“I’m not here to confess, Father.”

“What?”

“I’m not here to confess–“

“Chuy?”

“Yes. Listen to me. I’m here to warn you. You have to listen to me.”

“I don’t need to be warned, Chuyito.”

“It’s now, Father! It’s tonight, after the Mass. If you go now, you can still get away. You can’t go home after the Mass. Do you hear me, don’t go home!”

“Chuy–“

“No, Father! God put me there. I saw the Scientist, I heard him say the words. God put me! This is what I was made for.”

“Chuy, if I don’t go home tonight it will be tomorrow. And if I don’t go home tomorrow it will be the next day, or the day after that. I won’t run, mi hijito. This is what I was made for.”

“Father– please!”

“‘The Son of Man did not come to be served but to serve and to give His life as a ransom for many.’ Am I better than Our Lord, Chuyito, that I dare to hope for a different fate? The blood of martyrs is the seed from which the Church grows.â€

The boy groaned. He could hear Father Chuy’s voice, calm and patient, as if he were explaining something to a child, but the words sounded far away to him now, incomprehensible. The boy burst blindly from the confessional and stumbled out into the night. It was darker than when he went in, and colder. At the edge of the field he lurged forward and vomited, then, wiping his mouth with his sleeve, he began to run. He ran away from the church as he’d run toward it–could it have been only minutes ago?–but wildly now, through the field of weeds, recklessly and without purpose. Unheeding of the voice calling his name behind him.

*****

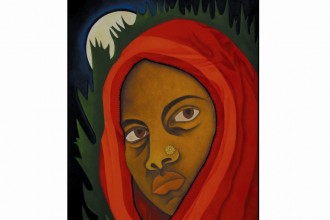

Like León’s one snowfall, afterward, Father Chuy’s death took on a legendary significance. In the months after their priest was buried in a plain white cassock, his restrained energy at rest at last, there were those who claimed he’d appeared to them. Little Gilberta saw him under a palm out back of the church at twilight, a wistful smile on his face as he looked up at the stone building. He came to Don Ramiro in a dream and cured his angina. Unless a grain of wheat falls to the earth and dies, he told Doña Agustina, it cannot bear fruit. It was one of the passages he’d read that night, the night he officiated his own requiem. That Mass at the Sagrada Familia was at the center of the legend. Weeknight services were usually sparsely attended, a score or so of the palsied and pious, yet it was difficult, afterward, to find anyone who hadn’t been there that Monday. They told how Father Chuy wore a blood-red chasuble, not the purple of the liturgical calendar, and how his voice rang out as they sang, a cappella:

Into Your hands

I put my life, Lord.

Into Your hands

I give myself to You.

I must die in order to live,

And my life is what I give…         Â

For the first time in all their memory their priest, even more grave and solemn than usual, said a Mass all his own, not that of the Missal. No one read la lectura. No one sang the aleluya. Was he paler than usual in the candlelight? Did his voice tremble as he spoke the words, Whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for My sake will find it? Did his hands shake as he held up the Host before them? It was hard to know afterward what was memory, what imagination.

But of that Mass, the boy knew nothing. Not even the light emanating from the stained glass windows of the Sagrada Familia touched him where he lay, supine by the roadside in the field full of weeds, convulsed by agony and choking on his own hot tears, the handful of silver coins spilled alongside him like so many seeds in the fallow soil.

*****

On Friday the boy put on his red windbreaker and walked down the main thoroughfare to the Casa Municipal. He stood outside for more than an hour, hands in pockets, watching the branches of a big tree opposite toss in the wind, throwing dark arabesques on the pavement below. The rains were coming. He could already taste the wetness in the windy air and feel, like a vibration, the low rumblings over the cerro.

The boy didn’t go in. If he had, he’d have had to sign in at the lobby and state his business, and this was off the record. He waited, let her come to him. The boy knew how it worked from his evenings of reading under the great stone arch. Someone brought the car around front, and Barbi Botello emerged from the building. It was just a matter of timing, and the boy timed it right.

She looked, if possible, even more glamorous up close. For one moment, before her impeccably shadowed eyes and lipsticked mouth, her pushed-up breasts and tight skirt, the boy even hesitated, unable, in the fog of her perfume, to find the words he wanted. Women always intimidated him, and this woman in her forties was so self-consciously beautiful, so powerful and confident, that for an instant the boy stood dumbstruck. Then the words were back, spilling out of him, warm and liquid as the impending rain.

“Señora, there’s something you need to know. I can tell you where to find the Scientist. He lives here, in Guanajuato, just a few hours from León, up past the Cañada Rosal. He’s responsible for the death of Father Chuy of the Sagrada Familia. I could take you there– show you where he lives, if you want. I’ve been there…”

But as he watched the mayor’s face slide from surprise into amused condescension, the boy’s words tapered off, ending with a flat, atonal finality. “You already know.”

“Not at all!” Her tinkling laugh rang out and was met by the deeper laughter of the driver who stood alongside the black car, holding the mayor’s door open for her. “Listen, corazón, it’s just that it’s Friday. We all have plans. Why don’t you come back on Monday and we can sit down and sort all this out calmly?” One stilettoed heel was in the car even before she’d finished speaking.

When Barbi Botello had gone, the boy stood frowning after her in the deepening gloom until a loud voice startled him from behind.

“¡Ya, basta! It’s over. Go home.”

“What?”

“It’s over, kid. Who do you think pays the goddamn bills around here? I said go home.” The guard stepped down from his post and picked up a stone, holding it aloft menacingly.

“Chinga tu madre,” the boy growled, turning to go.

Almost at once a white-hot pain exploded in his right shoulder, the force of it propelling his body forward a step. He was turning around when a second stone caught him just above the eye, knocking him, disoriented, to the cobblestone. The boy lay for a minute observing the stone disinterestedly, its shape and contours, as if it had nothing to do with him. It was a perfect oval, smoothed into submission long ago by a river somewhere, so white it glowed in the twilight. There were dozens like it edging the little garden in front of the building like the gleaming teeth of a wide-mouthed monster. At once an image appeared in the boy’s mind–a vision, almost–of Saint Stephen at the moment of his stoning: the saint stood praying, wrapped in golden light, a rapturous expression on his face. But the boy clenched his teeth and shook his head against the image.

“God damn you,” he spat, enunciating every syllable with deliberate force. “God damn every one of you to Hell.”

Then, wiping the blood from his eye with the back of one hand, he struggled to his feet. Over the dark cerro, lightning danced erratically. A sudden gust of wind caught the flag above the building, whipping it wildly. It made a sharp flapping sound, as though the eagle at its center had come alive and was locked in a mortal struggle with the serpent. A portent, it seemed to the boy. A harbinger of things to come.

April Vázquez, a native of the North Carolina foothills, holds a B.A. in Literature and Language from the University of North Carolina at Asheville and an M.A. in the Teaching of English as a Second Language from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She currently lives in León, Guanajuato, Mexico, where she homeschools her daughters Daisy, Dani, and Dahlia. April’s work has been published or is forthcoming in Windhover, The Fieldstone Review, Eclectica, Foliate Oak, Ghost Town, New Plains Review, and others.

[…] http://journal.themissingslate.com/2016/07/01/father-chuy-sagrada-familia/view-all/ […]