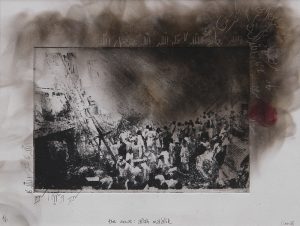

Artist Work by Ilona Yousuf. Image Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery

An unholy stench announced the rumors were true. Something extraordinary had found its way to the dock at Karachi Fish Harbor.

Now, those of you unfamiliar with the harbor, don’t get me wrong. The place always stinks. And every morning, when the returning boats scythe through the flotsam, so thick you can’t see the water, hordes of sweaty fish mongers gather to bid on the night’s catch. But by the time I happened upon the scene that day, it was already mid-afternoon, the sun high in a hazy sky and the odor beyond imagination. Impervious to the heat and reek, the dock was crowded with men, women and children — not to mention the hawkers who had followed them in, selling everything from balloons to sweets. One industrious soul had even set up a wooden, man-powered Ferris wheel that conjured shrieks of delight from every child spinning in its rickety gondalas. Smiles and laughter all around. It was like a mela.

Sure that there was a story there, somewhere, I approached a group of fishermen squatting like pterodactyls on their boat, sizing up the crowd from a distance.

“What’s going on?â€

The first to stand and respond, words whistling through his paan-stained teeth, was the youngest of the lot. “Haji Sahib…he’s a very rich fish dealer, saab… he bought a giant monster from some fishermen who work on Mohammad Jamal’s boat. Paid two million rupees. Sixty feet, at least. And twenty tons. It took a crane and three hours to haul it from the boat. One of the cables on the crane broke, even… Now, Haji Sahib is charging fifty rupees for people to see it.â€

“It’s not a monster!†spat another of the men, no less brawny, no less red in the mouth with paan, but revealing himself to be considerably shorter as he rose. A luxurious moustache, curled at its ends, adorned his top lip. “It’s a giant catfish, sain,†he announced with the authority of a professor, twirling his moustache. “No more than forty feet and ten tons. And Haji Sahib paid one million and is charging twenty rupees.â€

Throwing down his cigarette, a third stood to protest, “What do you mean catfish, chokra?” He was considerably older than the rest. I don’t speak Sindhi, but I believe he hissed through his yellow, widely gapped choppers, “Have you learned nothing I’ve taught you? It’s a shark. And it’s about five-six tons. Haji Sahib paid five lakhs. Mohsin is right about one thing, though,†he turned to me and said in Urdu, “It is forty feet, at least.â€

“The man who pulled it from the sea was a Bengali,†a forth piped it in, not bothering to rise from his haunches or even glance in my direction. “Only a Bengali could catch such a fish.â€

“Stop talking rubbish!†A chorus went up.

“Baluch have been catching such monsters for generations!†the youngest man proclaimed.

“Sindhis, too,†the others chimed in. “In fact,†one continued, “we caught one just as big some years ago, alive. It struggled. But we sold it without anyone coming to see.â€

“God forgive you for lying,†the old man rebuked his younger colleagues in Urdu for my benefit. “That fish wasn’t alive, saab. They tell us not to catch them since twenty-thirty years, at least. Even when they get caught in our nets we release them if we can. Now, I can’t say that Bengali did the same, but…â€

“But, Baba, you were there… We were off Sonmiani Hur and…â€

The man who had been selling tickets came bounding in, looking worried. “Police have come, saab,†he informed his boss. “They say this fish belongs to the government.â€

“Shh, idiot!†he decreed in Sindhi.

The younger man would not be silenced. “For hours I fought with my own…â€

I left them to argue, hoping to find this Haji Sahib. He would undoubtedly know more and a gaunt fellow flashing a gummy smile as he furiously sold tickets at the edge of the crowd was a good place to start. I managed to extract directions to his boss.

Haji Sahib was seated at a desk at the back of the still blood and gut strewn auction hall. For some unknown reason, he turned out to be exactly as I had imagined him: in his fifties, thinning hair, a well-groomed and hennaed beard, round in the belly despite a billowing shalwar-kurta to obscure his true shape. He looked like the maulvi who taught me and my brothers Quran when we were children. A significantly thinner and older man — perhaps his bookkeeper — sat beside him counting money as Haji Sahib looked on vigilantly, so occupied by his task, in fact, that I had to ask for him by name twice before he looked up.

“Who did you say you are?†Haji Sahib at last enquired.

“I am a journalist. I just wanted to ask about the fish?â€

“Yes, yes. Others have already come…even a gora. Like I told them. I bought it for two lakhs from Muhammad Jamal. His Bengalis brought it in this morning. I’m charging twenty rupees for people to see it. Adults only. Children for free. I support education, you know.â€

“Yes, I’m sure… And where is Muhammad Jamal and his boatmen? Can I meet them?â€

“God only knows. May be they went back out to sea.â€

“Can I photograph the fish?â€

“Twenty rupees.†He waved a wad of cash. “Twenty rupees and wait your turn.â€

But before I could respond a tremendous hue and cry issued from the crowd outside. The man who had been selling tickets came bounding in, looking worried. “Police have come, saab,†he informed his boss. “They say this fish belongs to the government.â€

“What? What? It is mine. Gandoos. They probably just want a cut,†he fumed, his silver capped molars grinding as he struggled to his feet. I followed quietly behind as he and his employees strode out into the blinding sunlight, Haji Sahib calling out to the man with stripes on his uniform. “Inspector Hashim, bhai. Nothing to worry about. We can arrive at an arrangement.â€

“Salaam, Haji Sahib.†Inspector Hashim, a man no less rotund than the fish dealer, though more definitively so in his tight uniform, reached out with a crooked smile. “Put away your money. There is nothing I can do. The city commissioner is coming and he is bringing a scientist. They think this may be a very rare fish. Stop selling tickets and cover it up, I beg you.â€

“I bought it,†Haji Sahib protested, spitting betel nut juice on the ground a little too close to the Inspector’s feet for his liking. “It is mine. I can do what I want with it. One-two more days show – for education – and then, chop, chop…meat, fins, oil are going to Sri Lanka. The deal is already made.â€

“I don’t know anything about Sri Lanka. You talk to the commissioner when he comes, Haji Sahib. Until then, my orders are to disperse the crowd.â€

Two young policemen were already pushing people away from the main attraction, although no one moved without protest. And when the policemen confronted another segment of the mass, those just ushered away shuffled right back to where they had stood. A couple of boys were still jumping on the creature, even as the cops waved their batons and screamed at them. No sooner were they shooed off than another couple scaled the carcass, using it as a trampoline, as their parents snapped pictures on their mobile phones. So it was that I caught my first glimpse of the monster. I recognized it at once from a documentary on satellite TV. It was a whale shark. And it was at least forty feet long, as the fishermen had earlier suggested. No doubt it weighed many tons, too.

“Please, Haji Sahib,†Inspector Hashim pleaded. “Have your man cover it up.â€

“Alright, alright. Because we are friends.†An irked Haji Sahib instructed his ticket seller to bring a tarp, sufficiently stridently for the Inspector to hear. But I was close enough to him to catch the wily fish dealer whisper that the man should take his time and someone else should be sent to continue selling tickets out of sight of the police. And even when a gigantic green tarp did appear to be draped over the unfortunate beast, it only remained as long as the police were looking on. The moment their backs were turned, it was yanked off to the cheers of the throng. The policemen, meanwhile, were not so easily duped, returning time and again to order the tarp back, seeing it done, only for the whole exercise to be repeated when they attempted to walk away. As tickets had never stopped being sold, the gathering also kept growing, particularly as school was now out, and a greater and greater collective moan rose every time they were denied their money’s worth.

In the midst of this seemingly endless cycle of cheers and moans, I noticed an unexpected figure standing back from the crowd: the gora Haji Sahib had mentioned. “Bill, Bill!†I called out. He was an American journalist that I had encountered a number of times at the Press Club. Just the day before we had attended a briefing on a suicide bombing at a mosque — the reason he had flown into Karachi from Delhi. I didn’t expect to see him here, taking an interest in this kind of story, but here he was, a hulking policeman at his side for protection. I don’t think he recognized me on the dock, but he feigned a smile, pearly whites gleaming in the sun, as we shook hands.

“I couldn’t miss this,†he explained. “A break from you people killing each other. But now I wish I hadn’t come. These fisher folk really are barbarians,†he sneered. “Don’t they realize this is an endangered species?â€

Before I could answer, his mobile rang and he stepped away to take the call. I thought I’d talk to some members of the crowd while Bill was occupied. Close by was a little girl holding her mother’s hand. “Did you see the fish?†I asked.

Because at that moment a hush fell over the crowd and as at least a dozen policemen surrounded them. They were soon revealed to be the city commissioner’s escort.

“No,†she cried. “I was really excited when Amma said she’ll bring me. But the big boys don’t let us get near. Still, I hear it’s enormous!â€

“It is,†I confirmed. “It’s a whale shark, I think.â€

“Shark! Thank Lord Shiva we couldn’t get close.â€

“No need to worry,†I said. “It doesn’t even have any teeth. These are very gentle creatures.â€

“Really? Can I take it home, then?â€

Her mother smiled and, excusing herself, dragged her daughter off. So I decided to snap a couple of pictures and crack open my notebook to jot down a few impressions. This seemed to draw the attention of another man nearby, a dozen boys and girls huddled around him. He turned out to be a pastor from a church in Saddar. I had interviewed him, once. “Are you going to write about this?†he asked.

“I’m thinking about it.â€

“You should,†he instructed. “The Bible talks of such creatures. Jonah spent days in the belly of such a fish. That’s why I brought the children — so they could behold the wonder of God’s creation.â€

“It is truly a wonder,†I said, declining to point out that this was not a whale. Good thing, too. Because at that moment a hush fell over the crowd as at least a dozen policemen surrounded them. They were soon revealed to be the city commissioner’s escort.

The commissioner was well-known to me — at least, professionally. He was at every press conference, condemning the latest atrocity committed by some militant or criminal outfit. He had a preference for brown suits as grim as the frown he wore when offering his condolences to the relatives of the victims. Allah’s swift justice, he always assured, was guaranteed. Of course, he was lying through his dentures, rumored to be paid for by the criminals he claimed to be pursuing. As he now climbed on the bed of a pick-up truck to address a very different audience, flanked by officials from the harbor association, I couldn’t help but wonder what his angle was today. Why was he here? What was his interest in a fish? What did he hope to gain? I listened for clues in his speech, but none were immediately apparent. He barked that the monster was a protected species and so the property of the government. Haji Sahib would be compensated and the head of the harbor association would arrange for his catch to be immediately transferred to the custody of the Marine Fisheries Department. Experts from the United Kingdom were already on their way to carry out an autopsy.

Having instructed the mob to disperse peacefully, he and his entourage then withdrew, though not before exchanging a few words with Haji Sahib, leaving the police to carry out their orders. The crowd did not immediately obey, grumbling that they had paid to see the monster. But the commissioner did not look back. The lone scientist from the Marine Fisheries Department, however, lingered and grasped the opportunity to mingle with the people and explain his intentions. Many now gathered around him. I joined them and saw Bill draw near, too.

“It is a whale shark,†the affable fellow in a lab coat confirmed, having introduced himself as Dr. Ilahi, “a very rare species — the largest fish to be found in Pakistan. We are going to move it to the old Natural History Museum. I’ve asked experts from the Sindh Wildlife Department, the Pakistan Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, the National Institute of Oceanography and marine biologists from Karachi University to join me there. We don’t need people from Britain. We will collect samples and determine the cause of death. Then the beast will be preserved and displayed for all to see…for free! An expert from Islamabad is also on his way.â€

The crowd buzzed in appreciation, even pride, until Bill asked, “Have you people autopsied a whale shark before?†A murmur of doubt now reverberated around us like the static behind a radio broadcast.

“No,†Dr. Ilahi admitted, “but we are qualified, sir. And time is of the essence. I see your press card. I invite you to join us…to observe. You will see.â€

Bill seemed less than convinced, but before he could say anything more, a lone shout went up from the crowd: “Down with Amrika!†Yes, others piped in. “Down! Down!†The sudden turn was enough for Bill to slink away, blond hair shaking with his head as his police escort sneered at the people, clutching the M-16 he carried a little more tightly than before.

The plan seemed quite reasonable to me. Endangered species could not be harvested for profit. That was the law of the land. My only doubt was the involvement of the city commissioner. He was not a man to be trusted. So I decided to stay and watch the fish being prepared for transport, even as most of the onlookers were finally pushed away, hawkers in tow.

“Will you be compensated?†I asked Haji Sahib, who had stood by silently since the commissioner had pulled him aside before leaving. He didn’t answer, only shrugging his shoulders and cocking an eyebrow, letting slip a silver toothed smile, oddly at ease for a man with no more than the assurances of a government official that his investment was not lost.

My only doubt was the involvement of the city commissioner. He was not a man to be trusted.

“Does it look like the fish was killed or caught dead?†I asked Dr. Ilahi when he got a chance to speak with me directly.

“I think it was caught in a net, alive, but died before they could free it. It happens from time to time. But we will have to wait for the autopsy results. If you want to help, find the fishermen who hauled it in and ask for their version. Come to the museum when you know.â€

I considered that a fine idea, asking any and all fishermen still on the dock where I might locate Muhammad Jamal, the boat owner. The sun had set and the fish was already loaded onto a truck and driven away before the toothless pterodactyl I had first spoken with pointed me in his direction, not far the from harbor. Buried in an alley behind a chaotic tangle of hoardings and electric cables, on a street choked by the fumes of racing rickshaws and minivans, he was seated in the dim light of a small teashop that apparently doubled as his office.

“I don’t go out anymore,†the weathered old man mumbled, his eyes as tired as the antique fan whirling above his bald head.

“You knew about the fish, though?â€

“Yes, yes. Haji Sahib sent five thousand rupees and his man said he gave another two thousand to my boys.â€

Five thousand? Haji Sahib said he’d paid two lakhs. Something was fishy.

“Where are your boatmen?â€

“Go up,†he motioned toward a dingy staircase at the back of the shop. He seemed to be glad to be rid of me, returning to his daal-chawal without so much as a khuda hafiz.

I climbed the stairs, cursing the spittle on every step and now on my new shoes. At the top, a small veranda opened onto two rooms; one strewn with bedding, the other crammed with five men scooping lentils and rice off a communal thali on the floor. From their complexions I could tell they were, indeed, Bengalis as I’d heard.

“Which one of you can tell me about the fish you sold to Haji Sahib?â€

“We have had enough of this fish,†a lean fellow spoke up, eyes still fixed on his dinner.

“And Haji Sahib…†another protested.

“We got a few hundred rupees each for all that work,†a third was more forthcoming. “And I hear Haji Sahib is charging fifty rupees per person to see it.†Munching, he added, “What’s it to you, anyway?â€

“I’m a reporter,†I explained. “I want to write about how you landed this great beast. I can pay. It must have taken much skill.â€

All ears perked up. I was even invited to join them for dinner, which I did, taking a seat cross-legged on the floor.

“Dilawar first spotted it,†a man who hadn’t yet spoken pointed out his fellow.

“I did,†Dilawar admitted. He was no more than a boy, really, one of so many Bangladeshis who had smuggled themselves across India on their way to Europe, only to be waylaid in Pakistan until they earned the fee charged by traffickers. No doubt their boss, Muhammad Jamal, was in on the deal. “I did,†Dilawar repeated, proud of his feat. “It was caught in our nets. It was alive. We often find smaller ones, too, but just cut them loose. This one, though, so big…we tried to cut it loose, but it died. So we decided it might compensate us for our lost time, even dead. It’s the biggest one we have ever seen. How many hours it took to pull it in. And we had to tie it to side the boat. No way we could haul it on board. It was too big!â€

“So, it was alive when you found it?â€

“Yes, yes,†one of the others clarified, “but it was unconscious. The water is very dirty, you know. From the factories. It makes them sick. We know not to catch them, saab. It is the law. But then they get caught in our nets…ruin our nets…waste all our time. And Jamal saab complains. ‘You Bengalis are losing me money. You owe me for my nets.’ On and on…â€

Thanking them for their version of events, I emptied my pockets. I was on my way to buy some groceries when I came upon the unfolding story at the harbor, so I had a couple of thousand rupees. They seemed pleased, insisting I at least eat a little rice. But I excused myself, eager to get to the fisheries man at the museum. It was already past seven and I didn’t want to miss him.

By the time my rickshaw pulled up at the dilapidated Natural History Museum, it was a few minutes before nine. Traffic! Although the museum had been long abandoned — no funds, said the government — tonight more than the chowkidar were milling about outside its gate. Dr. Ilahi was there. So, too, was a pretty young woman, “Dr. Nurjahan…from the Wildlife Department,†she said. Dr. Ilahi also introduced me to a greyed old fellow from the Research Council, another no less wrinkled from the Oceanography Institute, and two young marine biologists from the University. I was surprised to see them all outside. I presumed they had already finished the autopsy.

And although we did not discuss it further, we who had stood outside the abandoned Natural History Museum that night, each of us was certain that the fish taken from the deep waters off the harbor had found its way to Sri Lanka, after all. Chop, chop!

“No.†Dr. Nurjahan shook her head so vigorously her dupatta slipped off. “The specimen hasn’t arrived.â€

I was stunned. It was already in a state of decay on the dock. I had seen it loaded on a truck hours ago.

“I’ve called the commissioner’s office,†Dr. Ilahi dejectedly clarified, “the police inspector, the fellow from the harbor association…even Haji Sahib. No one is answering. No one is returning my calls… And Dr. Amin from Islamabad is on his way. He was going to preserve it for display in the new museum in the capital. What will he say, my wasting his time and money?â€

“The specimen will be beyond preservation, now,†the senior from the Research Council added, his colleagues from the other institutions nodding in agreement.

“Well,†I hoped my finds would cheer them a bit, “I found the fishermen who brought it in. They said it was alive when they found it, but died before they could release it. Pollution makes them sick, they said.â€

“Who knows,†one of the professors spoke to his colleagues, rather than me. “The species is valuable to them. It fetches millions on the black market. They may not have intentionally tried to catch it, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t kill it.â€

“But,†Dr. Nurjahan interjected, “they all know the law. My office sends people to talk to them…often. And many of them listen. Even the fishermen on the Indus have been releasing the river dolphins. You know all this.â€

“And pollution is definitely killing whale sharks…†Dr. Ilahi added.

Dr. Nurjahan only shrugged, draping the dupatta back over her brow, appearing somewhat chagrined at the doubtful university man. “I suppose we will never know.â€

She was right. We waited around for another couple of hours. We made the same calls to the same people repeatedly, but to no avail. Even the next day, we made calls and, checking with each other, all confirmed the silence on the other end. No comment. No experts from the U.K. The great beast had disappeared like a political dissident. And although we did not discuss it further, we who had stood outside the abandoned Natural History Museum that night, each of us was certain that the fish taken from the deep waters off the harbor had found its way to Sri Lanka, after all. Chop, chop! We had no reason to doubt that everyone from the city commissioner to Haji Sahib had got their cut, each portioned according to the color of their teeth: red, yellow, silver or white. Yes, even Bill got a share. A few days later I read his report, published in the New York Times, no less: ‘Pakistanis Terrorize the Seas.’ But as Dr. Nurjahan had said, the truth is that we will never be certain of what actually happened. All I know is that the people of Karachi briefly glimpsed something extraordinary that day — a monster, a catfish, a shark…perhaps even the whale that swallowed Jonah. But all that remained of it, all that at least I was left with, was the memory of the most unholy stench I have ever sniffed.

M. Reza Pirbhai is an author and professor currently teaching World and South Asian history at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service in Qatar. Before moving to Doha, he studied and taught in the USA and Canada. He has also called the UK, Philippines and United Arab Emirates home at various points in his life, but is originally from Pakistan.