Following a few close calls, narrower victories that he’d become accustomed to, Condor started flying with some of those wrecks that he’d salvaged and had his mother stitch up, and which his father still welcomed so proudly when he brought them home, often by the armful. Still ruffled his hair and said: Look at him, my son, he may become even better than me yet! Gave him more used and blood-stained razor blades to fasten to the edges of these trophies.

Almost immediately as he adopted this strategy, started making use of these substitutes, he began to lose. They were not as good fabric as his blue beauty, many of them not being silk, or anything that might pass for silk, even from a distance. They were cotton or lycra or plastic, in some cases, and he didn’t take the time to practise with them, didn’t learn how to adapt his tugs and twists and his steps forwards and backwards and his pivots and jumps to their differing textures, their differing weights.

Now, when his wrecks went down, the Bird-God didn’t leave his eyes on the winner, but set them on Condor, staring for what felt like minutes before turning away, back to the beach.

Once, after a loss, Condor went over to him, asked for a cigarette. The Bird-God obliged, and lit it for him, and they both sat there with their legs dangling in the dead space over the edge of the roof.

I think it is four miles, he said.

He gestured upwards to a couple of hang gliders soaring overhead, vulture-swooping down towards the wedge of clear beach.

I have been watching them, he said, and I think I have worked out their speed and the distance from the time it takes for them to land.

He raised his wrist, and a watch glowed, far too big, around it, rattling and clinking, silver and gold. It used to be my father’s, he said.

I think we should fight, he said.

But you must use your best bird.

***

The date was set for the end of the week. Every night of the week, Condor had trouble sleeping. Had so much trouble, in fact, that he could never be certain afterwards, after all of this was over, that he actually had. The week was a dream. The next month was a dream.

No sooner had he come home, having lost another few kites, to the barely concealed disappointment of his father, and eaten, not even finishing his meals, pushing the rice and the black beans away with only a few forkfuls taken; no sooner had he climbed into bed than he was out again, springing silently out of his window, down the drainpipe, his turquoise beauty under his arm.

He had to renew, to refresh his confidence and his touch. He watched the kite glow against the full moon, saw it turn into a diamond of ocean, and looked down for any barbecue fires on the beach, but there were none. He tried to keep focused, to keep his knees bent but not too bent, to keep his grip loose but not too loose, to thrust and sweep and slice at the moon as though he might actually break it; as though he might crack the top off the egg and find its yolk like a galaxy burning inside.

Some nights that week, as he was leaving before sunrise, to hide from his opponent that he’d been practising, that he’d been worried, he had caught a whiff of smoke. His bare foot had crumpled something that might have been a match-head. But he never saw a face, a silhouette, never noticed the pulsating red of a cigarette tip.

When he got back home those nights, he was sure he didn’t sleep.

***

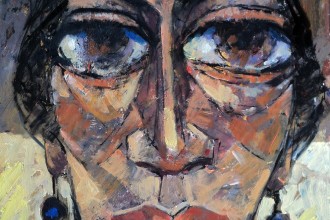

The Bird-God was back as the locus of the group. By the time Condor arrived for the contest, there he was, standing proudly, loudly, telling them all the story of how his own favourite kite had been made.

Though they must each have heard this story at least a few times, he still felt the need for a visual aid, and they didn’t begrudge him. Rather, they cheered as he held his kite aloft to illustrate the tale.

It was plain white cotton, expect for a couple of spots and a streak of rust-red, and, when he held it up, the sun came through and those spots and that streak seemed to burn with a low-lying flame.

The white, the cotton was all that remained of the sheet that had been on his mother’s bed in the whorehouse, the day she’d given birth. The spots and the streak were her blood, the dearest and truest memento of her that he had. Along with the lock of her hair that his father had saved and passed on to him, and which he had used to hem the sides into their pristine diamond shape.

And the edges, their sharpness was the sharpness of his father’s throwing knives, and of the two halves of his mother’s money clip, which had broken in two, she had made so much money, she had been such a famous and sought-after whore.

Another cheer at this point.

As the Bird-God lowered the kite, he set his eyes on Condor, and on his turquoise beauty, and grinned, and motioned to him to get started.

***

Never had he felt so nimble, so well-poised, so awake and so focused. The pull and release of the string over the subtle scar between his first and second fingers was just right, was always spot-on, so delicate, so quick. His kite ducked and swooped, slicing in towards the Bird-God’s line.

But the Bird-God was deft as well. Withdrew his kite from danger, danced backwards with bent knees, manoeuvred into a killing-strike dive of its own.

As they all milled around in the moments before take-off, the others all repeated the line he’d heard hundreds of times before, that: The Bird-God has never lost. That: We are so sorry for you. We are sorry already.

Condor stepped forwards, however, jumped out of range. Came to land awkwardly on the rim of the roof, but just about held his balance. Pivoted. Made another dive.

Missed by barely an inch.

The Bird-God shot him a glare. Looked up again, but not quite at the kites. He must be distracted, thought Condor. This was his chance.

He jumped back, back, then wrenched at the string, burning again at the scar between his fingers. His turquoise beauty arrowed down, cutting a direct diagonal for the Bird-God’s line.

Then all was shadow. He lost track of his kite, with the sun no longer coming through it, no longer transforming it into a bright scrap of sea. A hang glider was passing, low and close, and he felt his line veer and shake with the down-force. Then he felt it go slack.

When the sky cleared, there it was, tumbling, and the Bird-God was already off running, knowing before it did where it would land.

***

And then what? And then what? his grandkids might one day ask him. But he wouldn’t be able to tell them, not for certain, because he didn’t quite know.

None of them did. Not Paradise, not Sparrowhawk, not Eagle, not Phoenix, not Cockatoo.

He didn’t see entirely what happened next, because he couldn’t bear to look, first putting his hand over his eyes, then turning away.

There was a mirror of the pattern of cheering as he must have been coming back the other way, and then a gasp, a kind of collective wail, and then another cheer, as, presumably, he made it home safe.

But no.

It was only his own kite, drifting skywards, his most precious possession, his most treasured keepsake, drifting away on the breeze. Condor turned around just in time to see this, alerted by Cockatoo’s terrified cries. The sun came through from behind it, tinder-striking the dots and the streak into low-lying flame.

He rushed towards the rim of the roof, driven by instinct to the same spot at which they’d so often leaned or sat or stood to watch the white sand and the ocean. They were all lined up, peering over, squinting into the abyss.

There was no sign of his body. They could see vague shapes walking, hear the echo of the footsteps, but no screams, nothing that might indicate a body had been found.

A fearful murmur began at the back of the group that maybe he had really been sacred. Perhaps he had ceased to walk the tightrope, had simply vanished from this world, returned in triumph to the place of the gods.

At first, some of the older, taller kids wanted to laugh this off, say: No, he is dead, we will hear the screams soon. But the screams didn’t come, and talk soon started about his parents, the cat and the pitbull, and that talk became a conviction that they too had been gods.

***