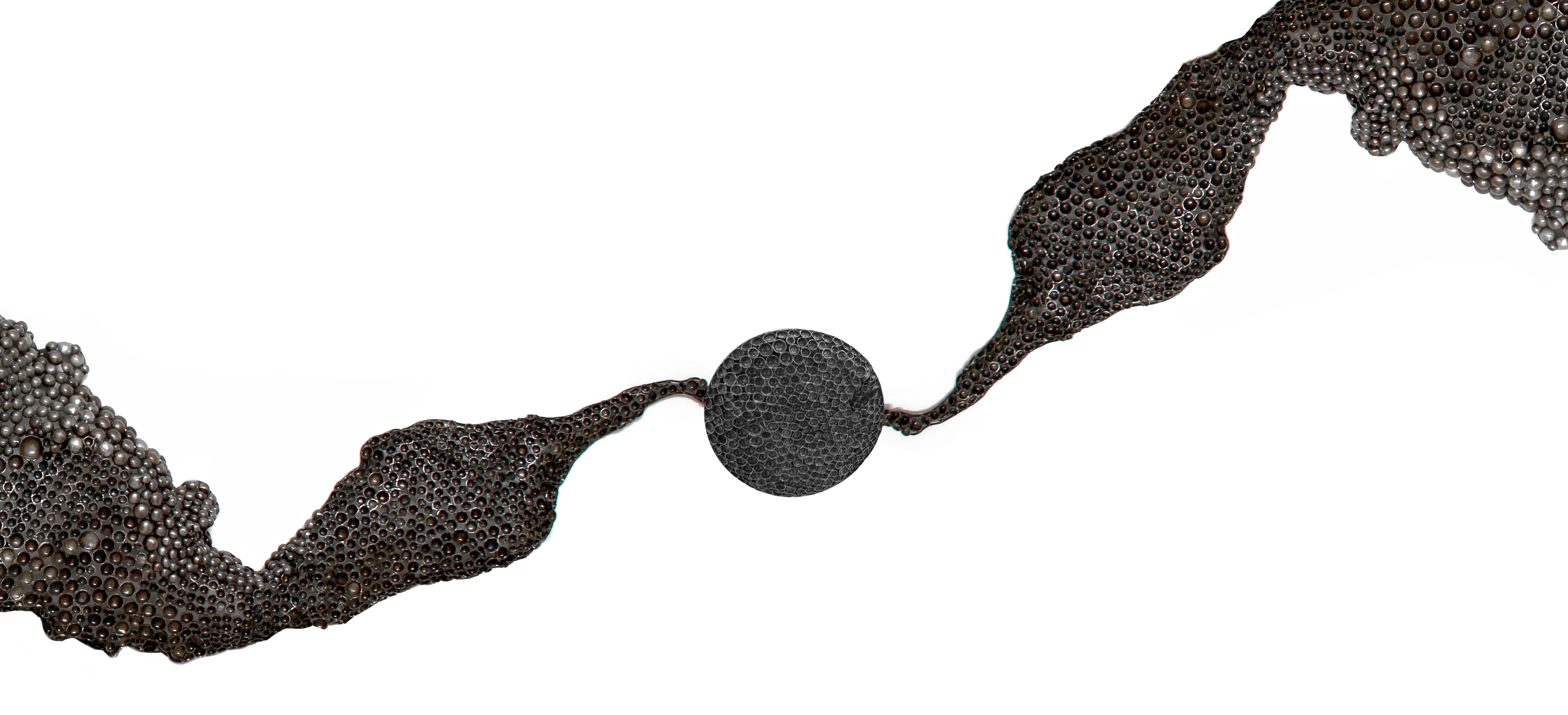

Creation of Earth by Abdullah Qamar. Image Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery.

I was Dorje Phagmo. I don’t remember being anything else; my teacher and the lamas recognized me when I was nine months old. Childhood was pure joy; my teacher was always near. She was strict but I was greatly loved. My birth mother visited often, and the anis were fifty-nine more mothers to me. Samding nunnery was some distance from Nagarsi on the trade road between Lhasa and India. We had a fine statue of Buddha, but we were not a rich nunnery. Many women made pilgrimages to Samding and sometimes travelling lamas stopped but we did not encourage visitors. My immediate predecessor despised the traders who detoured to Samding to worship. She retreated to the meditation cave high on the mountain. When the philangs invaded with their guns and shiny buttoned coats, and asked to make her acquaintance she was sure to be “in retreat.†The abbot of Palchor Chode sent word that the English did not come to steal, they wanted to learn about our history and practices. But she did not believe him. Later the Abbot came, himself, and said they did not believe a woman who was never in her rooms could be as important as he told them she was. She laughed and said she did not believe they were as important as the abbot thought they were. They had come but they would not stay as other invaders did not. She said that and I believed no one would ever dominate out mountain high country. What did we know? The anis were peaceful women, worshiping peacefully.

Our lives were quiet and worshipful. We lived high on the mountainside but trees flourished because they were tended. How I loved the apricots! I called them little suns, and they tasted like the sun. I suppose sometimes I was petulant and impatient as a child is likely to be but the love that surrounded me was higher and stronger than the mountains that filled our world. The glacier cold was never a part of my world.

My own, that is my distant ancestress’s, story of how she attained the name Dorje Phagmo, was told to me from before I could remember it. The name means

In the early 1700s the Jungar Tartars–Mohammedan warriors–were bent on conquering and converting all of Asia. They invaded Tibet and laid waste to monasteries, killed lamas and anis and stripped the gold from our gilded Buddhas. Those at our nunnery thought we would be overlooked because we were hidden from the regular tracks. But that was not to be. One day the farmers and villagers came and begged us to hide, as they were going to hide. They knew the invaders would burn their homes and our nunnery and the nearby monastery. The story of Tartar ruthlessness had spread through the land. But I–for I am my ancestress as my teacher always told me–refused to abandon our home. It was the only home most of us had ever known. My teacher had become a very old woman; she had taught me the power secrets that she, herself, had eschewed, powers a teacher will not need but that an abbess may need to protect the anis in her care. I do not know just what I did, for in this life, as I will tell, I was only a child and had not been taught all the scriptures and none of the deeper secrets.

The Jungar Tartars arrived at the gates on their horses with silver on their bridles and long steel swords in their hands, long black beards and booming voices. They demanded we open but they got no answer. They broke down the gate and found the courtyard full of pigs gathered around the largest, angriest, snortingest sow they had every seen. Swine and dogs are so abhorrent to these Mohammedans that they turned their horses and rode away even faster than they had come. I loved that story and always felt myself, the Thunderbolt Sow, Dorje Phagmo, huge and powerful and wonderful in my protecting anger. As a child I practiced snorting, delighted when the anis and monks pretended terror and then doubled up in laughter and my snorting turned to giggles.

I was still almost a child, fourteen years old, when the Red Guards came to Tibet in 1961. My teacher had taught me the scriptures and prayers but I was still learning the basics; I had not matriculated, fully earning my title, those lessons would have taken ten more years. Teacher had heard from the peasants about the Chinese in Lhasa and that the Dalai Lama had fled to India. All of Tibet, even all of China, was overrun with angry young men who, like the Jungar Tartars, burned and destroyed. The monks warned that if they came to our almost hidden monastery they would rape and murder and destroy. The farmers, always our friends, told me to hide in the meditation cave high up near the mountaintop. They promised to provide what food and milk they could. The cave was hidden among bushes and boulders. Once I had remained there three months, three weeks and three days meditating. I had no fear of being alone. But I was grateful that my teacher came with me because she wanted to teach me whatever power secrets she could, for she was growing elderly and frail and her aim was to equipment me with what skills could save me if I were not killed.

We often heard the drone of airplanes seeking out places like ours. They were determined to destroy every remnant of Buddhism in Tibet for their godless Master Mao. Farmers were nearly starving but they came, only at night, for fear of being seen from the air, to bring a little milk, a little tsampa—roasted barley flour – some tea. Anything to keep us alive. They wanted to show us how to snare birds that we could cook but we refused to eat any flesh.

My teacher taught me how to warm myself even in the winter blizzards, and how to conserve my energy so I could live on the small amounts of food so we needed little from the mostly homeless farmers who made shelters of tree limbs and had hollowed out other caves. My teacher taught me to leave my body at will. She said if I were tortured and raped I could rise above my body and feel little of the pain. She said there were many other power secrets but I was too young and she was too old. She had very little strength and such teaching demand great strength from both teacher and pupil. A few days before she died, she said she was so old and such a poor dried husk of a human that she could not cry the tears she wanted to cry for me. She said, “You will not forget me as I will not forget you and some day we will be together again—I in a younger body, you far wiser.â€

She died and the people who brought food insisted she must be taken to the one lama who remained in the village disguised as a yak herder. Devout and loving people cannot be compelled to disrespect someone like my teacher so they gathered and prayed. But a boy, who had been promised rewards, told the Red Guards who were using our nunnery as a garrison and a jail. He had seen, not often, but a few times, the people who brought me food. The brown clad soldiers came. They were prepared to rape me, but when they stripped off my robe they saw my bare head and all my bones visible just beneath my skin because I had so little food. They saw not a woman–certainly not a fierce sow–but a childlike skeleton, more frightening than tempting.

They took me to the capital to their captain. He send me to prison with all the other anis and monks. He did not know my story and no one would have told him. I was in jail three years. When the others discovered Dorje Phagmo was with them, they shared their meager food with me. I did not want to take it for I knew I could live on less than they but it was their only possible act of worship. It was both very bad and perhaps good for me. My hair grew, long and wavy and my body became as it had not been before. I became beautiful, or so everyone told me. The guards told the new commander of the city who came to see this miracle in the prison where people were dying of starvation and of their beatings and tortures and I, like a wildflower among the stones of the barren mountain, had become beautiful. The guards had raped me, but I was not in my body when they used it for disposal of their semen. Practicing what my teacher taught, I felt as if she were in the filthy prison with me, helping me remember how to find the space in my mind that let me float away from the resisting body.

The commander took me for his own. He locked me in a room in his quarters where I was fed well and dressed in clothing I had not known existed. He insisted on using my body many different ways. He became angry that I seemed a doll and not a woman and beat me when I did not respond to him. He was a bad man, an ugly man but a man who loved the beauty of my body–an idea I almost understood. I learned to respond to him. I learned that my body could feel pleasure. These strange ideas invaded the times when I sat alone in my small room and meditated. I remembered being held and caressed when I was a small child and that I had watched the sow we kept feeding her piglets, grunting with some sounds that seemed to be pleasure. What would my teacher advise? I had no teacher. I had nothing but the Commander who caressed my body and stroked my hair and asked that I do the same to him. “Gently,†he said, “My skin is soft as yours is,†he said. “I have a man’s hard muscles and you have a woman’s soft breasts.â€

I was not Dorje Phagmo; I was Lotus Flower. I became a woman like other women but not like Tibetan women who were forced into poverty and servitude they had never known. I was like a few Chinese women, kept by the important soldiers. When I became pregnant the baby was strangled as soon as it was born whether boy or girl. One, two, three, four, five babies. I cried and shrieked like any woman would. I was not an ani; I was an ordinary woman, used as ordinary women are by powerful men.

I learned their language. I never, never told him the truth when he asked about my childhood. I spoke of helping my mother harvest barley and make tea. He wanted to take me to Beijing but I did not want to go. I became willful and spiteful and mean to him. I said I could never leave Tibet. He left me as a gift to the next commander. But I was not so beautiful then, my body was used and wear-weary, the new commander did not fancy me. He made me the caretaker of the other young women he favored. Now I was trusted to go into the streets and shop for food.

At first I was afraid but I longed to go into the holy Jokhang even though the Chinese stabled their horses in the courtyard. No woman was safe alone on the streets but I had a card to carry saying I was in the Commander’s household. I began to go into the desecrated Jokang where some precious images remained. In a dark little shrine there I met an old woman who had been an ani who began to tell me that women had once been strong. She told me my own story just as I had been told when I was a small child. She said, “She, of all women, was allowed to ride in a sedan chair.†I asked what a sedan chair was. She told me her mother once made a pilgrimage to our monastery. “We think she may still live. She was second only to the Dalai Lama in the hearts of the people.â€

I had learned not to cry, but I knelt with my head in that old woman’s lap and shook with sobs. She stroked my head as no one had stroked my head since my teacher died. “She may still live,†I whispered to the woman. I cried many nights. Dorje Phagmo had died and been reborn, even in the same lifetime, as Lotus Flower who did not recite the prayers, who sometimes longed for pleasures of the body, who had learned to be sad that she was ugly in the eyes of men.

I found others like this old woman, many had been anis, many had been in jail and tortured, many were toothless, some lame or deaf. I found lamas, old and bent and scarred from torture, many bitter and angry and ugly. Yet, just as I loved the old anis, I loved these old lamas. I decided to disappear from the city. It was not so hard to slip away. I had a sense that told me when I met older people who I could trust when I asked directions. I wandered, begging, letting my hair go wild, wearing rags, covering myself with dirt and charcoal. I told only one or two whom I came to trust some part of my story. From one I learned that my teacher had been reborn in India. She was now studying with her teacher, a lama who lived near Dharmsala; she was now over thirty years old. My teacher lives! For the first time I could remember I cried tears of joy. I knew I must reunite with her. She had been a mother to me. I felt a tether pulling me toward her.

I knew many Tibetans were finding paths over the mountains. Some paid men they called snakes to guide them. I had no money and I did not want to go with others. I wanted to walk alone, trying to remember the scriptures, softly chanting. A few monks and anis were allowed to live in the ruins of former monasteries. Not all were trustworthy, I had learned to read expressions and the shifting of eyes, the language of bodies. I was careful where I stayed but I stayed a whole winter with a tiny group of anis. I played the thigh bone horn and chanted with them. They asked me where I had learned to chant but I did not mention Samding except to ask if anyone survived. They spoke sadly about the dead Dorje Pagmo and hoped she would reincarnate although she had no home. Sometimes they saw tears at the edge of my eyes and held my hands.

In the spring I went alone, walking over the mountains, following landmarks I had been told were there. I walked at night and sometimes walked a short way with others I met who were escaping. When I met a soldier I raved like a crazy woman begging for a crust of bread to feed my long dead children.

I believe the strength of our age-old connection helped me find my teacher. She knew me instantly and I knew her. She was young and strong; she cried to see me old and bent and filthy. She lived in a small nunnery with thirty other anis. Her teacher lived in a monastery nearby. He did not recognized me. For five years now we have lived together in that holy place, but we have not told anyone this old ani’s story. I studied what I had not had time to study before. Strange to say, just as I became beautiful in prison while others sickened, here I am becoming younger as I grow older. My teacher’s teacher looked at me a long time one day recently. “Perhaps we met once long ago,†he said.

The time is nearing when I will tell the Dalai Lama my story. I will never ride in a sedan chair but I will return to the ruins of Samding, my home, and begin rebuilding with my old, bent hands. The Chinese will think I am a crazy old Tibetan woman. I believe the people will help me. I will minister to the people and ask for a sow in return for my prayers. The time will come when I will say, “I am Dorje Phagmo.â€

June Calender has retired from writing plays in NYC where her plays were seen off-off-Broadway and nationally. She now lives on Cape Cod, is writing a much researched book about a traveler to Tibet (1937) and also writes prose, poetry and memoir. She teaches writing at the Academy for Lifelong Learning and edits their annual anthology.