina Oberholzer stopped dead under the mistletoe in the entranceway. The building blocks lay scattered across the room, Donald Duck in pieces on the carpet. Shreds of the new pajamas hung from the Christmas tree. Tommy was banging the model racing car on the coffee table; the glass top had already shattered.

“No,†she groaned. Tears filled her eyes and overflowed. “No. It can’t be. What are we going to do with the boy? What’s wrong with him?â€

When he heard the words, Tommy ceased to bang and ogled the woman in the door. Her whole body trembled as she returned his gaze. For in his expression she read an emotion that transcended her own person and her husband’s: an archaic hatred that had been old before the world was.