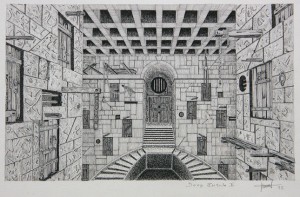

Artwork by Henri Souffay. Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery

By Bryan Patrick Young

This will kill that. The book will kill the edifice.

~Â Victor Hugo(1)

Architecture, like a character in Greek tragedy, has been haunted by Hugo’s prophecy: the printed text and its successor the digital, facilitating the word’s promulgation, assures the defeat of its rival. As demonstration, this essay will, like sacred drama, enact the ritualised death of architecture using fictional text as illustration.

The architectural historian Sir John Summerson laid down two conditions for the illustrator of architectural fantasy:

He must not lose sight of scale. Once that is lost or even rendered ambiguous, his drawing becomes incapable of communication in architectural terms. Nor may he employ forms which have not some reference (however slight) to our experience of executed architecture; otherwise his work departs altogether from the architectural sphere and must look for its justification either in qualities residing in itself or to its usefulness as a representation of some organisation which may be sculpture but cannot be architecture.(2)

These two conditions will be met in our essay, though its fantasies will be fiction, eschewing the usual procedure of illustrating architectural theses with drawings. Instead of the conventional entourage of architectural depiction, human figures, vehicles, trees, and background; fictional elements will be used, such as character, plot, and setting.

The proposed setting is an imposing edifice dedicated to the appreciation of fine literature. The main halls, there being nine, will correspond to the nine natural divisions of Literature:

Tales of Idiots,

Interplanetary Travel,

Dickens,

Rhyming Poetry,

Poetry that Doesn’t Rhyme,

Histories,

Sad Tales,

Translations from the Hebrew,

and The Occult.

The building will front a broad plaza for the festivals devoted to the literary arts, and parades, and for the performances that will be made by Living Lions. The façade the building presents to this plaza should be suitably monumental. Naturally the portico must have nine columns of a noble order, one for Idiots, one for Space Travel, etc. Each column will be carved, like Trajan’s column, with Pecksniffs, Queequegs, Glorianas, etc., and decorated in stunning colour. These columns will be the most celebrated aspect of the building, and portrayed on postcards on sale in the gift shop.

Naturally the Institute’s library has one of the world’s most extensive literary collections, and it is imperative that we reach it. Among that collection may be a volume, entitled ‘The True Source of the Three Grecian Orders as Shewn in Biblical Passages’, written by Cornelius Bainbridge, first published in 1784. How on Earth would the Institute of Literature come to possess the one remaining copy known to exist of this architectural treatise? It was owned by the architect Thomas Kneal (later Sir Thomas Kneal). It was given to him by a maternal aunt in 1919, upon his induction into the RIBA. No one knows where she got it from. Kneal on one occasion suffered so much ribbing from a colleague, Clarence Hiscox, for displaying the quaint and preposterous book on his professional shelf, that the next time he was visited by members of the International Style, fearing Hiscox would draw fresh blood by ridiculing him before the other Modernists, Kneal furtively shoved the guilty volume into the hands of a surprised housemaid, urging her to get rid of it. She in turn, not sure what to do with the book, tried hiding it among Mrs (later Lady) Kneal’s detective novels. But its title looking most conspicuous, she covered it with the dust jacket from ‘The Mystery of Black River Road’, by F. Glover. She was careful to note both title and author in her diary, in case her master should have occasion to demand the book’s return. As we have no information that Kneal ever did, we surmise that ‘The True Source of the Three Grecian Orders as Shewn in Biblical Passages’ remained in his wife’s collection of novels, incognito, when that collection was donated to the Institute.

Now, although Cornelius Bainbridge may have been a crank, and his theories of the origin of architecture dusty to say the least, we know that in the support of them he had the opportunity to take measurements of a number of monuments in Mesopotamia that sadly are now because of pillage and war no longer extant. This knowledge must be brought to the light of day—It must be brought to the light of day by us. For who but we would make judicious use of it?

Angus Hatter?

Certainly not Angus Hatter! Not that firebrand, whose ‘Finding Babylon: A Structuralist Approach’ was an excuse to libellously attack rival scholars and calumniate their theories. Certainly not Angus Hatter, whose belligerent diatribes against our research methodology are unequalled in the annals of academic feuds, and who declared that there was no proof for our conclusions, and never could be a shred of evidence for such lunacies! He shall be proved wrong! Yes, and to such a feverish pitch of excitement were we raised, staring at that page in the housemaid’s diary, with the name of that author and that title painstakingly printed in her childish hand, that our fingers twitched, and we momentarily lost all sense of professional decorum, and did something that we should not have done. We tore out the page. How it seared our fingertips as we folded it and stuffed it into our pocket. And how, stealing from the room, we jumped when the elderly lady offered us iced tea! Nothing could be permitted to detain us, for the guilt was written on our face. We fled from the house like Judas from Christ.

Did Angus Hatter see that page? We never stopped to ask. Is he before us or behind us in the search? The gnawing question torments us as we glide up the Institute’s escalator. We make enquiry at the Information Desk. Behind the smiling face of the officer is a sign stating: Every Question of a Reasonable Nature Answered Courteously. So we ask her: What is the true source of the three Grecian orders? Her smile not diminishing by a single watt, she replies that this is the Institute of Literature, and brandishes a complimentary brochure presenting in four-colour format the diverse programmes offered to the public by the Institute. None of the programmes, though, seems to offer much hope of answering the question of Greek Architecture and where it might have come from. So we ask this officer: Does the Institute have a Human Resources Department?

Indeed it does. What type of position might we be seeking?

Directorship?

Filled, unfortunately.

Librarian?

Very doubtful that such a position would be coming up in the foreseeable future.

Building Maintenance?

Ah!

The Maintenance Department is in the rear, through a little door beside a large delivery entrance, both leading to a loading area, which is sweltering, as if all the heat unwanted in the rest of the building is dumped into this space, and where there is the incessant roar of HVAC monsters.

We’re hired, and issued our green overalls . . .