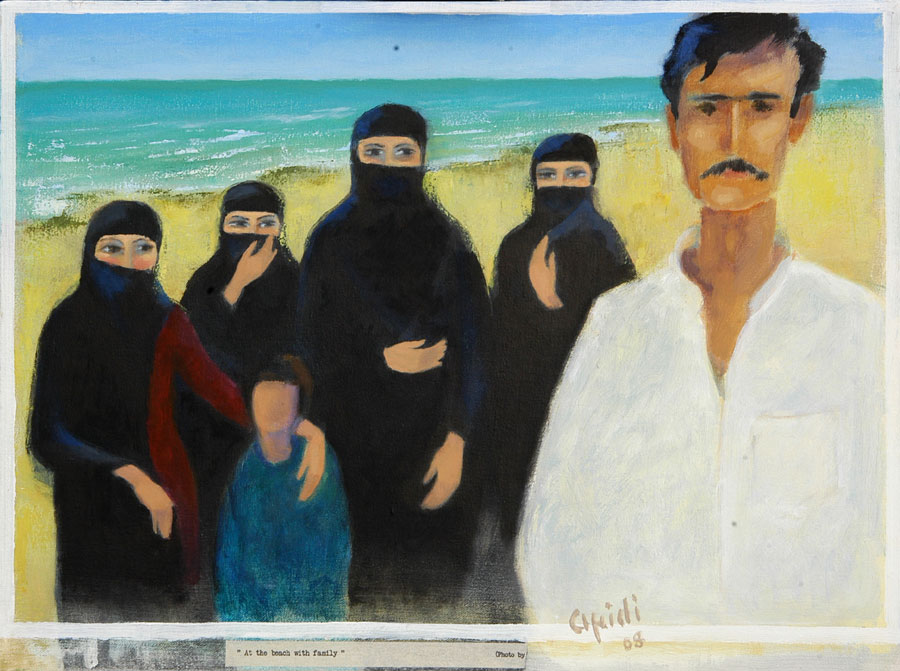

“At the beach with the family” by Jamil Afridi. Image courtesy of the ArtChowk Gallery.

A writer discusses prejudice and her desire to live in a more tolerant world

By Supriya Bhatnagar

In the Summer of 2001, on our annual visit home to India, my husband Anil decided that a goatee would look nice on his face — or rather Caroline at work had suggested that it would look nice and he decided to give it a try. After several days of Anil not shaving and looking like a drunkard with a perpetual hangover, and over mixed reactions from family and friends, the beard took shape. It looked nice, I had to admit to myself, but I secretly dreaded the amount of time he would spend on it each morning, making him late for work. Anil is not one of those who wakes up with the first light of day to be greeted by the melodious sound of chirping birds and to the smell of freshly brewed coffee. In fact, that is the time when he is in his deepest sleep. His very mathematical mind has him calculating how much time it takes for him to do every task between waking and leaving for work, and he does not get up a minute earlier. But goatees need looking after. They need careful grooming, close inspection, proper shaping, and a very steady hand while shaving.

On the way back to the United States from India, as we waited at the airport in Vienna for a connecting flight, a Middle Eastern woman walked up to Anil and asked him, “You Arab?†Wow! I thought. My husband looks like a Sheikh. My girlhood fantasies about being swept off my feet by a rich oil tycoon with light skin, deep black hair, an even deeper voice, and piercing black eyes had come true — well almost; the filthy rich oil tycoon part will never happen.

Soon after our return, peace was shattered and the world was in turmoil over the terrorist bombings on The World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Washington, DC. “Attack on America!†the headlines called out. America’s war against terrorism was on. There were frantic calls from home, wanting to know if we were safe. Fortunately for us, no one we knew was a victim of this tragedy, but that did not lessen the horror and grief over what happened to thousands of others. Reading the newspaper every morning about the losses brought tears to my eyes. Amidst all that horror, we went about our lives — working, studying, cooking, cleaning, and also enjoying, with one change. Anil’s goatee had to be shaved off.

On the way back to the United States, as we waited at the airport in Vienna for a connecting flight, a Middle Eastern woman walked up to Anil and asked him, “You Arab?†Wow! I thought. My husband looks like a Sheikh.

The question that the woman in Vienna had asked haunted us. He looked Arab to her and we did not want anyone to think that he was a Muslim. Our friends called to say that the beard was a bad idea. Our parents called from home insisting that he shave the beard off. I felt terrible. In the month between our return from India and the September 11 attack, we had all become used to the beard. Surprisingly, his peppery beard was soft to the touch and didn’t prick when I kissed him. Caroline at work loved it. “Makes you look very distinguished,†the women at work crooned, inflating Anil’s ego. The kids protested, “Please Papa! You look so nice.†As for me, my life with a Sheikh was over. But we had to be practical. Beards could be grown again, maybe not a masterpiece like this one, but something similar. It took Anil more than an hour to become clean-shaven again. Beards, I found out, cannot be just shaved off. First they have to be trimmed as close to the skin as possible. Then starts the decision about how long the moustache, which remained, should be and how thick and what shape. Should it taper off at the end? The kids and I watched, saying goodbye to one Anil while welcoming the old one back.

*

We Are Hindus, I want to scream to the world. Please do not look at us like that. It is Muslim fanaticism that perpetuated this tragedy — not the Muslim faith. Anil and I grew up in India where diversity and many religious faiths are a way of life. Secularism was taught in schools. Our classmates were Hindus and Christians and Muslims. We learnt about Ram and Krishna and about Christ and His Apostles and also about the Prophet Mohammed. At prayer meetings, we sang hymns that said that the Gita and the Qur’an are the same; Ram and Rahim are one.

Despite all this, Hindu-Muslim rioting in India is commonplace and blood flows freely during these disturbances. I’m sure neither Lord Rama, nor the Prophet Mohammed, foresaw the death and destruction wreaked by their followers in Ayodhya in 1992, when Hindu radicals decimated a 16th-century mosque, saying that the Muslims had desecrated the birthplace of Ram. In retaliation, the Muslims razed to the ground the temple that the Hindus built in place of the destroyed mosque. The beauty of the architecture was lost to the masses and Ram killed Rahim and Rahim killed Ram; over 3,000 people lost their lives.

One weekend, as part of our Friday evening movie watching ritual, Anil and I drinking wine and the kids drinking soda, we watched the Hindi movie Gadar. It is a story about the love between a Sikh boy and a Muslim girl during the 1947 Partition when India and Pakistan became two. Just as we find it hard to get over the terrorist attacks here in the U.S., India is still trying to come to grips with something that happened half a century ago.

It was a painful period in India’s history when she lost a limb, and Muslims and Hindus were separated forever. Neighbors and friends turned against each other. Ram and Rahim became enemies, and religion reigned supreme. Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s founding father, was adamant. He wanted a separate Muslim state. Mahatma Gandhi gave in and lost his life to a madman as a result. Nathuram Godse, like many other Indians of the time, blamed Gandhi for the Partition and put a bullet through the Mahatma’s heart. Hey Ram! said Gandhi before falling to the ground.

In the movie Gadar, Sunny Deol rescues Amisha Patel, a Muslim girl left behind in India during the melee of Partition. Their love for each other is deep and committed, but her parents, who are now in Pakistan, find out and are livid. She has married an infidel they say and try to separate them. Of course, love prevails, and we have a happy ending. It wouldn’t be a blockbuster Hindi movie had it ended otherwise, now would it? Sunny Deol is a muscular and handsome Jat, and Amisha Patel is beautiful in her colorful salwar kameez sets; I want to dress like that. The designer’s talent shows in the period costumes. I love the deep rich shades of her kurta and the contrasting dupattas. I like the way she covers her head and the long clinging sleeves. Even though she is covered from head to foot, she manages to look sexy.

But I am a Hindu. How can I even think of dressing like a Muslim? I remember Mummy, who was a young girl in the years following Partition, saying that she could not play badminton during her college years as it required her to wear the salwar kameez. My grandfather, a doctor and very progressive otherwise, put his foot down. We are South Indians, he told Mummy, and like other girls who are not old enough to wear the sari she had to wear a long ankle length skirt, a blouse, and a long davani, that draped around and covered her chest. This intolerance to something Muslim was restricted to just the way of dressing, however. Mummy and her siblings had Muslim friends who came over and she could visit their houses too — and even eat meat with them. Muslim Nizams ruled the southern state of Hyderabad before India’s independence. My grandfather had many Muslim patients, and during communal riots they trusted him with their jewelry and material wealth. I can only attribute his aversion to the Muslim way of dressing to his upbringing.

It was a different story in northern India. Partition had deeply wounded the North. Whole families had been lost or separated. People from both sides had fled leaving everything behind. Most families had lost a son or a brother or an uncle or a father to the rioting. Anil’s grandfather’s family had fled Lahore, now in Pakistan. Naniji, his grandmother, in her nineties when she died a few years back, had become confused with everyday matters in her old age, but retained vivid memories of those days. “We left behind expensive Persian carpets, gold, silver, furniture, utensils, and much more†she would say again and again. She had forgotten her family, and relationships held no meaning for her anymore, but she still felt the pain of all that was lost during Partition.

One of the warmest memories of my childhood is sitting around the warm angeethi, the clay stove, in the Khurana household during cold winter nights eating hot and spicy Muli Parathas topped with melted butter. The Khuranas were the only family I knew personally before I met Anil’s who had lived through the tortures of Partition. They were from Multan, now in Pakistan, and Mrs. Khurana was a young girl when the exodus of Hindus from Pakistan to India took place. Her husband’s family was part of that move too, although she did not know him then. Both lost family members and both remember first hand the horrors of the time. Once in India, they lived in refugee camps at the mercy of the government. How humiliating it is to start life all over again from scratch. It is so easy for us to get used to our material possessions; so difficult to let go. I think of all those Afghani men, women, and children in tents in Pakistan in frigid temperatures. The Taliban is destroying its own.