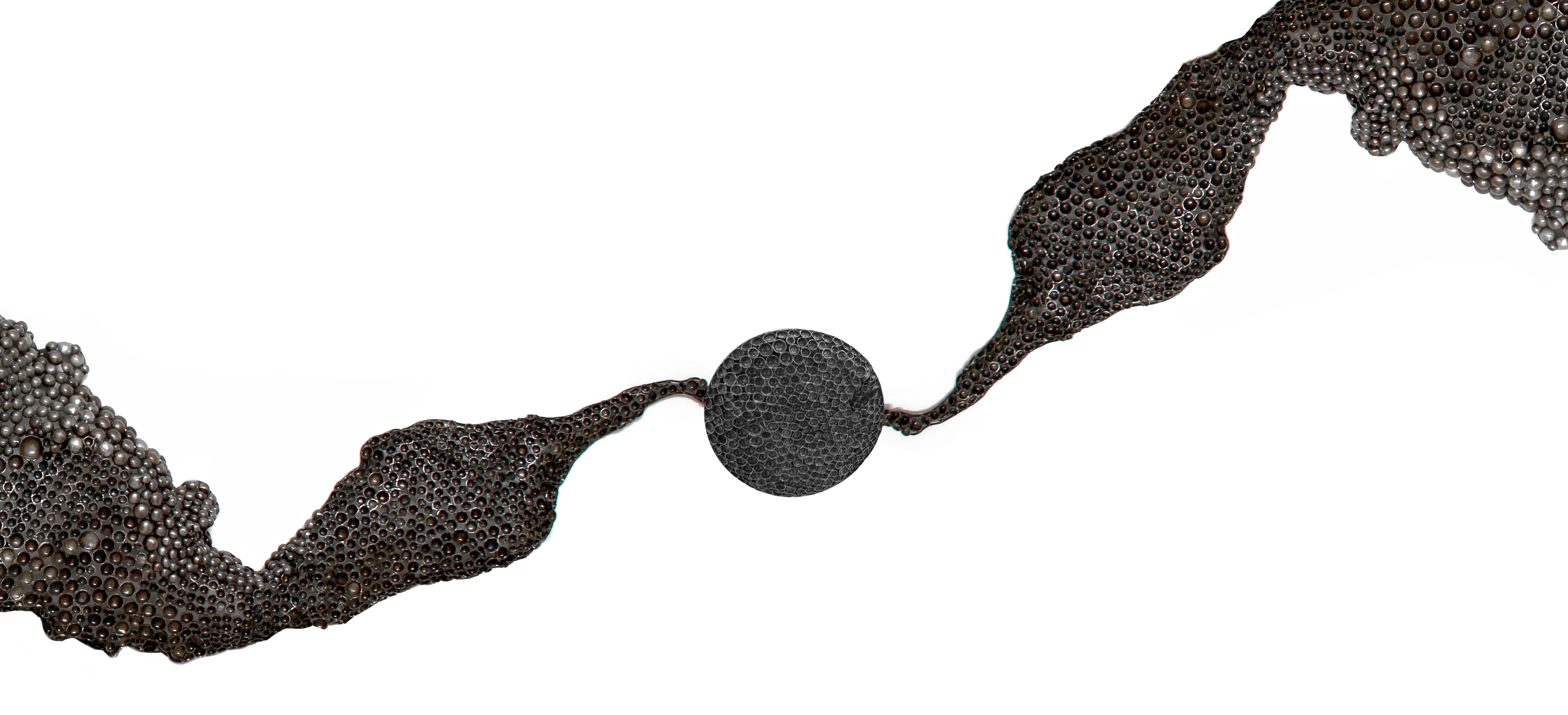

Creation of Earth by Abdullah Qamar. Image Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery.

I was Dorje Phagmo. I don’t remember being anything else; my teacher and the lamas recognized me when I was nine months old. Childhood was pure joy; my teacher was always near. She was strict but I was greatly loved. My birth mother visited often, and the anis were fifty-nine more mothers to me. Samding nunnery was some distance from Nagarsi on the trade road between Lhasa and India. We had a fine statue of Buddha, but we were not a rich nunnery. Many women made pilgrimages to Samding and sometimes travelling lamas stopped but we did not encourage visitors. My immediate predecessor despised the traders who detoured to Samding to worship. She retreated to the meditation cave high on the mountain. When the philangs invaded with their guns and shiny buttoned coats, and asked to make her acquaintance she was sure to be “in retreat.†The abbot of Palchor Chode sent word that the English did not come to steal, they wanted to learn about our history and practices. But she did not believe him. Later the Abbot came, himself, and said they did not believe a woman who was never in her rooms could be as important as he told them she was. She laughed and said she did not believe they were as important as the abbot thought they were. They had come but they would not stay as other invaders did not. She said that and I believed no one would ever dominate out mountain high country. What did we know? The anis were peaceful women, worshiping peacefully.

Our lives were quiet and worshipful. We lived high on the mountainside but trees flourished because they were tended. How I loved the apricots! I called them little suns, and they tasted like the sun. I suppose sometimes I was petulant and impatient as a child is likely to be but the love that surrounded me was higher and stronger than the mountains that filled our world. The glacier cold was never a part of my world.

My own, that is my distant ancestress’s, story of how she attained the name Dorje Phagmo, was told to me from before I could remember it. The name means

In the early 1700s the Jungar Tartars–Mohammedan warriors–were bent on conquering and converting all of Asia. They invaded Tibet and laid waste to monasteries, killed lamas and anis and stripped the gold from our gilded Buddhas. Those at our nunnery thought we would be overlooked because we were hidden from the regular tracks. But that was not to be. One day the farmers and villagers came and begged us to hide, as they were going to hide. They knew the invaders would burn their homes and our nunnery and the nearby monastery. The story of Tartar ruthlessness had spread through the land. But I–for I am my ancestress as my teacher always told me–refused to abandon our home. It was the only home most of us had ever known. My teacher had become a very old woman; she had taught me the power secrets that she, herself, had eschewed, powers a teacher will not need but that an abbess may need to protect the anis in her care. I do not know just what I did, for in this life, as I will tell, I was only a child and had not been taught all the scriptures and none of the deeper secrets.

The Jungar Tartars arrived at the gates on their horses with silver on their bridles and long steel swords in their hands, long black beards and booming voices. They demanded we open but they got no answer. They broke down the gate and found the courtyard full of pigs gathered around the largest, angriest, snortingest sow they had every seen. Swine and dogs are so abhorrent to these Mohammedans that they turned their horses and rode away even faster than they had come. I loved that story and always felt myself, the Thunderbolt Sow, Dorje Phagmo, huge and powerful and wonderful in my protecting anger. As a child I practiced snorting, delighted when the anis and monks pretended terror and then doubled up in laughter and my snorting turned to giggles.

I was still almost a child, fourteen years old, when the Red Guards came to Tibet in 1961. My teacher had taught me the scriptures and prayers but I was still learning the basics; I had not matriculated, fully earning my title, those lessons would have taken ten more years. Teacher had heard from the peasants about the Chinese in Lhasa and that the Dalai Lama had fled to India. All of Tibet, even all of China, was overrun with angry young men who, like the Jungar Tartars, burned and destroyed. The monks warned that if they came to our almost hidden monastery they would rape and murder and destroy. The farmers, always our friends, told me to hide in the meditation cave high up near the mountaintop. They promised to provide what food and milk they could. The cave was hidden among bushes and boulders. Once I had remained there three months, three weeks and three days meditating. I had no fear of being alone. But I was grateful that my teacher came with me because she wanted to teach me whatever power secrets she could, for she was growing elderly and frail and her aim was to equipment me with what skills could save me if I were not killed.