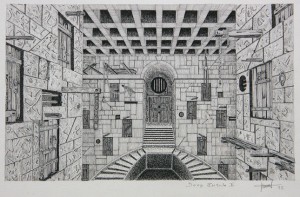

Artwork by Henri Souffay. Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery

By Bryan Patrick Young

This will kill that. The book will kill the edifice.

~Â Victor Hugo(1)

Architecture, like a character in Greek tragedy, has been haunted by Hugo’s prophecy: the printed text and its successor the digital, facilitating the word’s promulgation, assures the defeat of its rival. As demonstration, this essay will, like sacred drama, enact the ritualised death of architecture using fictional text as illustration.

The architectural historian Sir John Summerson laid down two conditions for the illustrator of architectural fantasy:

He must not lose sight of scale. Once that is lost or even rendered ambiguous, his drawing becomes incapable of communication in architectural terms. Nor may he employ forms which have not some reference (however slight) to our experience of executed architecture; otherwise his work departs altogether from the architectural sphere and must look for its justification either in qualities residing in itself or to its usefulness as a representation of some organisation which may be sculpture but cannot be architecture.(2)

These two conditions will be met in our essay, though its fantasies will be fiction, eschewing the usual procedure of illustrating architectural theses with drawings. Instead of the conventional entourage of architectural depiction, human figures, vehicles, trees, and background; fictional elements will be used, such as character, plot, and setting.

The proposed setting is an imposing edifice dedicated to the appreciation of fine literature. The main halls, there being nine, will correspond to the nine natural divisions of Literature:

Tales of Idiots,

Interplanetary Travel,

Dickens,

Rhyming Poetry,

Poetry that Doesn’t Rhyme,

Histories,

Sad Tales,

Translations from the Hebrew,

and The Occult.

The building will front a broad plaza for the festivals devoted to the literary arts, and parades, and for the performances that will be made by Living Lions. The façade the building presents to this plaza should be suitably monumental. Naturally the portico must have nine columns of a noble order, one for Idiots, one for Space Travel, etc. Each column will be carved, like Trajan’s column, with Pecksniffs, Queequegs, Glorianas, etc., and decorated in stunning colour. These columns will be the most celebrated aspect of the building, and portrayed on postcards on sale in the gift shop.

Naturally the Institute’s library has one of the world’s most extensive literary collections, and it is imperative that we reach it. Among that collection may be a volume, entitled ‘The True Source of the Three Grecian Orders as Shewn in Biblical Passages’, written by Cornelius Bainbridge, first published in 1784. How on Earth would the Institute of Literature come to possess the one remaining copy known to exist of this architectural treatise? It was owned by the architect Thomas Kneal (later Sir Thomas Kneal). It was given to him by a maternal aunt in 1919, upon his induction into the RIBA. No one knows where she got it from. Kneal on one occasion suffered so much ribbing from a colleague, Clarence Hiscox, for displaying the quaint and preposterous book on his professional shelf, that the next time he was visited by members of the International Style, fearing Hiscox would draw fresh blood by ridiculing him before the other Modernists, Kneal furtively shoved the guilty volume into the hands of a surprised housemaid, urging her to get rid of it. She in turn, not sure what to do with the book, tried hiding it among Mrs (later Lady) Kneal’s detective novels. But its title looking most conspicuous, she covered it with the dust jacket from ‘The Mystery of Black River Road’, by F. Glover. She was careful to note both title and author in her diary, in case her master should have occasion to demand the book’s return. As we have no information that Kneal ever did, we surmise that ‘The True Source of the Three Grecian Orders as Shewn in Biblical Passages’ remained in his wife’s collection of novels, incognito, when that collection was donated to the Institute.

Now, although Cornelius Bainbridge may have been a crank, and his theories of the origin of architecture dusty to say the least, we know that in the support of them he had the opportunity to take measurements of a number of monuments in Mesopotamia that sadly are now because of pillage and war no longer extant. This knowledge must be brought to the light of day—It must be brought to the light of day by us. For who but we would make judicious use of it?

Angus Hatter?

Certainly not Angus Hatter! Not that firebrand, whose ‘Finding Babylon: A Structuralist Approach’ was an excuse to libellously attack rival scholars and calumniate their theories. Certainly not Angus Hatter, whose belligerent diatribes against our research methodology are unequalled in the annals of academic feuds, and who declared that there was no proof for our conclusions, and never could be a shred of evidence for such lunacies! He shall be proved wrong! Yes, and to such a feverish pitch of excitement were we raised, staring at that page in the housemaid’s diary, with the name of that author and that title painstakingly printed in her childish hand, that our fingers twitched, and we momentarily lost all sense of professional decorum, and did something that we should not have done. We tore out the page. How it seared our fingertips as we folded it and stuffed it into our pocket. And how, stealing from the room, we jumped when the elderly lady offered us iced tea! Nothing could be permitted to detain us, for the guilt was written on our face. We fled from the house like Judas from Christ.

Did Angus Hatter see that page? We never stopped to ask. Is he before us or behind us in the search? The gnawing question torments us as we glide up the Institute’s escalator. We make enquiry at the Information Desk. Behind the smiling face of the officer is a sign stating: Every Question of a Reasonable Nature Answered Courteously. So we ask her: What is the true source of the three Grecian orders? Her smile not diminishing by a single watt, she replies that this is the Institute of Literature, and brandishes a complimentary brochure presenting in four-colour format the diverse programmes offered to the public by the Institute. None of the programmes, though, seems to offer much hope of answering the question of Greek Architecture and where it might have come from. So we ask this officer: Does the Institute have a Human Resources Department?

Indeed it does. What type of position might we be seeking?

Directorship?

Filled, unfortunately.

Librarian?

Very doubtful that such a position would be coming up in the foreseeable future.

Building Maintenance?

Ah!

The Maintenance Department is in the rear, through a little door beside a large delivery entrance, both leading to a loading area, which is sweltering, as if all the heat unwanted in the rest of the building is dumped into this space, and where there is the incessant roar of HVAC monsters.

We’re hired, and issued our green overalls . . .

. . . To serve, like the rightful prince in retainer’s clothes, the usurper on our throne.

Late at night in our magical green jumpsuit we can go everywhere. We have security-card access, and more importantly our mop and bucket that evince our right to be wherever we happen to be in this literary warren. Up to the floors where the writers toil far into the night, each in a cubicle arranged nearly as possible like a garret. These cubicles are arrayed in a vast multi-storey ring, so the writers can look across at each other, and see who is pecking away, and who is staring into space while picking their noses. At the bottom of the well is a large pool, known as the Writers’ Pool. There is an island in the centre, to which tour groups are rowed, so they can gaze up at the authors and wonder at the Birth of Literature. From time to time writers leap to their deaths into this pool.

Where to next in this great factory of words? The Institute has a Publisher, and a Ballroom, and a Printer where the triple-expansion reciprocating engines of the presses pound the night away like pre-Adamite monsters. Elves package up the brand-new volumes, and then they travel by roller coaster down to an enchanted forest, which is the Bookshop. There is also an academic wing, where the learned debate the relative merits of the literary output of the Institute, and locate the works in their theories. Finally, all the books wind up in the great Library, where so many of them are forgotten and are heard from no more.

The Library is windowless. This is to protect its priceless collection. The Library is enormous. It is about the size of a hangar for a fleet of 747s. But there is nothing cavernous about the Library, for it is nearly solid paper, cloth, pasteboard, and ink. The stacks are vast, and their weight is prodigious. They hang from rails of carbon steel, and despite being counterweighed, the motors to move them are the size of megatheria. The stacks are compressed against each other so the Library is like one enormous book comprising all the volumes of Literature. The only space in the Library are vertical slots required for the folding catwalks and ladders the library clerks use to access the innumerable rows and columns to retrieve the books as they are called for. These clerks are young, nimble, and agile. They have to be, living the life of spider monkeys. And they have to be sharp. A few tragic accidents have occurred. Crossed messages, a momentary confusion, and an unfortunate clerk has been caught between two stacks as they have been activated, and flattened into a raspberry crêpe. The impatient scholar, tapping a foot, instead of receiving the volume that was demanded, ends up being dragged into an unhappy scene involving security staff, ambulance personnel, and hysteria. Then as well, to minimize the damaging effect of oxidation, which would destroy the precious leaves, the air in the library is maintained at somewhat stratospheric levels, so the clerks are encumbered in having to wear oxygen masks.

With our access card we let ourselves into the glassed-in control booth, where the stack operators work during the day. Each operator, rather like an air-traffic controller, is in charge of five clerks. The clerks wear electronic devices at their waists, so the operators can track their movements on their screens. Oh, they are quite friendly, these operators. We’ve come to know them quite well. Amused at first at a lowly caretaker taking an interest in their tasks, they came to see it as a compliment, and were happy to show a little how the system works. A little here, a little there, and pretty soon you know the whole set-up.

Sometimes they don’t turn off their computers. They should; the locked door of the control room is insufficient security, but a few of them, in a rush at the end of their shift, neglect to do so.

- Glover

We tap the name, and depress enter. Our heart leaps as a column of titles runs up the screen. F. Glover was prolific! But where is ‘The Mystery of Black River Road’? Not there! That can’t be. They must have failed to catalogue it. It must be here. At random we click and highlight one of the other titles, and depress enter.

There is a distant shudder, a whir of machinery, and the booth begins to vibrate. The vibrations travel up our legs. Even the fillings in our teeth are vibrating. We feel through the floor the rumble of the stacks as they roll, ponderous as loaded freight trains. Wheels squeal, a piercing animal-like scream, cut off suddenly as with a resounding crash the stacks collide, succeeded by an abrupt silence. Then another motor starts up, and other racks are put into motion, and clash together. It’s like hearing an orchestral piece performed in Hell. It goes on and on as we wait with racing heartbeat. The gargantuan movements occurring deep within the library are invisible to us, like the drift of the continental plates, and we have nothing to stare at but the cursor of the monitor winking at us like a star unreachable in another galaxy. The Library is a colossal three-dimensional puzzle, and the computer is working it out. Finally there is the clamour of catwalks dropping into place, and morgue-like silence at last. We don oxygen mask and enter the Library through the airlock. No sound. No life. We might be on the Moon.

Up into the canyons, scaling the cliff-like stacks; were we to fall into the gloomy depths . . . certain death! The Gs are reached! Gilmour . . . Glass . . . Gledhill . . . Glocke—So many forgotten authors! O thou duplicitous siren, Fame, that so many ardent—Glover! B. Glover . . . F. Glover! ‘Boderick Mill’ . . . ‘The Colonel’s Mistress’ . . . ‘Dinner at the Vicarage’ . . . ‘Horace Gray’ . . . ‘The Portuguese Dowager’ . . . Where is ‘The Mystery of Black River Road’? Anguish! We pull the books out madly, open them, dash them to the ground. Cursed novels every one of them, not one of them useful in shewing the true source of the three Grecian orders.

As one half blind we stumble back down to the control room. There is a simple mistake. A simple mistake. She must have put down the wrong name. Stupid girl! We pull the diary page out of our pocket, unfold it, and stare at it and stare at it. But it says what it has always said. ‘The Mystery of Black River Road’, F. Glover. How can there be an error? But what’s this with the G? Staring. Is it possible—has someone doctored that G? Did it start out life as a C?

Jumping to the keyboard, we punch in F. Clover, and depress enter, our breath suspended, heart drumming like a woodpecker. F. Clover comes up. ‘The Mystery of Black River Road’! A thrill of joy, followed by ice chills down our back. Someone altered that letter. Deliberately. Someone deliberately altered that letter. Tampered with the historical record. Who looked at the diary before us? Who would be insidious enough, or capable of so degenerate a crime against scholarly . . .

Angus Hatter!

Oh! Make it not so.

Once more we depress the enter key, and with a distant rumble the stacks begin again their gargantuan deck-shuffling, knocking up against each other with cataclysmic thunder. The suspense is awful. Then all falls silent. We re-enter the library. Up into the Cs we climb. Clemens . . . Clohesy . . . Clover! We are filled with dread. If the book is not here . . . but what’s this we’ve tripped over? Like a bathmat. Like a rug that nobody’s bothered to straighten. No, more like a giant pancake with strawberry filling . . . How sad. Some poor unfortunate clerk, pressed just like a flower between the pages of a book. How long has he lain thus?—or she? We peer down. The head has been flattened like a ball of pastry dough rolled out, face seen in frontal and profile simultaneously, like, we can’t help thinking, a portrait by Mr Picasso. In the moment of crushing agony, the oxygen mask had slipped off. Then recognition triggers, and our heart lurches. Angus Hatter! We confess it, a moment of perverse and wicked elation, but that is followed by reeling horror and a feeling like a live rat in our belly trying to claw its way out, for beneath what remains of the hands we see a book. He had pressed it to his breast as though he would have protected it from the murderous force. Now it has been mashed into a single leaf, layer upon layer of text melded into one, and ironed on to his breast, a whodunnit never to be read again, beyond the few letters still visible on that dissembling dust jacket, including the fateful C for which the victim gave his life:

The Myste

Black Riv

<><

F. Clo

- Hugo, Victor. The Hunchback of Notre Dame. 1831. Trans. J. Carroll Beckwith, 1899. London: Collins, 1953, p. 163.

- Summerson, Sir John. Heavenly Mansions and Other Essays. 1949. New York: W. W. Norton, 1998, p. 111.

Bryan Patrick Young was born in Toronto, Canada. He holds degrees in Environmental Science and Architecture. In the past he has traveled through Canada, The United States, Argentina, Europe and Japan and now he resides in Mexico. His interests include philosophy, literature, architecture, art, urbanism, history and long-distance bicycling. His short stories have appeared in a variety of Canadian, US and UK magazines.