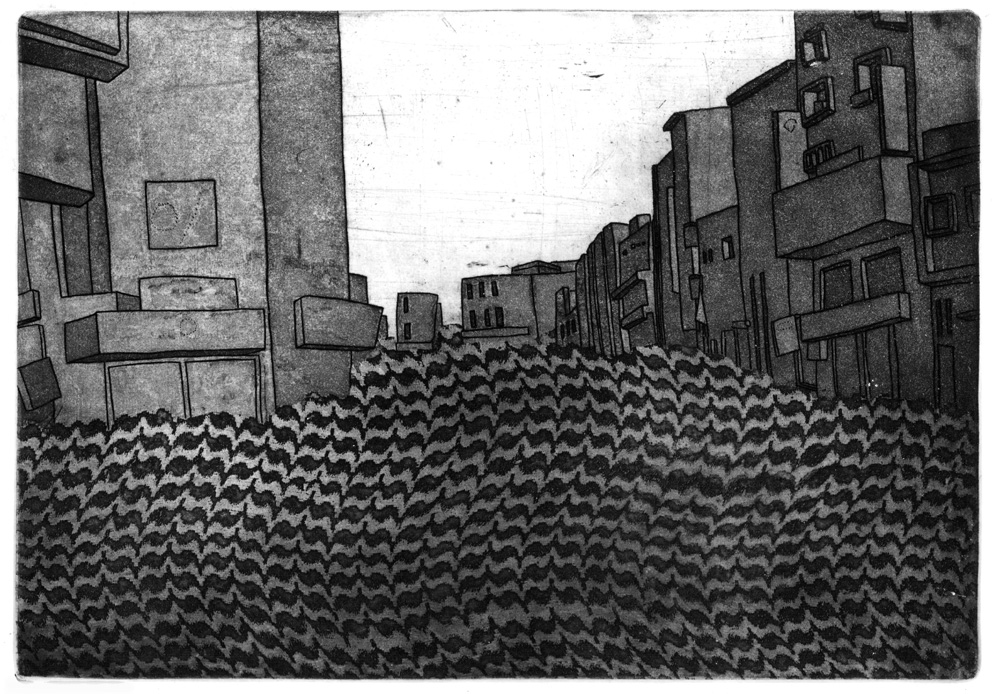

Artowrk by Atif Khan and Damon Kowarsky. Image courtesy of ArtChowk Gallery.

What the slutty city did to the Queen’s language (read part I here)

Some years back, when V.S. Naipaul was in Calcutta to launch his book ‘Magic Seeds’, he had wondered if the city’s residents really cared for their habitat. The general picture of neglect he saw in 2004 was at odds with his first impressions of Calcutta from 1963. On that earlier visit, Naipaul expected to be hit in the face with images of abject poverty and overarching sordidness — a city panting under the staggering weight of a never-ending stream of migrants who had spilled over from the slums, filling up its pavements, parks and other public spaces. In the essay ‘Jamshed into Jimmy’ (The Overcrowded Barracoon), Naipaul wrote:

“But nothing had prepared me for the red-brick city on the other bank of the river which, if one could ignore the crowds, the stalls, the rickshaw-pullers, the squatting pissers, suggested not a tropical or eastern city, but central Birmingham. Nothing had prepared me for the Maidan, tree-dotted, now in the early evening blurred with mist and suggesting Hyde Park, with Chowringhee as a brighter Oxford Street… Here unexpectedly, and for the first time in India, one was in the midst of the big city, the recognizable metropolis with street names – Elgin, Allenby, Park, Lindsay – that seemed oddly at variance with the brisk crowds, incongruity that deepened as the mist thickened to smog and as travelling out to the suburbs one saw the factory chimneys smoking among the palm trees…â€Â [1]

Most of the overtures made to potential investors, and the many memorandums of understanding signed between the local government and the so-called entrepreneurial giants from abroad, were never translated into anything tangible. The only development that Calcutta saw during those years of disproportionate focus on fast-tracking industrialization and enterprise — a trend that has since been accelerated after the Trinamool Congress took over from the Left — had to do with real estate. The realty developers and their henchmen who control Calcutta’s “promoter raj” have never had it so good since the Trinamool Congress came into power in 2012.

“Promoter” is a terrifying word in Calcutta, having more or less the same connotations as the “Mafioso”. Promoters are capable of having an academic arrested and made to spend a night in police custody, ostensibly because he bulk-emailed a cartoon about the state leader [2]. The real reason for inflicting such an extreme form of censorship on free speech could well have been that the housing society — from whose account the “defamatory” image was sent — had ignored the concerned promoters’ proposals to use their services. Promoters are often the most powerful people in the neighbourhood who might demand protection money, pitching it as a subscription for celebrating the festival of the goddess of learning, or as donation to renovate the local community hall. Then again they could be completely brazen and upfront about the demand. In return they might promise to “do a mutual”, i.e. mediate to solve a crisis to the best interest of two parties locked in a protracted battle over tenancy rights, deal with belligerent daughters-in-law or people tossing their trash in someone else’s kitchen garden.

Promoting of real estate continues on an overwhelming scale in Calcutta, flouting municipal regulations and ignoring environmental concerns. The all consuming hunger to tear down every stand-alone family residence and erect a block of flats in its place has a direct and visible impact on Calcutta’s changing demography. The city’s middle-class (significantly different from the affluent, materialistic, Tory-supporting middle-class we read about in the novels of Alan Hollinghurst or Zadie Smith; the Calcutta variety has less money, greater cultural pretensions and an opinion on everything under the sun) cannot afford to rent or buy property in the areas they have traditionally lived in for years. Leaving their familiar neighbourhoods in Bhowanipore, Park Circus, Shyambazar and Lansdowne Road, the younger generations of salaried people and small independent business owners get pushed towards the city’s fringes, looking to find a space in the undistinguished apartment blocks built on landfills and rice fields off the Eastern Metropolitan Bypass.

New constructions in the city — often featureless, rectilinear beehives built inside gated compounds — are frequently christened as a “court”, “manor” or an “enclave”. The colonial sensibilities evident in the nomenclature extend to pretty much everything else about these antiseptic spaces, cordoned off from the filth, sweat and territorial stray dogs on Calcutta’s streets. A manor in Calcutta today is indeed much like its original medieval European version, completely self-contained, having its own built-in supermarket, school, bank, parks, gym, spa and theatre. It’s also totally impregnable, well fortified against petty burglars and the intrusive of door-to-door salesmen that stand-alone, unmanned establishments are exposed to. They are watched by surveillance cameras and an ever-vigilant 24-hour security team on shift duty. Likewise, a cluster of apartment blocks going by the name of an enclave could indeed be surrounded by a completely contrasting and alienating terrain — a crescent-shaped stretch of inundated rice fields, for instance, or even an intensely-knit phalanx of hay and asbestos sheet-covered structures in a slum.

The jarring incongruity of colours, material and design in Calcutta’s architecture — the crude juxtaposition of slums, shining new high-end multi-storeyed apartment buildings, and the early 20th-century affluent homes with their rain-darkened Corinthian pillars, festooned keystones, and missing slats from the green French windows — accentuate the “jagged” nature of the Calcutta skyline that Nirad C. Chaudhuri had written about. While the terraces of the new residential buildings inside gated compounds are spotless, the spare stuff people of an earlier generation would accumulate now end up on the street, spilling out of the municipality-designated open enclosures, too inadequate and too few to contain the volume of waste generated by the city’s 14.5 million residents. The sea of fruit peels, Styrofoam containers and non-biodegradable plastic wrapping in dirty neon colours accumulating on the approach road to some of the city’s most high-end shopping malls is just one example of the Calcuttans’ willingness to accept the beautiful and the damned in the same frame, as long as the latter is kept on the other side of the sterilized glass door. Calcutta’s streets today are its new rooftops, where people freely chuck the things they do not want any more. And it is extremely unlikely that anyone treating the streets like a never-ending quagmire would be made to “swallow a case” (get booked by the police) for committing said offence.

Incidentally, there are only a few things a Bengali-speaking Calcuttan would not ingest. From the “traffic signal”, which bus drivers ‘eat’, i.e. linger at deliberately, trying to pick up more passengers, to a ‘half-sole’ (meaning a rejection that a poor, lovelorn bloke must gulp down with the humiliation of being turned down) — the omnivorous Bengali seems to have an appetite for just about anything except criticism and household furniture. And “eating footage” (a metaphor borrowed from cinema shooting in the pre-digital era, chastising the tendency to take a long time to come to the point even as the camera keeps rolling) is a thing the Bengali-speaking people do a lot, being generally pre-disposed to deferral and circumlocution.

Several years ago, as an undergrad, I played a cameo in ‘Much Ado about Nothing’. A couple weeks into the rehearsals, almost everyone involved in the production had internalised a tendency to play on words. The most prolific punster was the play’s director, Samantak Das, who had re-christened Kolkata, as we call my hometown in Bengali, ‘Coal-cutter’. It was a reference to the city’s overall soiled look. As anyone reaching Calcutta by train would notice, the skies change colour about half a kilometre away from the terminus, as if one were viewing it through a semi-transparent, slightly threadbare georgette scarf that has not been washed in a while.

Coal-cutter was an accurate and visually-compelling way to describe the sooty city. The term invariably brought to mind cookie-cutter houses — an image of which Calcutta’s bewildering mix of inverted wicker basket-like pavement dwellings, vertical townships, chrome-and-glass commercial structures and crumbling colonial mansions was the polar opposite. Cuteness was never Calcutta’s thing.

A year and a half after Much Ado we put up another play: T.S. Eliot’s ‘Murder in the Cathedral’. Some of us playing the chorus would try to imagine a back story about the women we played — the sort who had known both “oppression and luxury”, been exposed to both “poverty and license”. The cues seemed to point towards a slightly dubious side in these women. I remember asking the play’s director, Arunava Sinha, if it might not be valid to imagine those lines spoken by a hag, delivered quite suggestively in remembrance of the good times she had known before she became an old whore.

It seems to me the careworn hooker past her prime I had imagined then, might in fact belong in Calcutta’s streets now as much as she would have in a brothel in Canterbury in 1170. I like to call her a “Randi/y Coal-cutter”. To me, the idea denotes both the city as well as one of its most generic emblems — the figure of the woman whose natural good looks and acquired fine taste have been mauled, mutilated, torn apart and painted over with cheap, corrosive makeup. She could have been filling up an exercise book with poems on a lazy afternoon under a slow-whirring ceiling fan, or even starting a revolution, but has been made to solicit in the marketplace instead. Successive governments have wooed potential investors from other states in India and abroad and almost always ended up with promises that fell through along the way. Calcutta seems to preclude the idea of a serious courtship.

“Ugly-beautiful”, “filthy-gorgeous” (as the New York Times [3] called her in a photo essay a couple years back), Calcutta used to be a product of metropolitan aspirations. The urban impulse though has been rather inconsistent, evident only in fits and starts. It was on display at the very outset when Job Charnock rescued a young widow from being burnt alive on her husband’s funeral pyre and set up home with her in a new world — the nucleus of what would evolve into the city of Calcutta. Much later in 1983, when people stood in ankle-deep water outside a gallery in Calcutta in peak monsoon season to catch a glimpse of sculptures on loan from the Rodin Museum in Paris, it was the same respect for cultivation, inclusivity and liberal thinking at work.

The tides seem to have turned since then, dragging the city back to its provincial core, taking her by the hair like the Kulgacchia villain if necessary. The tendency to deface, paint over and obliterate the traces of urbane elegance and cultivation that, let’s face it, was introduced by the mercantile and well-travelled British to an intrinsically-agrarian and sedentary, essentially laid-back and therefore insular culture, is here with a vengeance.

Calcutta finds itself in a peculiar conundrum. Its heritage structures must either suffer gentrification — demolition to make way for development covered in a powder blue coat as part of a full-on drive towards a forced homogenization of the cityscape — or be pushed to a state of accelerated decline. Looks like a basket case to me, or, as we say in Calcutta, “What’s the case?” a rhetorical question, meaning, “What’s up?” to which the rehearsed answer is “suitcase”. The provenance of this gem, as my friend, the artist Koeli Mukherjee Ghose, reminded me the other day, might lie in the disgraced stock marketeer Harshad Mehta’s claim in 1995 that he paid Rupees 1 crore (10 million) to then Indian Prime Minister Narasimha Rao to bail him out of the securities scandal[4]. Mehta said he had sent across the graft money to the PM’s office in suitcases. “Suitcase” in Bengali speech has since come to denote being in deep trouble with no apparent solution in sight. It’s like a magnified Pandora’s Box meeting a pretty kettle of fish, and infinitely more complicated and sinister than the two put together.

Traditionally, the Bengali-speaking people of Calcutta have turned to English in moments of crisis. They have invested English words with quaintness and immediacy, and, in certain cases, a degree of weirdness, creating a parallel English vocabulary that few people from Britain would have any clue about. This is Randy Coal-cutter’s way of throwing the English education it was made to receive since 1835 right back at the mighty Empire.[5]

Chitralekha Basu is a writer of fiction, translator and singer of Tagore songs. Her book, ‘Sketches by Hootum the Owl: a Satirist’s View of Colonial Calcutta’, was published by Stree-Samya in 2012 with a foreword by Amit Chaudhuri. She is also published in The Caravan magazine and Asia Literary Review.  She is writing a series of essays for China Daily. She lives in Hong Kong.

[box title=”Endnotes” style=”soft” box_color=”#9a0c0c”][1] VS Naipaul, ‘The Overcrowded Barracoon’; Vintage, 1972.

[2] Jadavpur University Professor Ambikesh Mahapatra was arrested and spent a night in police custody after he bulk-emailed a cartoon on West Bengal chief minister Mamata Bandopadhyay in April 2012.Â

[3] New York Times, November 16, 2011.

[4] Dilip Bobb, ‘Fact or Fiction’;Â India Today Magazine, July 15, 1993.

[5] British educationist Thomas Babington Macaulay proposed replacing instruction through Sanskrit and Arabic with English in India’s school in his ‘Minute on Indian Education’ in February 1835, which was brought to effect soon afterwards. Bureau of Education. Selections from Educational Records, Part I (1781-1839). Edited by H Sharp. Calcutta: Superintendent, Government Printing, 1920.

[/box]