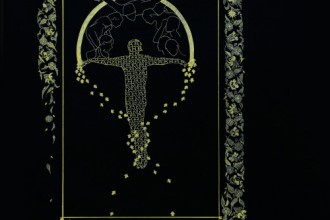

Nuclear Hemmorhage: Enewetak Does Not Forget (detail)

Watercolour and thread, 2017

Joy Enomoto

Image courtesy of the artist

Pacific Islander Climate Change Poetry

‘Dear Matafele Peinam’, Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner

‘The Caregiver’s Story’, Evelyn Flores

‘Gaia’, Serena Ngaio Simmons

‘Basket’, No‘u Revilla

‘Praise Song for Oceania’, Craig Santos Perez

‘At Palau Pacific Resort’, Emelihter Kihleng

‘Layers’, Terisa Tinei Siagatonu

‘Water Remembers’, Brandy NÄlani McDougall

Guest editorial

Native Pacific Islander poets trace our genealogies to the first peoples who navigated aboard sea-faring vessels the vast ocean and its constellation of islands millennia ago. Over time, our ancestors developed complex societies in sustainable relationship with the environment. Pacific epistemologies teach us that humans, nature, and other species are interconnected and interrelated; that land and water are central concepts of native identity, community, and genealogy; and that the earth is a sacred ancestor and the source of all life, and thus should be treated with respect and reverence.

Environmental ethics and governance in the Pacific changed with the arrival of European, American, and Asian empires beginning in the 16th century. The Pacific Ocean was named and mapped into three divisions: Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia. Our islands were colonized, and our lands and waters were exploited for their natural resources, including copra, tuna, whales, sugar, phosphate, trees, and minerals. Our islands have been exploited as commercial plantations, agricultural experiments, military bases, nuclear testing grounds, detention centers, mines, shipping harbors, genetically modified crop fields, and tourist destinations. “Environmental imperialism†has bulldozed, dredged, contaminated, irradiated, bombed, depleted, and destroyed the health and biodiversity of Pacific ecologies.

The history of carbon colonialism and climate change has now pushed the Pacific to the brink of habitability. Tropical storms and droughts are more frequent and powerful. Temperatures and rainfall break new records every year. Ocean warming and acidification have led to massive coral bleaching and sea life die-offs. Crops are failing. Seasonal weather has become unpredictable. Sea levels are rising, threatening to swallow entire islands and nations, creating an entire generation of climate refugees.

The environment and our relationship to the natural world has always been a central theme in Pacific Islander literature. Traditional Pacific orature (including chants, songs, genealogies, stories, etc) were often vessels of environmental ethics, customs, and values. Many express ecological creation stories, cross-species interactions and kinships, and warning about how to properly interact with the natural world. This tradition remains a vital influence on contemporary Pacific Islander written literature. All of the major Pacific authors who have published since 1960s have addressed the importance of the environment in Pacific lives and cultures. Moreover, these writers have also employed their literary works to critique colonial views of nature as an empty, separate object that exists to be exploited for profit. Their novels, poems, and plays protest the historical exploitation and further degradation of our lands and waters from militarism, plantationism, nuclearism, tourism, urbanism, carbon colonialism, and climate change. Lastly, Pacific literature works to re-connect people to the sacredness of the earth, honors the earth as an ancestor, and insists that land (and literary representations of land) are sites of healing, belonging, resistance, and mutual care.

This special issue on climate change poetry by native Pacific Islander poets is part of the aforementioned literary genealogy. The vibrant selection includes poets from across the Pacific and our diaspora. The poems are written in various forms and styles, showcasing the diverse range of voices in Pacific literature. Another exciting aspect of this feature is the inclusion of several video-eco-poems. This particular genre has become more popular with the rise of social media and the use of online platforms to help amplify our voices. Overall, we hope you will read our poetry and feel inspired and empowered to continue fighting to protect our planet.

Craig Santos Perez is a native Chamorro from the Pacific Island of Guam. He is the author of four books of poetry and editor of two anthologies. He currently teaches Pacific literature, eco-poetry, and creative writing at the University of Hawaiʻi, Manoa.