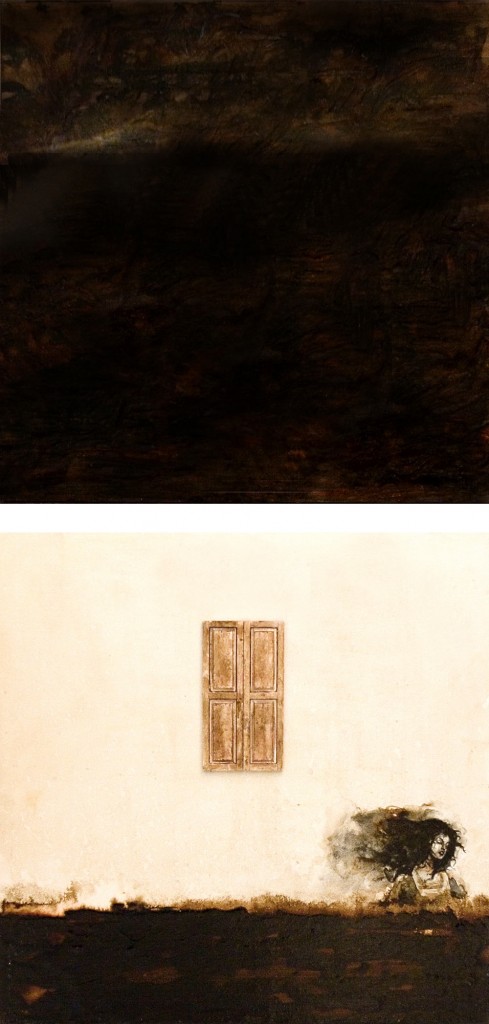

Behind Closed Doors 11 by Saqib Hanif. Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery

By Adda Djørup

Translated from Danish by Peter Woltemade

The girl drawing is Sara. She is sitting at the table in the little living room. She has a light brown sweater on. She is bending her head over the paper. She is dangling her legs. One is stretched out under the table, the other bent back under the chair. She is wearing brown lace-up shoes, long white stockings, and a skirt. I have often wondered about those shoes and those stockings, which look oddly old-fashioned. There are white-yellow spots of sunlight on the table and on her hands, hair, and forehead. Through the window and onto the floor in front of her fall fat yellow squares of afternoon sun. An indeterminable potted plant has lost a few leaves on the windowsill and casts a blurred shadow on one of the squares on the floor. On the far end of the table, the end nearest the window, stands the dark green porcelain vase with a bouquet of red tulips in it. In the background, behind Sara’s back, a door to the office, which is in shadow, is open. Caught as it is by the light and the subject in the foreground, one’s gaze quickly slides past the door opening. Only when one looks closely at the picture does it occur to one that one might join the childish form sitting in there, in the office, well pressed down into the armchair, watching the scene being painted in the other room from there, from behind. One observes the observer, and inevitably one then again begins to observe the central motif: Sara, drawing. Protectively or in defiance, she has laid her arm in front of the paper so that one cannot see what she is drawing, and everyone has forgotten what it was. It could be anything, and for my part I must admit there is something horribly scary about forgetting: In the beginning, we salvage what we can: wreckage, fragments of a whole that in the beginning remind us of the whole of which they were a part but slowly, unnoticeably, replace it. We drag it along with us, from house to house, from wall to wall, year after year, until one day we look up from the newspaper or glance at it sideways as we pass and see an empty shell from which emptiness spreads: an incomprehensibly great and desolate certainty that we have forgotten. That is a terrible moment. Then we hang the fragment, which now reminds us more of our forgetting than of that which was there, in the guest room. We cannot throw it out, after all—this is forbidden us by our fear of the unthinkable, of that which is worse than death: total forgetting, a total lack of being.

The picture paints itself again and again. It sets a scene: a room, a floor, a window. A table, a chair. Squares of sunshine on the floor. An indeterminable potted plant on the windowsill. It places the green porcelain vase on the table and arranges a bouquet of tulips in it. It pulls the chair out and sets a girl in a light brown sweater on it, puts a pen in her hand and says: “Just draw what you would like to.” It bends her head over the paper and lays her arm in front of it protectively or in defiance. It stretches her one old-fashioned-stockinged leg forward, bends the other back, and lets her hang on the edge of the chair like that with her legs purposelessly promenading in the air. The picture paints itself: opens the door to a room in shadow and presses a childish form deep into the armchair. A child who, relieved that the choice has not fallen on him (it is indescribably boring to have to sit still for so long) and occupied as he is with (secretly, hidden by shadow, he believes) observing the scene, has not discovered that it captured him. The picture is hanging in the guest room of the summer house. The room that was once mine and Sara’s. It paints itself when the house is empty and locked up, in honor of the shifting light. It paints itself while the family sits in the kitchen when no guests are there, or while the guest that is there is lying in bed and dreaming of other houses, other beds. When the guest wakes up and takes a look at it to see how it might look in daylight, it leads his gaze around like a guide at a museum: “Note the hand there, the tilt of the head, the angle of the light; look at the door there.” Perhaps the guest is not the type that is interested in art; perhaps he just gets the feeling of something that for a moment is wandering around at the edge of his life, while he looks for something in his toiletries bag, stretches, gets ready for breakfast. Perhaps the feeling leaves him immediately, and perhaps it is left hanging for a moment as one of thousands of sensory impressions that are mixed with a thousand ephemeral thoughts.

The day is gray and white; it lies like a clammy weight on the eyelids. A dirty milky light hovers over the naked yard. The hundred-year-old bamboo has bloomed: it is withered and ugly. The wheelbarrow is rusty and ugly. The apple trees are gnarled, black, and ugly. The birds are disheveled and ugly. Everything looks as if the dirty day has sucked all the life out of it; to think that a day can be so ugly. And the snow does not want to come and make it pretty again—the snow does not want to. Ugly, ugly, ugly …. He repeats the word until it loses its meaning; everything bores him; there is a hole in the middle of the day; through it everything flows out and finally the darkness comes, much too early, and puts the lid on. He hates Sundays, hates Sundays without Sara, hates all days without Sara. He cannot stand thinking about it, but he thinks about it nevertheless, as an experiment. And he cannot stand it. For Sara was the necessary break in the day’s kaleidoscopic pattern, Sara was the space between himself and the others: Mother and Father. All that could prevent them from collapsing, becoming entangled with each other, condensing into a dark lump, and sinking. Evidently. Because now that is the way it is; together they weigh so much that the house has begun to sink like a stone, down toward the bottom of the darkness. And the snow does not want to come; the snow does not want to. He sits in the glass capsule of the terrace room and stares out at the garden, he, who was once I, a human being with one purpose only: to keep himself floating. But there are incomprehensible things adding weight to his weight, and what made everything float before is now gone. It is infinitely complicated and demands a new and hitherto unknown strategy. He has a lifetime to find it, but his thoughts turn to nothing but crying. The more tears that fall, the emptier his body becomes: a heavy emptiness just like that of the sky, heavy from nothingness. Then comes the pitch blackness, and at the bottom of the pitch blackness he accepts a kind of truce: Sara is here, one just cannot see her right at this moment; she is out in the garage; in a moment she will come in through the front door; she is sitting at the kitchen table. But if one tries to find her, she will disappear. If one listens for the sound of the front door opening, she will be unable to get in. If one goes into the kitchen, she will have just left. One must be quiet, as quiet as she is, as invisible as she is. One must make room for her. One must be careful, and then she will be here again, in a way. Then the room will expand again, then the distance between them, between him and Mother and Father, will increase again, then they will again begin to float.

The last remnant of remembrance—what is it? What does it turn into? A swarm of indistinct images at the edges of one’s vision, perhaps? Or a single image that holds one, a last moment? In my case, then, it could be the image of my wife, my children, or precisely that picture, Sara drawing, at which I stared while I executed a series of solemn and deadly serious childish incantations. In the end I tried to hurry Sara’s mystic rebirth by promising never to step on the lines, never to forget, to always answer the telephone after three rings. My mother gave birth to my brother, who was nine years younger than I, and the matter was resolved.

Of course I do not imagine that the picture paints itself, or that the world was ever whole, with or without Sara. I do not imagine that I have remembered what is important and forgotten what is unimportant. I do not imagine that childhood sorrow over the death of a beloved sister remains intact for more than thirty years. On the other hand: I do not imagine that I am not imagining anything. For on the other side of the thirty years there is a very early morning on which all the grayness and ugliness of a dirty day and night disintegrates in a mighty snowstorm, as recently as this morning: I wake up and look out into the room, searching for that which has awakened me. It is everything that has awakened me: my wife talking in her sleep; the smell of summer house, of a house that is seldom inhabited, of sweaters in sea chests, damp books, old mattresses, and cold ovens. The smell of our own absence barely hidden by the thin veneer of the smell of a short winter vacation, of cooking, dry firewood, the kids’ messy attempts to make popcorn on the wood-burning stove, cleaning, comforters brought from home, and new books. And there is more: there is the certainty of the place of everything in relation to everything else, from the dead daddy-long-legs on the windowsills and the knots in the wood floors to the mousetraps in the attic and the crockery on its hooks. And more: there is the position of the house within the summer house area, in relation to the harbor path on the one side and to the sea and the beach path on the other side. It crisscrosses: It is the kitchen clock in relation to the stairs down to the yard, the pile of firewood in relation to the bed I am sitting on; it is the view from every single window; it is the sight of it, and the smell and the taste and the feeling. It is this entire summer house world in which time once stopped and set things up as they should be, so as to be able to pass by on rare occasions and adjust a minor detail: set the clocks to summer time or winter time, switch a couple of pictures, pull the armchair closer to the window, replace a white telephone with a red one of the same kind, put a new old vacuum cleaner in the cleaning closet, hammer in ten big nails in the hall and then never get a proper hook put up. And, at intervals of years, present a new, wonderful child. It is the empty guest room. That is what has awakened me. The truce is ended; we have an account to settle.

I get up, and then I look out the window … see the snow. The whole world lies at once hidden and illuminated by the snow falling from the sky, which one cannot see because of all the—snow. I quickly get a sweater on over my pajamas and boots on my feet and on the way out take a peek in where the children, who look like the angels they are not, are sleeping. I hesitate only briefly outside the guest room and then open the door. It is empty. But it is full. It is full of a fullness that tumbles out toward me. I step aside, step away a step, leave the door open, the door to the yard, too, and leave, staggering …. I walk out to the middle of the lawn, a year lighter with every step. I stand there, still with the warmth from the bed under my clothes and look up in the snow that is indiscriminately tumbling onto me and everything else. The trees, the roof, the lawn, the hedge are already completely powdered over and the beach path is already invisible.

“It is the sky that is falling,” says Sara, “and we who are standing.”

Adda Djørup was born in 1972 in Denmark, where she grew up. She has lived in Madrid and Florence for several years respectively and has written poetry, prose, and drama. Among other distinctions, she has received the EU’s Literature Prize and the Danish Arts Foundation’s three-year working grant.

Peter Woltemade is an American-born literary and commercial translator based in Copenhagen. He holds a Ph.D. in medieval German literature from the University of California at Berkeley (2005). His translation of an excerpt from Karl-Heinz Ott’s 2005 novel ‘Endlich Stille has appeared’ in The Brooklyn Rail. He is currently translating the short fiction of Maja Elverkilde in consultation with the author.

©Adda Djørup & Rosinante, 2007. Published by agreement with Gyldendal Group Agency.