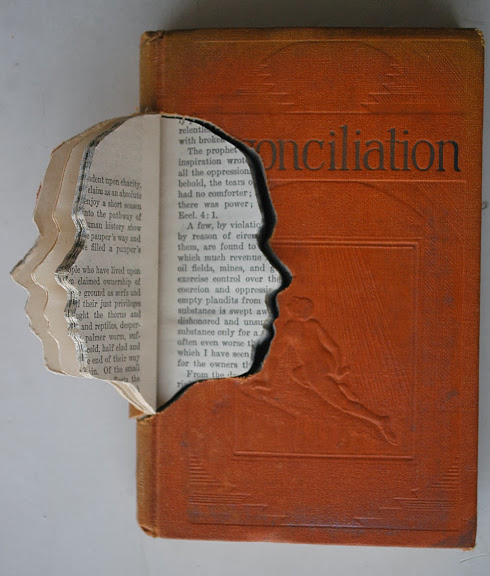

Reconciliation by Fraz Mateen. Image Courtesy ArtChowk Gallery

An examination of what Bangladeshi writing used to be and where it stands now

By Dr Rashid Askari

The Emergence of a New VoiceÂ

English is no longer the linguistic or literary patrimony of the Anglo Saxons or their direct descendants. It is now a universal language and the ideal vehicle for global literatures. By the British colonial train, English has traveled the entire world, come in touch with myriad people and their languages and established itself as the world’s lingua franca. Not only as a means of communication between the peoples of opposite poles and hemispheres, but as a medium of creative writing, English has consciously been taken up by writers of formerly colonized countries. These  writers exploit the King’s/Queen’s language in their own sweet ways to suit their own literary bents. And the number of exploiters is multiplying with the rise of postcolonial/diaspora consciousness, or people who want to get over the hangovers left behind by their colonial past.

In South Asia, most of the prominent English-language writers are Indian, Pakistani or Sri Lankan. The situation in Bangladesh is slightly different: “owing to a linguistic loyalty tied to Bangladeshi nationalism, begun with the Language Movement in the 1950s and its refusal to abandon Bangla for the externally enforced and mandatory use of Urdu by politically dominant West Pakistan, English-language literature in Bangladesh has taken longer to assume its role in the subcontinental boom pioneered by writers from India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka†[2]. Nevertheless, this stream of creative writing in English from South Asia has reached the present literary arena of Bangladesh, and can be called “Bangladeshi Writing in English” (BWE). This new generation of writers, “[a]fter centuries of domination by Bangla and Urdu languages in the writing arena of Bangladesh… now appears to be equally fascinated towards English language. The rising writers of Bangladesh today have made their marks on the international stage of writingâ€Â [3].

The Nature of Bangladeshi Writing in English: Creativity and Originality

By “Bangladeshi Writing in English”, I mean to include the whole corpus of creative work of writers in Bangladesh, and the Bangladeshi Diaspora, who write in English, but whose mother tongue is Bengali or some other indigenous language(s). This particular genre of writing could also be given other name(s). But, in my opinion, BWE better describes the nature of the work being produced. However, one thing must be remembered: not all writers who write in English in Bangladesh should be included in BWE. A large number of writers are writing in English for newspapers, magazines and journals, and these professionals should not be indiscriminately welcomed to the BWE genre. This field of writing includes only creative writing in English, i.e. poetry, drama, fiction and non-fiction, or writing that has considerable literary and artistic merit.

The Literary Background of Bangladeshi Writing in English

The literary background of BWE can be traced back to pre-Independence and the undivided Bengal. Towards the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, around the time when English learning was gaining ground in Calcutta — the capital of British India, an enthusiasm for writing in English arose in Bengal. Since Macaulay’s ‘Minute’ in 1835, English has been the preferred means of expression of the ruling and intellectual elite, as well as the language of instruction in higher education. With the spread of English was born a special kind of literature called ‘Indo-Anglian literature’, aka ‘Indian English literature’, which was Indian in content and English in form. The literary heritage of Bangladeshi writing in English can follow its roots back to the same source. Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1774 -1833), the father of the Bengali Renaissance, was also the “father of Indian literature in Englishâ€Â [4]. He was the pioneer of a literary trend that has extended over a vast area of the subcontinent, including Bangladesh. Like Indian English literature, Bangladeshi English literature is Bangladeshi in content and English in form.

The first book of poems in English in undivided Bengal was ‘The Shair and Other Poems’ (1830) by Kashiprashad Ghose. Michael Madhusudan Dutt (1824—1873) took to writing poetry in English under the influence of English poets like Thomas Moore, John Keats, Lord George Byron, among others. Although he suffered setbacks in his early career, his genius for English writing prevailed, especially in his two English poetry books ‘The Captive Lady and Visions of the Past’, both published in 1849. His poetry was well-received by highly educated Bengalis and other English speaking circles. Toru Dutt (1855—1876) in her very short life, attracted global attention by writing and translating poetry into English. Her ‘A Sheaf Glean’d and French Fields’ and ‘Ancient Ballads and Legends of Hindustan’ were published in 1876 and 1882 respectively. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee (1838—1894) won recognition for his novel ‘Rajmohan’s Wife’. Rabindranath Tagore (1861—1941) exhibited great talent with English writing.  He began by translating his own work into English, which led to a considerable amount of original writing in the language, as well as his translations of others’ work into English. Nirad C. Chaudhuri (1897-1999) was the quintessential English writer of Bengal stories whose success reached new heights in the genre.