A scholar criticizes Western society’s pressure on all Muslims to take collective responsibility for terror

By Sharmin Sadequee

Following every international or domestic terrorism act committed by a Muslim, the American-Muslim community divides under pressure on the issue of whether or not Muslims should take collective responsibility to communally condemn and apologize for the acts of a few individuals. On one hand is a group of Muslim activists and organizations who accept collective responsibility by condemning such acts. They are therefore viewed by the dominant Euro-American society as patriotic, “good†Muslims. On the other hand is a group of activists and organizations who reject collective responsibility and may be viewed as unpatriotic, “bad†terrorist sympathizers.

Critics of collective responsibility claim that it aligns one with the oppressors of Muslims, thus the supporters are viewed as “bad†Muslims. From their perspective, “good†Muslims don’t take collective responsibility but stand up against the state and its violence against Muslims in general.

As an American Muslim who has been working with and advocating for families of Muslims imprisoned preemptively in the United States, I have observed and experienced the impact of the divisions and debates around collective responsibility and collective condemnation for the last fifteen years and I want to disrupt it. This binary is imposed on Muslims by the state, but Muslim’s engagement with it is a result of internalized orientalist stereotypes, which paint Islam and Muslims as inherently violent and further perpetuate dehumanization and state violence.

To understand this process, one must ask: does criticizing responsibility and condemnation erase and hurt some community members and perpetuate state violence?  Does rejection of collective responsibility absolve Muslims from condemning certain harmful individuals? Does standing up against oppression itself become a form of oppression in the face of multiple oppressions? Is that too, a form of violence?

Lets examine collective responsibility. Collective responsibility is the idea that a group is liable for the wrongful acts of a few. It communicates the idea of a collective mind; all are connected to perpetrators without ever having contact with them. Historically, marginalized groups in the United States have been forced to be accountable for the actions of one person. This action is a part and process of racialization of marginalized communities of color and central to racism and Euro-American dominance in this country. Muslims subjected to such racializing politics have been forced to self-contaminate themselves with “guilt by association†with individuals who cause harm and share the same faith. But the limits of that responsibility must be interrogated.

Connected to holding Muslims collectively responsible for the wrongful act of a criminal individual is the state demand for collective condemnation. The Muslim community is under tremendous pressure from government officials, media platforms and the dominant Euro-American society to loudly declare and visibly perform its position against terrorism. The implication is that if Muslims don’t condemn, they secretly support terrorism and are therefore a potential threat, warranting suspicion, surveillance and retribution. In the absence of outward condemnation, all Muslims are guilty until proven innocent and the entire community should be punished and held responsible for any atrocity committed by the culprit. Although condemnation can operate independently, Muslims have been compelled to engage in collective condemnation of “terrorism†as a form of collective responsibility. A similar demand and response from Euro-American Christian populations in retrospect is missing when a white Christian engages in violence.

When officials in a liberal, secular, modern nation-state demand collective responsibility from Muslims, religion is mixed with the state in a ritualized way. The fusion of religion and state

formation was established in ancient times, when religion was the law that guided the conducts of people’s lives, and punished those who sinned against God or gods. Evolving from ancient state systems, modern nation-states such as the United States although claim to be secular, yet were bounded by religious symbols and ritual practices from their very inception. Politics and the legal and penal systems have always blended with Christianity. Among dominant groups, “sinners†have been replaced by criminals who are individually held responsible and punished in modern state systems.

Demands for collective responsibility and punishment are also not based on modern liberal principles. In a modern normative morality, only individuals are responsible for wrongful actions. When the dominant Euro-American society calls for collective responsibility, the Muslim community is compelled to engage in anti-American ethical conduct and forced to go against modern Western values. This position undermines the very concept and practice treasured in modern notions of accountability and justice. This stance also serves to legitimize the dominant discourse that Islam and Muslims are violent. Further, acknowledging association with wrongdoers also permits the US government to continue sending informants to mosques and Muslim communities. Supporting this position perpetuates unintended state surveillance, violations of civil liberties and human rights and increased civilian hate attacks on Muslims. Consequently, Muslims solicit more expansive counter-terror measures and affirm the use of governmental authority to cause harm to groups and individuals. In turn, they allow states to achieve certain implicit or explicit goals to maintain state power and control over the population—in other words, state violence.

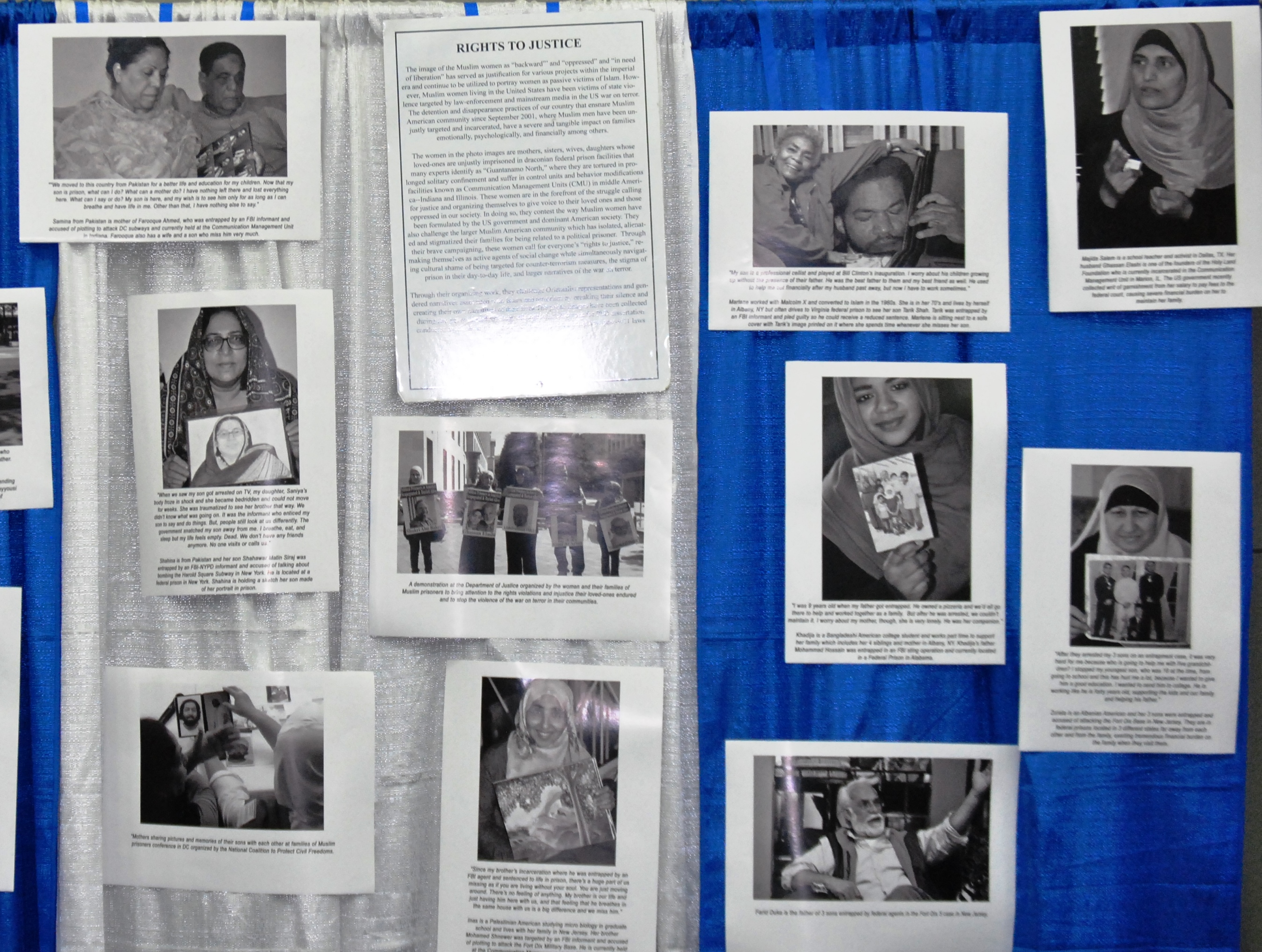

The expectation of collective responsibility is a state mechanism for continuously scapegoating innocent Muslims and Islam as “threats.†Scapegoats emerge during times of crisis and moral panic when individuals or groups resembling perpetrators get classified as a threat to societal values and wellbeing. An increased level of hostility towards the group collectively designated as the enemy is exhibited. Through these processes of scapegoating and panic, Muslims or people perceived to be Muslims are socially constructed as “terrorists.â€Â Scapegoating promotes social and political exclusion and othering of unwanted individuals or groups, empowering dominant groups to exercise power and discipline over both the scapegoated population and society in general. Muslims have been collectively scapegoated in the aftermath of 9/11;  innocent people have been detained, deported, arrested and tortured both domestically and globally in notorious camps such as Communications Management Units and Guantanamo Bay.  Muslim Americans have been subject to a separate system of justice where human rights violations through the judicial and penal system are accepted as legal and legitimate. When Muslims accept collective responsibility, they acknowledge the acceptance of abuse of Muslims as scapegoats for atrocities. Muslim Americans in particular, must rethink whether this position is helpful in the political struggle to secure collective dignity and self-determination.

Muslims critics of collective responsibility are usually also the ones denouncing collective condemnation in this debate. Public performances of rejecting collective responsibility and collective condemnation might be viewed by some as revolutionary, standing against oppressors and state violence. However, the outward dismissal of one’s responsibility and collective condemnation does not liberate Muslims from the implicit condemnation of individuals. Muslims’ abstention from condemnation vicariously affirms their support for condemnation by the state. Whether or not some Muslims reject responsibility and condemnation the perpetrator is subjected to the law and the state punishes the criminal. Rejecters of this position in effect support retributive justice, the idea that violence deserves to be repaid with violence. This is not a novel position for Americans, but retribution is a morally acceptable American value and daily law enforcement practice which garners strong public support for harsh criminal penalties.

Retributive violence is also connected to the way the state uses military force in global conflicts. Vicariously endorsing this norm tacitly supports the use of torture for terrorism suspects and the use of military force abroad. This stance supports the violent prison-military-industrial complex, which include the practices of government surveillance, use of informants and the predatory prosecution of Muslims. Critics of collective responsibility and collective condemnation inadvertently uphold the principles and practices of oppressive systems.

Furthermore, critics are much aligned with American and Western values and support modern, liberal, democratic normative principles of individual accountability when they indirectly condemn the culprit. The modern liberal morality assumes that there is individual autonomy in committing a crime and affirms the validity of criminal law. Therefore, this position does not absolve critics from condemning the wrongdoer; instead, it raises questions about whether or not and how this public performance leads to ending US imperial violence both domestically and globally. Not only do critics condemn few wrongdoers in this way, they actually also denounce another group of Muslims who have committed no act of violence— individuals the state selects as scapegoats for predatory prosecution.

The fissure between critics and supporters in the mainstream debates around collective responsibility and collective condemnation is based on the experiences of these two sides which homogenizes Muslim American experiences within this binary. Each position does not distinguish between criminal and non-criminal acts, that is, acts of atrocity and the criminalization of Muslims which involve no actions. When this position flourishes in public spaces, when an act of terrorism violence does occur, it encourages the Muslim mass to internalize the public debate and reject collective responsibility whenever one is accused of “terrorism,†even when there is no violence or intent of violence.

More than 500 innocent American Muslims have been targeted, imprisoned and condemned by the state in government-manufactured, “terrorismâ€-related cases through entrapment or violation of constitutional and human rights in the domestic “war on terror.† These Muslims are victims of predatory prosecution by the federal criminal justice system. These Muslims and their families have also been expunged and silenced by government institutions, dominant American society and the larger Muslim community.