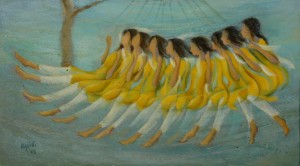

Artist Work 261 by Jamil Afridi. Image Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery.

Suresh, the sweet talking three-wheeler driver was also known as ‘mage aiyya’. It generally meant ‘my brother’ in Sinhala, but if you thrive on a slim desire for fat men who craved sex and love in awkward places, it never felt any better than something forbidden, something wrong, like ‘daddy’ in America.

So, they wouldn’t call him Suresh. This was a fact they turned out to live. It grew into a tree and stood stone-still right at the corner of the Colpetty Junction. It was believed that he inherited his father’s belly heavy as a cricket ball and the shoe-brush stubble clinging under his double chin. The men around his area watched him keenly, closely, impolitely. The way he devoured those women who called him ‘my brother’, fleshy and middle-aged, smiling so loosely, saying little, wearing less.

“From now on I’m going to cover my face or hit it against the wall. I’m sick of seeing this pimp, machan!†Perera’s mind, which never remained quiet, starved by a drought just thinking about it, returned to his cigarette; the ashes falling harmless at his feet.

“What for? It’s better to witness than wince.â€

The afternoon baked without regard. It was the curse of a neglected oven. Foreheads the colour of beach raved, sweat crowning broadly. He went on in one breath and no one would interrupt. “But how does he charm those cheap skirts? What kind of game does he play with that bat of his? To strike all fours and sixes, Nihal?â€

His eyes dilated, his tongue wiggled ready to spring. He liked this about him. He always thought a chance would come when at this moment all he could do was reel and return to a lifetime’s worth. The fine Hindu sixteen year old who flung a charm in the prime of 1974. He had felt the strings of his puppet being pulled. Leaning against the poster defiled wall, he’d have his sleeves neatly folded up to the elbow, shove a hand deep into his pocket, wait where the nerve teased and tore by the bus stop, plow ahead inch by inch following her on tiptoe the instant she spilled out of school, who, in turn giggled into books with sudden softness if he winked. How the sky matured like plums, how silence lay between them like a bed, how this vandal youth studying her from careful distance graduated to libertine aching to prick and profess, how the white uniform traced her bra-straps faintly visible, how her braids reeked of Sunsilk shampoo.

How today, Suresh’s niece smells of Sunsilk. Today he heard her shriek like window glass smashed to the blow of an impending leather ball. He rushed out of his sister’s shack a day after this as though the sun could heal it all when it was too late. Each time he revoked mid-word, she convinced with a quick snapping that it wasn’t a teenage imagination. Earnestly now, the thin of her lips straightened.

Podda, you’re sure?

She’d stop sweeping the floor, tilt up a chin familiar as his, and shoot a tear-stabbed gaze at him while the fan blades above her casted shadows that won’t go away. Like the strips of sun streaming from the clefts of a takaran roof.

Yes.

Then he knew there was nothing to mend over what was done. The damage was beyond repair; it creamed over his head. The yes yessing, taut as a bowstring, echoed for requital. Then he knew this was why he never maintained a wife but he was always a brother. He would always be as long as he let it ooze from his fingertips and bleed like brickwork, hot and viscid. As long as it drummed and roared inside him, nauseous. As long as he could spit on the ground, bear the angry sky and strike him in the face.

Rushda Rafeek is currently based in Sri Lanka. Her poems and fiction pieces have been published in various print and online publications including The Rumpus, Vayavya, Monkey Bicycle, Cyberhex, Mandala Journal, ARTRA, Inspired by Tagore, among others.