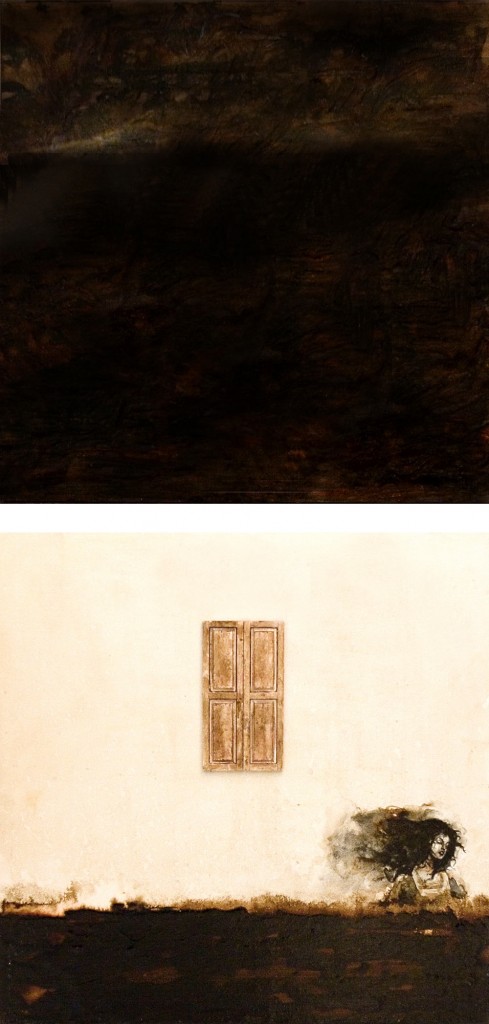

Behind Closed Doors 11 by Saqib Hanif. Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery

By Adda Djørup

Translated from Danish by Peter Woltemade

The girl drawing is Sara. She is sitting at the table in the little living room. She has a light brown sweater on. She is bending her head over the paper. She is dangling her legs. One is stretched out under the table, the other bent back under the chair. She is wearing brown lace-up shoes, long white stockings, and a skirt. I have often wondered about those shoes and those stockings, which look oddly old-fashioned. There are white-yellow spots of sunlight on the table and on her hands, hair, and forehead. Through the window and onto the floor in front of her fall fat yellow squares of afternoon sun. An indeterminable potted plant has lost a few leaves on the windowsill and casts a blurred shadow on one of the squares on the floor. On the far end of the table, the end nearest the window, stands the dark green porcelain vase with a bouquet of red tulips in it. In the background, behind Sara’s back, a door to the office, which is in shadow, is open. Caught as it is by the light and the subject in the foreground, one’s gaze quickly slides past the door opening. Only when one looks closely at the picture does it occur to one that one might join the childish form sitting in there, in the office, well pressed down into the armchair, watching the scene being painted in the other room from there, from behind. One observes the observer, and inevitably one then again begins to observe the central motif: Sara, drawing. Protectively or in defiance, she has laid her arm in front of the paper so that one cannot see what she is drawing, and everyone has forgotten what it was. It could be anything, and for my part I must admit there is something horribly scary about forgetting: In the beginning, we salvage what we can: wreckage, fragments of a whole that in the beginning remind us of the whole of which they were a part but slowly, unnoticeably, replace it. We drag it along with us, from house to house, from wall to wall, year after year, until one day we look up from the newspaper or glance at it sideways as we pass and see an empty shell from which emptiness spreads: an incomprehensibly great and desolate certainty that we have forgotten. That is a terrible moment. Then we hang the fragment, which now reminds us more of our forgetting than of that which was there, in the guest room. We cannot throw it out, after all—this is forbidden us by our fear of the unthinkable, of that which is worse than death: total forgetting, a total lack of being.

The picture paints itself again and again. It sets a scene: a room, a floor, a window. A table, a chair. Squares of sunshine on the floor. An indeterminable potted plant on the windowsill. It places the green porcelain vase on the table and arranges a bouquet of tulips in it. It pulls the chair out and sets a girl in a light brown sweater on it, puts a pen in her hand and says: “Just draw what you would like to.” It bends her head over the paper and lays her arm in front of it protectively or in defiance. It stretches her one old-fashioned-stockinged leg forward, bends the other back, and lets her hang on the edge of the chair like that with her legs purposelessly promenading in the air. The picture paints itself: opens the door to a room in shadow and presses a childish form deep into the armchair. A child who, relieved that the choice has not fallen on him (it is indescribably boring to have to sit still for so long) and occupied as he is with (secretly, hidden by shadow, he believes) observing the scene, has not discovered that it captured him. The picture is hanging in the guest room of the summer house. The room that was once mine and Sara’s. It paints itself when the house is empty and locked up, in honor of the shifting light. It paints itself while the family sits in the kitchen when no guests are there, or while the guest that is there is lying in bed and dreaming of other houses, other beds. When the guest wakes up and takes a look at it to see how it might look in daylight, it leads his gaze around like a guide at a museum: “Note the hand there, the tilt of the head, the angle of the light; look at the door there.” Perhaps the guest is not the type that is interested in art; perhaps he just gets the feeling of something that for a moment is wandering around at the edge of his life, while he looks for something in his toiletries bag, stretches, gets ready for breakfast. Perhaps the feeling leaves him immediately, and perhaps it is left hanging for a moment as one of thousands of sensory impressions that are mixed with a thousand ephemeral thoughts.