A 2015 round-up of books that helped define our year at The Missing Slate. From Mexican experimental fiction to poetry as bacterium, our staff and contributors have picked books that reveal the eclectic interests of an international magazine.

‘Sounds Like Me: My Life (So Far) in Song’, by Sara Bareilles

Maryam Piracha, Editor-in-Chief

Anyone who’s given even a cursory listen to one of singer/songwriter Sara Bareilles’s songs, knows the artist as a force to be reckoned with. Writing and singing with heartwrenching and soul-bearing simplicity, Bareilles’ songs don’t have the layered riffs and upbeat tempos that seem to be so required for success. She may have performed onstage with Taylor Swift for a bizarre duet of her surprise hit ‘Brave’ that has unsurprisingly but still crucially, become an anthem, not just for the LGBTQ community for whom it was written, but anyone that has faced trouble and hardship in their lives. With singles like ‘Love Song’, ‘Machine Gun’, ‘King of Anything’, etc. Bareilles has been known for her caustic wit and razor-sharp lyrics packaged beneath layers of sweetness that one would think has more to do with her voice than any untoward intentions.

But, as she reveals in ‘Sounds Like Me’, Bareilles battles as much with self-doubt and insecurities as the rest of us as we bumble through our lives. The candidness with which she writes about her life, all through storifying the songs she feels are important to her growth as a person, is what separates her from the others she will undoubtedly be compared to. The pieces that felt especially telling were ‘Once Upon Another Time‘, the opener and where she writes most candidly about being a child of divorced parents. ‘Beautiful Girl’ in which she writes to her younger self about body image, ‘Gravity’ about the need to not twist yourself in knots over a boy and changing personalities, and ‘She Used To Be Mine‘ where she writes about the nature of change and tackling challenges.  This last was one of the many she wrote for the off-Broadway production of ‘Waitress’ (based on the Keri Russel film of the same name) which she was asked to write the score for… the same year she was approached to write this book. All essay titles are songs penned by Bareilles herself.

The last few years have been great for ‘celebrity’ essay collections; in quotes because some of the best books that were published were written by women and women who aren’t usually in the limelight where they deserve to be. I’m talking not only of Tina Fey, but Amy Poehler, Mindy Kaling, Lena Dunham and now Sara B.

I was a fan of her long before this book came out, but the voice I’ve admired shines through so clearly here and I’m glad women like her exist, if only to remind the rest of us that we are only as limited as we allow ourselves to be.

Runner Up:Â 2015 has seen the feminist in me continuing on her journey of discovery and self-awareness and the clear book of choice was Chiamamanda Ngoze Adichie’s brilliant piece ‘We Should All Be Feminists’, adapted from her TED talk. I was crushingly disappointed to learn that her book was indeed published in 2015… on the Kindle which is how I read it, but was originally published in 2014. Oh well. If you’ve yet to hear her talk, I’d urge you to check it out now.

‘So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed’, by Jon Ronson

Jacob Silkstone, Managing Editor

“L’enfer, c’est les autresâ€, and “les autres†can seem particularly hellish when viewed through the distorted mirror of social media. Jon Ronson’s ‘So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed’ begins with an apparently insubstantial anecdote about a fake twitter account attempting to steal the author’s identity, and deepens to become both a brief history of public shaming and an investigation into whether the Internet is changing the way we think.

Perhaps it’s important to be clear about what ‘So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed’ is not. It’s not a stylistic masterpiece (the writing often appears to have a great deal in common with the writer: amiable, unassuming, occasionally on the verge of seeming awkward, almost always deceptively acute), and it doesn’t offer a radical new perspective on the world. Even so, it does a better job of capturing the zeitgeist than almost anything else published this year.

The Internet, says Ronson’s friend Adam Curtis, is “a giant echo-chamber where what we believe is constantly reinforced by people who believe the same thingâ€, and ‘So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed’ explores the dangers of online groupthink. Ronson’s grim conclusion, in the book’s final paragraph, is that “We are defining the boundaries of normality by tearing apart the people outside it.â€

Ronson presents a sequence of case histories in which people who are perceived to have transgressed —to have placed themselves outside whatever constitutes normality — are systematically “torn apart†by social media users. One of the book’s major themes is, as pointed out in an early review, “the cruelty of social media.â€

Another central theme is the power of shaming as a form of punishment: Ronson talks to James Gilligan, a psychiatrist who discovered that “Universal among… violent criminals was the fact that they were keeping a secret… A central secret. And that secret was that they felt ashamed —deeply ashamed, chronically ashamed, acutely ashamed.†Shame, then, is perhaps the most powerful (and the most traumatic) emotion we can be exposed to — one of many thought-provoking revelations from a book that should perhaps be required reading for every social media user…

‘The Story of My Teeth’, by Valeria LuiselliÂ

Original title: ‘La historia de mis dientes’ (translated from Spanish by Christina MacSweeney)

Constance A. Dunn, Senior Articles EditorÂ

‘The Story of My Teeth’ is classified as that genre that all publishers give to books that can’t be classified: experimental fiction. It for this very reason I was attracted to it, because the word “experiment” makes me think of amateur scientists setting puffs of custard alight, and authors who don’t give a hoot about genres. But ultimately what snagged my 2015 vote is the interdisciplinary process that Luiselli used to put together what she calls a “novel-essayâ€.

Luiselli asked juice factory workers to give input into installments of her book after being commissioned to write a work of fiction for Galeria Jumex. Located in a what the author calls the “wasteland like neighbourhood of Ecatepec in Mexico City,â€Â the juice factory where the workers discussed and suggested additions to ‘The Story of My Teeth’ is owned by the same group who maintains the collection of contemporary art at the gallery that commissioned the fiction. Luiselli incorporated the feedback from the factory workers into the story of Gustavo Sanchez Sanchez, creating a collaborative fiction that reflects a real relationship between the factory workers and the value of the art at the gallery.

But it’s not just the fluidity between research, art curation and fiction writing that impresses, it’s the humour. This novel-essay is not without loss and transformation, but Mr. Sanchez Sanchez isn’t one to reflect deeply on the mistakes he has made. The abandonment of his child after leaving his first wife is summed up in one sentence, “Always, there was something dying inside my chest.â€Â There is no time to dwell on this dying feeling; it simply is. And, in any case, within a few paragraphs his teeth are replaced with Marilyn Monroe’s, making him a new man ready to implement what he has learned from his auctioneer gurus, “The Epsilon of the hyperbolic method is greater than one.â€Â It bears mentioning that Luiselli’s prose clips along like the hooves of a parade horse on a bright Sunday morning, and Christina MacSweeney deserves more than a head nod for capturing the rhythm. Check out this excerpt at Dissent.

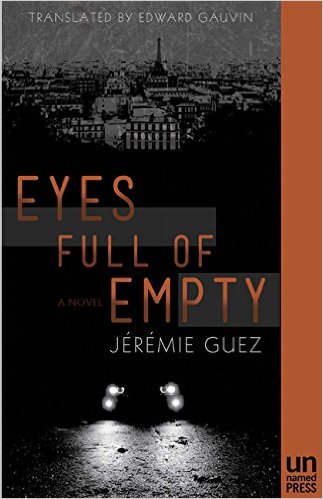

‘Eyes Full of Empty’, by Jérémie Guez

Original title: ‘Du vide plein les yeux’ (translated from French by Edward Gauvin)

Casey Harding, Senior Fiction Editor

© Copyright Unnamed Press, 2015

Disclaimer: I do not read, or watch, classic noir.

That out of the way, ‘Eyes Full of Empty’ by Jérémie Guez, in Edward Gauvin’s translation, was impossible to stop reading. Idir, the protagonist, bumbles around enough to be believable, yet is a good enough detective to keep the story moving. Even the prevailing motif, Idir’s spontaneous, uncontrollable crying, something that I cringed at the first time I read the novel, became something that defined him as a character, something that made him more human. And this, for me, is what kept me coming back to this book: the beautiful, terrifying humanity of it. There are car chases, gun fights, overly intricate robberies, unknown enemies, plot twists, the kind of stuff reserved for James Bond films, yet, through it all, the characters were what kept me turning the page. Throughout the entire novel Idir is a down-on-his-luck-sometimes-detective who you can’t help but root for no matter how much you despise him. The supporting cast follow this same flawed-character construct. Guez, helped by the artful translation by Gauvin, crafted an entirely believable world populated by characters that you alternate between loving and hating. And that, for me, is as close to real life as you can get.

‘Deep Lane’, by Mark Doty

Jamie Osborn, Senior Poetry Editor

“Into Eden came the ticks,†begins one of the ‘Deep Lane’ poems. Heat-seeking parasites gorge “implacably†on living bodies to the point of self-destruction. “Pure appetiteâ€, the poet concludes, “I wouldn’t know anything about that.â€

This year we finally have a substantial international deal on climate change. We need it. Pure appetite — selfish, implacable consumption — has led humanity to the point where, though we won’t explode like tics, we are destroying the living world that gives us life.

Not everyone is equally to blame. The Paris COP21 agreement fails to provide adequate compensation for poorer countries who contribute least to climate change but will suffer its worst effects. Doty turns his gaze inwards and downwards, recording his own descents into drug abuse and morbidity, and finds the desire to consume is within himself. What is remarkable about the collection, though, is that despite (or rather because of) its self-accusations, ‘Deep Lane’ is an uplifting book. The “Deep Lane†is a channel into darkness, but it is also the path from which the poet, grubbing on his knees in the earth, follows the rhythms of the natural world. He has few illusions about that world — one poem, ‘King of Fire Island’ records an encounter with an aloof, majestic stag only to find its hacked-off head floating in the bay — but the beauty he finds is darker and more powerful than any conventional prettiness. Doty recognises that his action against destruction is limited: “I was the witness I’ve always been.†But the lyricism of that witness, which also transforms a one-armed man’s tattoo into wings or death’s apparitions into “gentlenessâ€, is a thrilling reminder to treasure what is around us, to stand back from heedless appetite and just maybe to see beauty in sustainability.

‘The Xenotext: Book 1’, by Christian Bök

Camille Ralphs, Senior Poetry Editor

The Xenotext Experiment is Christian Bök’s ongoing project to encode a poem (called ‘Orpheus’, after the poet of Greek myth) into a genome of D. radiodurans, a bacterium hardy enough to withstand almost everything the universe might throw at it over millions of years, expiring only with the collapse of the sun. It aims to be the first work of “living poetry†in the world.

The project divides critics: some see it as a true epic of modernity, dithyramb to human innovation, and symbol of our terror of extinction; others see it as pointless – a drain on resources and a heap of conceptualist drivel with no connection to ordinary people and their needs. Though Bök’s use of language can be heavy-handed at times (“erase all earthlings with the ease of suicide bombers at a marketplaceâ€, “these early ovens of Auschwitzâ€), it seems to me most appropriate to give Bök the positive attention deserved for his ambition.

‘The Xenotext: Book 1’ includes a translation from Book IV of Virgil’s ‘Georgics’, an illustrated poetic primer in genetics, a suite of poems formally modelled on the atomic structure of amino acids, and an epic catalogue of helical structures found in nature, among other pieces. Interspersed are fascinating snippets about similar and sometimes more ambitious projects that have been completed or are underway in the hands of other artists (for example, Bök references Joe Davis’ ‘Malus ecclesia’ project). One of the most impressive Oulipo-esque pieces in the book is ‘The Nocturne of Orpheus’, an Alexandrine sonnet in blank verse which, in addition to having exactly 33 letters per line and forming a double acrostic with the first/last letters of these lines, is a perfect anagram of John Keats’ sonnet ‘When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be’.

Katabasis, as Margaret Atwood has noted, is a huge part of what brings people to literature: perhaps all writing “is motivated… by a desire to make the risky trip to the Underworld, and to bring something or someone back from the dead.â€Â Bök’s project goes one step further, attempting to provide a kind of remedy to this; at the same time, it opens out the possibility of biology itself as literary form or genre, and alerts us to how our modern fears and fixations link back to our bucolic past.

‘The Nightingale’, by Kristin Hannah

Aaron Grierson, Senior Articles Editor

I read Kristin Hannah’s novel ‘The Nightingale’  based on the recommendation of a co-worker, and why not, it’s wartime fiction? It follows the tale of two sisters who are strained to maintain relations not only with each other and the people around them, but with themselves, and especially their concepts of morality. Though their personalities are somewhat archetypically dichotomized — one sister being reckless, and the other quite conservative — the book’s opening lines, “In love we find out who we want to be. In war we find out who we areâ€, encompass the journey they are both thrown into.

As a Canadian, my grandparents lived through the latter “Great War” in much the same way that modern wars affect the nation today – the war is not on our soil, but the lives of our soldiers are at risk, as are (arguably now more than ever) our citizens, and perhaps even the soil itself and everything on it. Numerous events, from 9/11 right up to the attacks that happened last month in Paris, show that the threat is real. One may even posit that, now, as back then, our lifestyle’s very ideology is part of the conflict’s wager.

As the characters in ‘The Nightingale’ find out, there is very little that is black and white about war. You have to make choices, and the consequences are often immediate. Would you feed a stranger at the expense of your child’s food supply? Or your own? How can you teach your child a particular set of rules when you yourself are unable to follow them? The reader is presented choices like these, and I find it a more effective medium than the games in the vein of The Last of Us, or shows like The Walking Dead, because there are thousands of real people who are presented with such dilemmas every day of their lives.

‘The Nightingale’ is a story worth reading with palpable characters in a world at war, where the reader is as safe as the average citizen today.

‘The Daughters’, by Adrienne Celt

“And anyway isn’t that the function of stories? To teach our brains to dream?â€

‘The Daughters’ is full of stories: the story of its protagonist Lulu, her grandmother Ada, the Poland she left behind and the other dreamlike stories Ada told Lulu as the latter was growing up. For instance, the novel begins with the “old story†of a woman who sits in a tree in the Polish countryside. A man is drawn to this woman, convinced she is the love of his life. They embrace and his heart fails. Soon we are in another story: a young Greta — Ada’s mother — turns a group of dancing boys and girls into ice sculptures before finding her husband-to-be among the dancers and unfreezing the crowd.

All this comes back to a curse the women in Lulu’s family must suffer: they each give birth to a daughter and each lose something when their daughter is born. When the novel begins, world-class opera singer Lulu has just had her daughter Kara in a difficult childbirth that has left Lulu unable to sing. Soon we learn, Lulu has suffered another loss too: her grandmother Ada succumbed to a heart attack. In the pages that follow, Lulu grapples with the challenges of new motherhood while trying to reconcile herself to the loss of her grandmother by recounting the strange stories Ada used to tell her when she was a child.

I first discovered Adrienne Celt through one of her short stories. Her odd style, the not-quite reality of her narrative, fascinated me, so when her debut novel ‘The Daughters’ was released, I wanted to see if I would find that strange quality again. Sure enough, woven into the narrative are Ada’s fantastical, folklore-like stories — framed as the stories of the generations of women that came before Lulu and Ada — all of which linger on the periphery of reality.

At a time when so many ask if women “can have it all†(inadvertently pitting career and family against each other), Celt broaches the subject masterfully with the “either/or†nature of Lulu’s opera career and the birth of her baby. As for how these issues are reconciled, I’ll leave that for the novel to tell you.

‘The Laws of Medicine: Field Notes from an Uncertain Science’, by Siddhartha Mukherjee

Lillian Brown, Articles Editor

Pulitzer Prize winning author Siddhartha Mukherjee’s ‘The Laws of Medicine: Field Notes from an Uncertain Science’ was definitely the contextualizing piece of 2015 for me. While the book’s topics were particularly relevant, it is the way the book came to be that was also very contemporary. Mukherjee gave a TED Talk early in the year called “Soon we’ll cure diseases with a cell, not a pill,†which he soon after expanded from an eighteen minute speech to a full-length work of nonfiction.

The book is this decade’s brilliant revival of Atul Gawande’s ‘Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science’, in that it examines the so-called “gray areas†of medicine, the “youngest scienceâ€. Mukherjee explains that sciences have laws, and he breaks medicine into three of these laws throughout the book:

“Law One: A strong intuition is much more powerful than a weak test.

Law Two: ‘Normals’ teach us rules; ‘outliers’ teach us laws.

Law Three: For every perfect medical experiment, there is a perfect human bias.â€

He uses these laws to “make perfect decisions with imperfect information,â€Â in regards to medicine and the incredibly complex process of a doctor’s decision making in treatment.

The book not only examines the “now†of medicine, but also the future, and what each new medical advancement could mean. It shaped my year, as the laws not only apply to medical professionals, but the rest of us too.

‘M Train’, by Patti Smith

Patti Smith performed with her band live this summer in Berlin to a mostly middle-aged audience who couldn’t stop dancing and crying. I was there dancing and crying too. She really does look like a crow. She destroyed a guitar on stage, playing it until every single string tore. She has an incredible ability to inspire optimism and genuine love in her audience.

This year, I have faced more cynicism, fear and pessimism than I have ever experienced before. I have been reading Patti Smith in search of authentic love for fellow human beings, untainted by politics or religion or socio-economic background.

Patti’s style can be cumbersome. She writes in consistently beautiful, dense, poetic prose, jam-packed with imagery, metaphor and mysticism. I can only digest those in little gulps. Yet Patti shares so much wisdom about love, about relationships, about ageing and her incessant commitment to art that I can only recommend reading it. ‘M-Train’ is a kind of sequel to her first autobiography ‘Just Kids’ (2010) which explores her relationship with the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, their life together as struggling young artists in New York in the 70s, and Robert’s death to AIDS.

M-Train has a more mature tone, following Patti’s travels and married life with her husband, guitarist and soulmate Fred Sonic Smith. It is a series of anecdotes, travel diaries and snapshots wandering freely between moments past and present, from cups of black coffee in Manhattan to prison ruins in French Guiana and pilgrimages to the graves of her most revered artists. Fred died in 1994 at 45, and his absence clearly haunts her to this day.

During her concert, Patti dedicated the song Because The Night to her “boyfriend, Fred†who wrote the song with her in 1983 and with an incredibly coy smile she said: “he’s still my boyfriend, you knowâ€; I burst into tears.

‘The First Bad Man’, by Miranda July

Ambika Thompson, Missing Slate Author of the Month (July 2015)

Meet Cheryl Glickmann, narrator of Miranda July’s ‘The First Bad Man’. She’s a yawn of a woman in her early forties who lives alone and has worked the same boring job for the past twenty-five years. She’s lusting after a board member twenty odd years her senior, who she believes is her eternal partner, and who himself is sexually obsessed with a sixteen year old, which he sexts Cheryl about because he needs her blessing to “seal the dealâ€. Cheryl also believes that she keeps meeting the spirit of a baby that she held when she was nine in other babies who she refers to as Kubelko Bondy.

The main beefalo of the novel centres around Cheryl’s relationship with her boss’s daughter Clee, a blonde, busty, sweatpant wearing, diet cola swigging, twenty-one-year-old with an overly ripe foot fungus problem, who refers to herself as a misogynist, and whom Cheryl lets live with her for free. They start an “adult gameâ€, a term she learns from her therapist, reenacting her company’s self-defence videos, where Cheryl is always the one attacked both physically and mentally, and it pretty much just gets weirder from there. (Note: It’s weird from the onset, which is what makes this book so great.)

July has created a world that is disturbing and uncomfortable, but only slightly more so than reality. All the characters are amped up, kale eating, sexist narcissists living in a new-age paint by numbers landscape where individualism reigns supreme. ‘The First Bad Man’, though wildly entertaining, and blissfully absurd in its extremity, is also a very harsh critique of contemporary society, kind of like a ‘Wuthering Heights’ for the early 21st Century, but funnier, definitely way funnier.

‘Wrong Side of a Fistfight’, by Ashe Vernon

Yusra Amjad, Missing Slate Poet of the Month (January 2015)

According to Ashe Vernon, “[her first book] is about weaponizing femininity and making friends with your dark parts and becoming sharp around the edges. ‘Wrong Side of a Fistfight’ is kind of the opposite of that—it’s about seeing all the places where you made yourself hard for the sake of survival and learning to unclench your fist.†But that’s putting it simply; these poems talk about the relationship between softness and toughness, between vulnerability and violence, and most importantly, between sex and sacredness, until the conflicts become symbioses. After all, “the right kind of softness can unravel kings†and “wine coolers in Texas summers can taste like praying if you hold your mouth right.â€Â ‘Redefining The Classics’ is a must read for any literature student who takes issue with “the same tired books they’ve used in the syllabus for years/creating next generation narcissists/men longing for the kind of thick/underbelly sludge of the earth/ that the beat poets waxed prettily about—keep me apart from the boys who love Bukowski /I love myself too much.â€

‘Wrong Side of a Fistfight’ is about agency through reinterpretation — of past relationships, of femininity, of aggression, of sanctity, of Zeus as a guy who “launders money through the accounts of his ‘commonwealth’ corporationâ€, and of depression as “not so much sorrow and anguish, as it is existing when you’re not sure you want to.†As is only appropriate in our times, Ashe is a meta-poet, a poet’s poet who laughs at her own craft, which is neither sacred nor miraculous to her: “Poetry makes for pretty Band-aids…show them off like children on the playground: this is where I broke my heart/and this is where it almost broke me back, but listen – don’t these similes look good on me?â€

‘Black Earth: the Holocaust as History and Warning’, by Timothy Snyder

Daniel Voskoboynik, Missing Slate Poet of the Month (May 2015)

“We recall the victims [of the Holocaust], but are apt to confuse commemoration with understandingâ€, cautions historian Timothy Snyder, in the introduction to ‘Black Earth’.

The book is ostensibly an attempt to ground our understanding of the Holocaust by examining and reappraising its origins. But in doing so, it is also an absorbing meditation on history, power, amnesia, memory and the future.

Illustrated by individual stories of loss and survival, and buttressed by formidable archival work, Black Earth begins by sweeping aside conventional wisdom around the Shoah. As Snyder observes, “[w]e rightly associate the Holocaust with Nazi ideology, but forget that many of the killers were not Nazis or even Germans. We think first of German Jews, although almost all of the Jews killed in the Holocaust lived beyond Germany. We think of concentration camps, though few of the murdered Jews ever saw one.â€

Snyder’s chronological analysis then takes the reader from idea to execution, focusing on a few central themes: firstly, that Hitler’s worldview was profoundly ecological. In his eyes, nature was an arduous struggle between races for food, resources, land and comfort. Plundering the East, and removing the “pestilence†of the Jews, would become the “logical†outcomes of this depraved ideology of conquest.

Secondly, that the breakdown of states and institutions in Nazi-occupied Europe was the decisive precondition for genocide. Stripped of the safeties of citizenship, Jews were most vulnerable in states that had been obliterated. The degree of state destruction determined why around 99% of Estonian Jews were murdered, and 99% of Danish Jews survived.

Finally, the haunting closing reflection in ‘Black Earth’ is that scarcity and ecological panic can open up the political space for forces of horror. The paranoias that stem from deprivation and natural disasters, are easily directed towards scapegoating or ethnic blame. As the violent impacts of climate change increasingly unravel, we must not forget that furies of the atmosphere, can unleash the furies of humanity.

Snyder’s assertive approach has received criticism for its historiographical faults and overly forced angles. But the shortcomings of the book do not detract from its pressing message: we cannot be complacent about history. As Snyder writes: “The history of the Holocaust is not over. Its precedent is eternal, and its lessons have not yet been learned.â€

The past is a mute warning, and ‘Black Earth’ is a timely plea to listen.