More a syndrome than a disease, this essay serves as a public service announcement.

By Thirteen

January 2011 – I remember most of my classmates walking hurriedly to the lecture hall. A leading neurologist from the USA was to present a talk on epilepsy that day. The lecture began with tales of the Dark Ages, when people used to burn epileptic patients alive. Many of these being women, they were accused of witchcraft and wizardry. Later on, in the Middle Ages, they were referred to saints for treatment because they were deemed incurable. After an awe-inspiring fifty minutes, the lecture ended with a note on how we seem to have devolved when it comes to our perception of epilepsy. In this day and age, we treat epileptics no better than people in the Dark and Middle Ages did. The thought has not left my mind ever since.

January 2011 – I remember most of my classmates walking hurriedly to the lecture hall. A leading neurologist from the USA was to present a talk on epilepsy that day. The lecture began with tales of the Dark Ages, when people used to burn epileptic patients alive. Many of these being women, they were accused of witchcraft and wizardry. Later on, in the Middle Ages, they were referred to saints for treatment because they were deemed incurable. After an awe-inspiring fifty minutes, the lecture ended with a note on how we seem to have devolved when it comes to our perception of epilepsy. In this day and age, we treat epileptics no better than people in the Dark and Middle Ages did. The thought has not left my mind ever since.

Epilepsy, a frightening but mostly misunderstood entity, is better classified as a syndrome than a disease. A condition as old as human civilization, its mere mention has a tendency to send shivers down one’s spine, doctor or patient. Despite ongoing research, an understanding of its cause remains elusive at best and the treatment only sub-optimal.

Misconceptions about epilepsy feed on human beings and their fear of the unknown. The disease is often attributed to supernatural beings such as djinns and evil spirits, and sometimes patients themselves claim the ability to converse with God.

What the general public remains oblivious to is how the symptoms of epilepsy largely depend on the area of the brain involved. If, for instance, the temporal lobe is affected, the patient is likely to vocalize during an attack, often speaking in a different tone or voice, saying things he/she is not aware of and coming across as frighteningly disoriented. If the frontal lobe is implicated, the patient may appear to have major personality issues. Some people, especially children, have “absence seizures†in which they just gaze into space for some time, then switch back to reality just as swiftly.

Epilepsy does not keep anyone from leading a normal life. Scientifically speaking, the syndrome has no known impact on a person’s IQ. Some activities – such as driving, swimming and cycling – must be supervised in epileptics, lest they endanger their lives. Epilepsy presents special problems in pregnancy. Many mothers-to-be stop taking preventive drugs, thinking that they will harm their baby. While this is true of most drugs can, an epileptic fit during pregnancy would have a much more adverse affect, including possible miscarriage. Expectant mothers are always advised to continue taking their medication during pregnancy.

Diagnosing epilepsy in a child or adult is as difficult for the physician as it is for the patient. Because of the stigma attached to the label of an epileptic, parents rarely ever come to terms with the diagnosis of their child, and in desperation seek help from saints instead of complying with the advised therapy. Certain forms of epilepsy that manifest during a patient’s childhood stop having an impact during his/her adulthood. Many epileptics, with long-term therapy, remain fit free for years and even after the drugs have been tapered off. The process is nevertheless gradual and patience is mandatory.

As doctors, we do our best to educate those around us about the syndrome and how best to deal with it. Yet, a helper in our college canteen, Khala Kalsoom, took her daughter to the mountains of Nathiagali to be “cured†by a saint. Although I don’t know how successful her effort was, I still consider it a personal failure that she lacked the awareness to accept and act upon the diagnosis given by her daughter’s neurologist.

What we need is a comprehensive program that can target affected individuals, their families and the general public and educate them about epilepsy. That would at least abate some of the anxiety of this notorious entity, and give them the courage to fight the stigma in order to lead a normal and superstition-free life.

Disclaimer: Names have been changed to protect privacy

Â

Thirteen is a grouch dispassionate about the shenanigans of the universe and all that it has spawned, yet continuing the rather Sisyphean pursuit of pointing out what ails it.

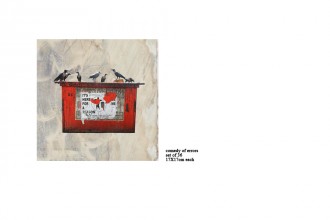

Artwork by Ahsan Masood.