‘Maligna, la verdad, qué noche tan grande, qué tierra tan sola!

He llegado otra vez a los dormitorios solitarios,

a almorzar en los restaurantes comida frÃa, y otra vez

tiro al suelo los pantalones y las camisasɉ۪

-Pablo Neruda, ‘Tango del viudo’

My first view of Asia was gold on black, Dubai International Airport almost lurid against the 3 o’clock darkness. When the desert sun rose, I retreated to the cool of the Food Courts, sitting on a concrete bench beside a koi pond and reading a few chapters of The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, clutching my Lemon & Ginger drink as though it might ward off the rising heat. Clumsy with tiredness after staying awake all the way from Heathrow, there seemed to be something irresistibly glamorous about the whole idea of sculpting a new existence abroad, something almost virtuous in having left family, friends and girlfriend behind to teach in an unknown country for no money at all. Suspended between two lives, who wouldn’t feel a flurry of excitement?

A couple of days later, I was stretched out on an unfamiliar bathroom floor, from time to time propping myself up just long enough to vomit into the toilet bowl. I went to bed that night next to a table littered with various pills, and woke up with a headache blinding enough to cover for all the hangovers I’d be missing out on in a country where alcohol is illegal unless you’re rich enough to circumvent the law. In full health, new experiences are almost always exhilarating, but in illness you long for the familiar — in my case, bland English food, comfortable temperatures, the faces of the people I love.

I’d left home trying to convince myself that I’d be ready to cope with my fair share of suffering. By most standards, I’d had an extraordinarily privileged childhood and — as arrogant as this sounds — never had to work particularly hard in school or at university. Settling down into a steady job with a steady wage would have felt like an abdication of responsibility; instead, I went to Bangladesh with the preposterous idea that I’d be leading an existence of quasi-mediaeval austerity, working from sunrise to sundown and living off bread and rice.

As if to highlight exactly how distasteful that vision of self-enforced ‘suffering’ is, a few lines from Pulp’s Common People suddenly come back to me:

When you’re laid (desperately want to write ‘lying’ here, so I will) in bed at night

Watching roaches climb the wall

If you called your dad he could stop it all…

Not quite true: if I called my dad, he’d be concerned but powerless to intervene, and the cockroaches tend to scuttle across the floor rather than climb the walls. Still, Jarvis Cocker has a point. The idea of wealthy Westerners feeling more virtuous because they’ve spent a few months in a less-fortunate country is troubling, to say the least.

In fact, some lives in Bangladesh are privileged beyond the dreams of wealthy families in the West. Having a maid and a driver is commonplace, even for middle-class families, and the country’s elite seem (although I have no first-hand experience) to live in palatial homes with dozens of guards, dozens of cars and a continual greed for more. The problem, as has been pointed out thousands of times before at much greater length than I can afford to go into here, is the gulf between the elite and the rest.

The rich regard the poor with a mixture of indifference and pure fear. Here’s a scene from the suburbs of Dhaka which might illustrate the point: I watch from a distance through the tinted window of my chauffeur-driven car as a beggar squirms on the dusty ground, pale soles upturned towards me. On either side of his spine, two twisted humps of muscle bulge upwards to form what looks like a shark’s dorsal fin. His limbs are so withered that walking is impossible. A young woman in a pink sari walks past and fumbles in her purse until she finds a small note (20 Taka, I think, although it’s hard to be sure from where I’m sitting) and presses it into the beggar’s clawed hand. A minute or so later, a man in a meticulously-ironed suit stops in almost exactly the same place, digs around in his pocket, pulls out a brand new iPhone and hurries on.

For me, the terrifying thing about that little anecdote is the ease with which I was able to turn away. When approached by people who must be going through a level of suffering beyond anything I could ever imagine, I’m able to coldly shrug and turn out my pockets and show them I don’t have the money. When they say ‘Please, boss’ (the standard way to address any white man here), I look impassive behind my sunglasses and am secretly relieved that I’m not carrying loose change. I’ve seen people actively pushing beggars away, or shouting ‘jao’ (go!), but somehow passivity is more shameful.

There are many ways in which I don’t quite fit in. I’d expected language to be the most significant barrier, but religion turned out to be of far more importance. Although Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, ‘the father of the nation’ and still the most visible face on Dhaka’s many political posters, initially intended Bangladesh to be a secular state, Islam is utterly dominant here, governing almost every aspect of life. In general, people are remarkably tolerant towards non-Muslims, as long as they identify themselves with another religion. In the first few days, I was asked hundreds of increasingly detailed questions about Christianity, and people seemed genuinely fascinated by my answers. What nobody seemed to consider was that I might not be a Christian at all. I imagine any suggestion of atheist sympathies would have been met with roughly the same mixture of ‘Is he serious?’ bafflement and outright disgust as the suggestion that I spent my Thursday evenings having vigorous sex with an assortment of farm animals.

Despite the obvious cultural differences, I surprised myself by very quickly beginning to feel at home in Dhaka, as though this city of two-hour traffic jams, stifling pollution and buses which would cause a national scandal if they were allowed to run on British roads, could somehow become ‘my’ city. I remember Seamus Heaney’s line about being ‘lost, unhappy and at home’, but that’s not quite it…

There have been moments, listening to Hindi songs in the car on the way back from a restaurant or spending time with the kids at my school or walking to the park in the evenings, when I’ve felt as happy as I’ve ever felt, and times when coming to Bangladesh has seemed like the best decision I’ve ever made. And yet it’s a country of contradictions — my Bradt guidebook says that ‘if Bangladesh were a person, she would be a youthful teenager’, and Dhaka certainly has enough wild mood swings to justify the description.

There have been moments, listening to Hindi songs in the car on the way back from a restaurant or spending time with the kids at my school or walking to the park in the evenings, when I’ve felt as happy as I’ve ever felt, and times when coming to Bangladesh has seemed like the best decision I’ve ever made. And yet it’s a country of contradictions — my Bradt guidebook says that ‘if Bangladesh were a person, she would be a youthful teenager’, and Dhaka certainly has enough wild mood swings to justify the description.

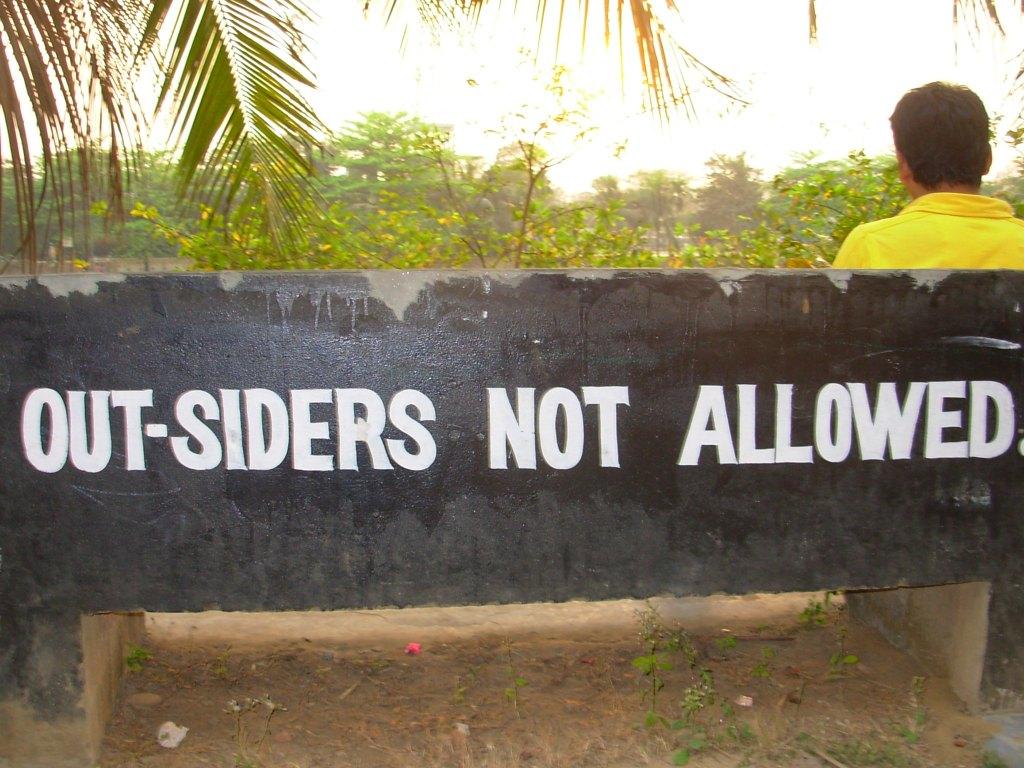

At the end of my first week, I went for a walk around ‘my’ area of the city, accompanied by one of the household staff (having been told it was too dangerous for me to go out alone). After a few minutes, we came to a small lake and sat down on a swing (ignoring the English phrase ‘no outsiders allowed’ and its Bangla equivalent) to watch the sun sinking behind a stunningly beautiful white mosque. The sun was so round and red it could have been cut from the Bangladeshi flag, and the lake looked postcard-calm save for one family pedalling a hired boat. On closer inspection, though, the water was discoloured and stagnant, and a dead carp floated pale belly-up just a few metres from my feet.

Sometimes Dhaka seems squalid, choked by the blue-grey haze of pollution, and sometimes it seems like a terrestrial paradise. Ultimately, perhaps, it is just another city that outgrows every description.

Jacob Silkstone is Poetry Editor at The Missing Slate and co-manages Alone in Babel, a blog on books and the publications industry. Formerly based in the UK, he is currently teaching at a primary school in Bangladesh.