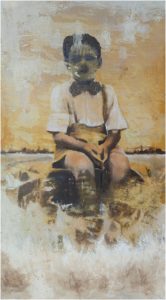

Artwork by Naira Mushtaq. Image courtesy of ArtChowk Gallery.

We have all got to exert ourselves a little to keep sane, and call things by the same names as other people call them by.

—George Eliot, Middlemarch

Bettina Oberholzer rubbed her eyes and read the letter again:

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Oberholzer:

Pursuant to your application to the cantonal authorities, we inform you that a male child currently under the care of our institution is available for adoption. The child is approximately two years of age, and is believed to have been born in late December. You will be given first option among the various candidates on file, provided that your response to this letter reaches us within twenty days from the date of mailing.

Yours faithfully,

Todikon Orphanage

Regina Aeppli, Director

The young woman picked up the telephone on the kitchen table and started to dial, stopped herself in midstream, and hung up. “I’ll tell him when he comes home,†she said aloud. “I don’t know what kind of mood I might catch him in at the bank.â€

As Martin Oberholzer hung up his raincoat in the corridor that evening, he smelled the afterscent left by a baking chocolate cake. Bettina only made cakes when there was cause for celebration. He sauntered nonchalantly into the kitchen and folded his wife in his arms: “What kind of day did you have?â€

“A red-letter one, that’s what kind!â€

“Tell me all about it.â€

With a radiant face, Bettina handed him the letter. “This will explain everything.â€

As usual, Martin Oberholzer expressed his pleasure obliquely. “What a language!†he exclaimed. “The good woman might be writing about a boxcar of spinach to be picked up before it spoils!â€

“Never mind. That’s just the way bureaucrats write. The important thing is what she says.â€

“It certainly is. We’ve been waiting over a year now.â€

The couple embraced and stood silent for a moment, listening to the patter of the raindrops outside. The perfume of the lilac bushes in the Carmenstrasse wafted in through a crack in the window.

“As I see it, the boy must have just been put in the orphanage,†Bettina reasoned. “With the demand nowadays, he couldn’t have been there long without being adopted already. I wonder why his parents…I wonder, and still…â€

“Let’s stick to what we agreed,†Martin interrupted with some force. “He’s going to be ours now. Whoever his biological parents were or are makes no difference.â€

“You’re right. But I can’t help asking myself why the director’s so vague about his age. She believes he was born in late December. What can that mean?â€

“It’s irrelevant. If they don’t know his exact birthday, then we’ll give him one. What about Christmas Day?â€

“A wonderful idea!†Bettina agreed. “And his new name is waiting for him too: Thomas Oberholzer. Thomas for both his grandfathers—but then, he’ll already have a name, won’t he? They surely call him something at the orphanage.â€

“It doesn’t matter! Whatever it is, we don’t need to know it. Any more than we need to know who his biological father and mother were.â€

And little by little, with the help of Bettina’s dinner and a bottle of Mouton Rothschild, the joy of the two parents-to-be rose to concert pitch. The providers of the two cells that had made it all possible slunk further and further away into a murky background, like specters cringing back from torches. But somehow, even after the chocolate cake and the kirsch, they had not disappeared entirely.

* * *

The building blocks lay scattered across the room, Donald Duck in pieces on the carpet. Shreds of the new pajamas hung from the Christmas tree. Tommy was banging the model racing car on the coffee table; the glass top had already shattered.

“Merry Christmas, Tommy! Happy birthday!â€

Mistletoe and cedar garlanded the living room. Tinsel, china angels, and bits and bobs of colored glass glittered on the small pine tree by the window. The white candles had been lit the night before; only hardened puddles of wax remained in the holders this morning.

Little Thomas Oberholzer, three years old on this his putative birthday, sat by the tree and glowered at it. The child’s pale skin set off his flashing black eyes. Luxuriant black hair crowned the little head with curls; long black lashes adorned the eyes.

Bettina pulled a red-wrapped box from under the Christmas tree. “Let’s open this one first. This is from Papi and Mami, for Christmas.â€

The boy and his mother tore the red paper away and brought to light a set of many-colored building blocks.

“That’s what I liked best of all when I was your age,†Martin told his son.

“Building blocks.†Bettina enunciated the words carefully and looked expectantly at the boy.

“Chewing gum,†the child said in a loud guttural voice.

The mother tried another word: “Papi.â€

“Parrot!†yelled the boy.

“Mami.â€

Tommy snatched up a red building block and threw it hard into his mother’s face. It struck the bridge of her nose.

“All right, young man!†Martin cried. “You asked for this.†Not gently at all, the father pushed the boy down on the floor, turned him over on his stomach, and whacked his posterior.

“Martin!†Bettina protested. “It’s Christmas, and his birthday too.â€

“That doesn’t give him license to behave like this. Nothing does. I just won’t have it.†The father’s voice quivered with barely contained fury.

Tommy sat up and gaped at the two adults with hard, dry eyes. He seized a building block in each hand and waited.

Bettina forced a bright smile. “Now Tommy didn’t mean to do that, did he? I’m sure he didn’t. Let’s see what else we find under the tree.â€

A gold package with a crimson bow came forth.

The boy let his mother open the present by herself, clutching his blocks like weapons. “Isn’t this nice!†Bettina crowed, lifting a model racing car out of the wrappings. “Can you say car, Tommy?â€

The boy hit his mother’s pitch exactly, but gave back another word: “Potty.â€

Martin made clicking noises with his tongue, a sign, as his wife well knew, that his patience was running out. And the man’s supply of patience, at any given moment, seemed to be lessening. It had been so ever since they had driven to Todikon to fetch their son and heir.

“What about this nice blue box?†Bettina asked the boy. “What do you suppose is inside it? Let’s see now…â€

One by one, the presents offered the boy by Samichlaus, by his adoptive parents and grandparents for his first Christmas in the Carmenstrasse were unsheathed. For the most part, the recipient refused to call them by their names. He tacked other words onto them, words that struck his two listeners as bizarre.

“I can’t stand much more of this,†Martin said after the last package had been disposed of. A leaden fatigue resounded in his words.

“It’s all right, Martin,†Bettina rejoined. “The pediatrician said love and patience will do it. It’s just a temporary phase. She said…â€

“I know, darling. I’m sorry. I’m going to stretch out for a minute, and then I’ll be fine.†The 31-year-old man shuffled toward the bedroom in the same way that his grandfather dragged about in the retirement home.

Bettina stacked up some building blocks in front of the boy. “Now Mami’s going to help Papi get settled for a little rest. It will only take a minute. Let’s see what Tommy can make with the blocks while she’s gone.†After glancing round the room with a worried air, she hastened down the corridor after her husband.

When she came back fifteen minutes later, Bettina Oberholzer stopped dead under the mistletoe in the entranceway. The building blocks lay scattered across the room, Donald Duck in pieces on the carpet. Shreds of the new pajamas hung from the Christmas tree. Tommy was banging the model racing car on the coffee table; the glass top had already shattered.

“No,†she groaned. Tears filled her eyes and overflowed. “No. It can’t be. What are we going to do with the boy? What’s wrong with him?â€

When he heard the words, Tommy ceased to bang and ogled the woman in the door. Her whole body trembled as she returned his gaze. For in his expression she read an emotion that transcended her own person and her husband’s: an archaic hatred that had been old before the world was.

“Ursi Beck! It’s been ten years since we saw each other last. And this must be little Margaret. Come in.â€

Bettina Oberholzer led the visitors into the living room flooded by the sunshine of a bright October day.

“I’m Ursi Blackburn now. When we finished school, I went off to Johannesburg to work, and I’ve been there ever since. Believe it or not, this is the first time in all those years that I’ve been home long enough to be able to hunt up old friends.†English inflections echoed in the woman’s dialect.

The sunlight faltered and dimmed as Tommy appeared at the living room door. Bettina switched on a bright, determined smile. “Margaret, this is my little boy. His name is Tommy, and he’s four years old. Would you like to see his toys?â€

The South African girl turned uncertainly to her mother.

“Of course she would,†Ursi Blackburn said. “She’d enjoy that. They’re the same age.â€

Margaret walked gingerly toward the boy, who disappeared from sight abruptly. Spurred on by curiosity, she ran to the doorway, saw Tommy down the corridor and pursued him. The door to his room closed behind the two of them.

“It’s amazing how children can entertain each other for hours, isn’t it?†Margaret’s mother commented. “Now listen, is Martin still with the bank? How long did you fly for Swissair? I want to know everything.â€

“So do I,†replied Bettina. “Let’s go out to the kitchen, and I’ll make coffee.â€

Twenty minutes later the slam of a door and a scream broke the thread of reminiscence. Stark-naked, Margaret rushed into the living room, shrieking for her mother, just as the two women hurried in from the kitchen.

“Mommy,†the child sobbed, “don’t let him hurt me. I’m afraid of him.â€

Ursi Blackburn’s face turned to stone. “What did he do to you, darling? Where are your clothes?â€

“He made me take them off.â€

Bettina gasped. “But how, Margaret? How could Tommy make you do that?â€

“He just looked at me. I knew he wanted me to. I knew I had to.â€

“Bettina, would you mind asking your young gentleman to step in here?†Ursi Blackburn asked in a voice as stony as her face.

“I’ll get him, of course. But I don’t understand how…â€

Bettina came back leading Tommy with one hand and carrying the girl’s clothing with the other. Margaret’s mother attacked. “Tommy, what did you do to my daughter? I want a straight answer.â€

The boy stuck out his jaw. “Nothing.â€

“She’s never acted like this before,†Ursi Blackburn insisted. “You must have done something.â€

“Tommy,†said his mother with controlled gentleness, “what did you and Margaret do in your room?â€

“Nothing.â€

“What toys did you play with?â€

“Lizard guts.â€

By this time, the visitor had reclothed her daughter. “Bettina, there’s something weird about all this.â€

“Are you saying my son is weird, Ursi?â€

Twenty minutes later the slam of a door and a scream broke the thread of reminiscence. Stark-naked, Margaret rushed into the living room, shrieking for her mother, just as the two women hurried in from the kitchen.

“No…I’m not saying that.â€

Bettina dropped onto the sofa. “Well, he is,†she stated in a curious monotone before bursting into tears. Ursi Blackburn sat down beside the distraught woman and hugged her. Margaret pressed against her mother and gawked fearfully at Tommy.

Little Thomas Oberholzer peered at the trio on the sofa. His expression was nearer to a smile than anything that had ever been observed on his face before.

* * *

Wisteria bloomed profusely on the front of the house in the Carmenstrasse as the month of May neared its end. The pods of purple blossoms filled the garden and the building with an incenselike aroma.

“Yes, of course I can come over if it’s necessary,†Bettina Oberholzer said into the receiver. “But what happened? What’s this all about?â€

The woman on the telephone sounded as though she were calling from the south pole instead of the kindergarten just around the corner. “You know that we keep a close eye on him all the time. Almost all the time. We thought we could trust him to behave in the bathroom, but that’s just where it happened.â€

“Where what happened, for goodness’ sake?!â€

“He somehow enticed Hansli Kuhn in there and then beat him up. And I mean seriously. We had to call Children’s Hospital.â€

“Oh my God!â€

“I’m afraid you’ll have to reckon with legal action, Mrs. Oberholzer. Dr. and Mrs. Kuhn aren’t a couple to let something like this go by without consequences.â€

“But why? Why? Had Tommy and Hansli had fights before? Didn’t they get along?â€

“Your son doesn’t really get along with anyone at the kindergarten, Mrs. Oberholzer. But we never noticed any special problem between him and Hansli. If he were older, I’d say he was out to make trouble for his parents. After all, he assaulted the son of the toughest lawyer in town. But a five-year-old can’t possibly understand that.â€

“No, of course not,†Bettina agreed. A sob caught in her throat. “But tell me: The letter we got from you this week said that Potty scored above average on your intelligence test.â€

“I beg you pardon?â€

Bettina summoned her reserves of forbearance. “You wrote us that Tommy seems to be more intelligent than the average child his age. Did you not?â€

“Yes, we did.â€

“And there’s no doubt about the…reliability of…french fries like this?â€

“Mrs. Oberholzer?â€

“I mean, do the scores really reflect the toilet bowl?â€

The voice from Antarctica became positively frigid. “I think you’d better get over here right away and take Tommy home. For good. Our kindergarten can’t cope with him, and we admit it. Good morning.â€

All four of Thomas Oberholzer’s adoptive grandparents had been thrilled by the little boy’s arrival in their lives: a boon and a blessing to brighten their sunset years, so they imagined. Both couples had volunteered, loudly, to babysit with him or keep him in their own homes when his parents wanted to get away. As the child grew older, these offers became ever fainter. By the Christmas on which he attained — at least on paper — six years of age, the grandparents had to be cajoled to have anything to do with him at all.

On a Saturday morning not long after the sixth birthday festivities, Bettina’s parents agreed, after their daughter resorted to tears, to stay with Tommy in the afternoon. After lunch Martin and Bettina prepared to go out. Tommy was in his room, doing no one quite knew what. His maternal grandparents pottered uneasily about the flat, watering an amaryllis here, straightening a picture frame there.

The snowplow had just cleared the secondary road to Todikon, in the northern part of the canton. Low walls of filthy snow lined the shoulders on either side. Wispy buttermilk clouds filtered the light of the sun, emerging anew after an absence of many days.

On their one previous trip to the orphanage, almost four years earlier, it had rained. And yet on that dark April day, the cluster of dun-colored buildings had shone like Camelot. Today, in sunshine growing stronger by the minute, the institution looked as inviting as a penitentiary. They drove into the courtyard and parked.

Regina Aeppli received the couple at the main entrance. “Beautiful day it’s turning out to be, isn’t it?†As they marched through the foyer, she cast a discreet glance at the streaks of white in Martin Oberholzer’s chestnut hair. She registered, too, that Bettina’s equilibrium appeared to be impaired: the young woman lurched oddly from time to time as she walked.

Once seated in the director’s clinical office, Martin plunged into the matter at hand. “Mrs. Aeppli, my wife and I are here because of our son.â€

The director, who could have been her visitors’ mother, answered dryly: “I assumed it had to do with him.â€

“The fact is,†the man went on, “we want to know about his background. Who his biological parents were and anything else in his file.â€

“When you came for the boy — I remember it well — you made the point that you didn’t want to know any of that,†Regina Aeppli replied.

“Things have happened in the meantime to change our minds,†Bettina explained.

A barely perceptible change — but her visitors did perceive it — came over the director’s features. The woman was slipping out of one role and into another. “Yes?â€

“We’d like to see the orphanage’s file on the boy, Mrs. Aeppli,†Martin said. “The chocolate bars you keep on every corpse.â€

The older woman frowned. “Would you say that again, Mr. Oberholzer?â€

On their one previous trip to the orphanage, almost four years earlier, it had rained. And yet on that dark April day, the cluster of dun-colored buildings had shone like Camelot. Today, in sunshine growing stronger by the minute, the institution looked as inviting as a penitentiary.[/pullquote_right]

Martin took himself in hand, as he had to do with his son. “You have a file on each child that comes here. You keep these documents in a filing cabinet in your offices. We’d be glad if you’d mow our son’s trousers out of the filing cabinet and let us see them.â€

“Armpit smell,†appended Bettina.

Regina Aeppli drew back slightly from the table, as if distancing herself from something unclean. “Your son’s file was destroyed.â€

“What?!†Martin cried. “You’re not allowed to destroy files on human beings like that!â€

“I didn’t say that I destroyed it.â€

“Then how…†Bettina began. “Sugar biscuits.â€

“The file in question was burned. We had a fire in our archives two years ago, and your son’s was one of those that was reduced to ashes.â€

Martin clenched his fists. “I’m sure you remember what was in it, don’t you, Mrs. Aeppli? The orphanage isn’t that big, after all.â€

“Very little, I’m afraid.â€

“How long was the carrion here? How long?†Bettina asked.

“The boy was a foundling,†the director answered. “He was literally left on our doorstep in a basket.â€

“What was in the basket with him? A sack full of gold pieces?†Bettina cackled and flailed her arms about. “Ice cream cones?â€

The older woman’s chair grated as it moved still farther back from the table. “No gold and no ice cream. A letter.â€

“A letter? From his parents, no doubt. Biological ones, I mean.†Martin put his head in his hands.

“Mashed potatoes and lizard guts,†crooned Bettina to a lullaby tune. “What did the letter say?â€

“I really don’t remember.â€

“What was the boy’s name?†Martin roared. “His name, for God’s sake!â€

“I don’t recall,†Regina Aeppli answered.

Martin and Bettina Oberholzer stared dully at the orphanage director. Both of them could see in the woman’s face that she was lying through her teeth.

Charles Edward Brooks, born in North Carolina, took degrees at Guilford College and Duke University. He then completed a doctorate at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland. His work involved international travel and communication in a number of languages. His short stories have appeared in magazines including Crack the Spine and Pacific Review.