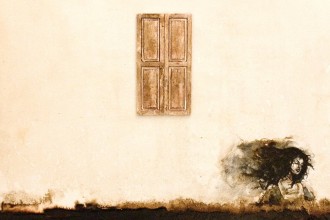

ID-04 by Fraz Mateen. Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery.

By Georges-Olivier Châteaureynaud

Translated from French by Edward Gauvin

Night falls. These pages will likely be my last. In a way, they will also be my first. And yet my books are everywhere. I owe them fame and fortune, but also the note of ambiguous despair on which my life now nears its end.

This much I have always known: to write is a disgrace. Don’t they know, who boast of it naively, that in every age it has mainly drawn the weak and mediocre, the spineless, eccentric, and effeminate, who found no other fitting activity? A man sound of mind and body does not write; he acts on, delights in, the real. Blessed are they who forget—screwdriver, bazooka, or slide rule in hand—the ulcerous idleness of the universe, which unveils itself upon the slightest inspection. When I was thirty, the air that seemed to intoxicate everyone else gave me no joy to breathe. I was waiting for that illness to declare itself, the illness that would save me: a book.

***

Wealth would come later, but already, back then, I did not want for money. My aunts, for love of the chubby, cheery baby I’d been, had appointed me their only heir. When they died, I was free of any attachments, personal or professional. There was nothing keeping me in Paris, nothing luring me anywhere else. Hawaii? Tahiti? The Seychelles? Acapulco? Or just plain old Nice? The world was my oyster, but I couldn’t care less. I ended up settling in Eparvay.

Eparvay, or France at its most down home and familiar. Which wasn’t unpleasant—just another kind of slumber. But I’ve given up trying to figure out just how it was, over a decade ago, that I picked out from a few hundred housing ads the one that led me there. After all, I spent whole nights considering it carefully at first. I even hired a private eye to look into the landlady. She turned out to be exactly as she seemed: a harmless old lady, all alone and going blind. Of course, I’ve even wondered about this suspicious, perhaps even symbolic, half-blindness… but what of it? The old lady who’d put up the ad was in fact a bit simple, and almost blind, like fate.

An appointment was made. I went to meet her. But how could I ever have done anything else? She welcomed me kindly, and after serving me a cup of tea, showed me around. Only later did I buy her out; that day, all we signed was a lease. That day, I became the tenant of that neglected little property, those walls thick with ivy, that fragile roof (which worried me no end), and along with the rest of the furniture, that armoire and its contents, of which I knew nothing. I was already less a tenant than a prisoner; I just didn’t know it yet. For the next ten years, tormented by such anxiety that I made every trip as short as I could, I was not to leave the house more than fifteen times.

***

The next morning, I set to work. All night, I’d sailed a dusky sea in dreams—my life, no doubt. In the lighted isle I was doing my best to reach despite tides that turned me endlessly aside, I saw, upon waking, the image of that peaceful home where I hoped at last to make my calling a reality. And so, at a very early hour, I set up my office in the very room where I now write these lines. It was furnished with a desk, shelves, and an armoire. Only the books have changed. Back then, the shelves sheltered only paperbacks and trade journals my predecessor had left behind. On the desk were a dried-out inkwell, scattered objects, a leather blotter. I took the cover off my typewriter and set it on a shelf, waiting, right by the pot of mint tea I’d brought up from the kitchen. Then I sat down and lined my pens up in front of me, my pencils, my erasers, my glue, my scissors, my staplers, my tchotchkes, and finally a cheap ream of paper for early drafts and another more expensive ream for later ones.

It was raining. I got up to open the window and stayed there a while, staring at the muddy puddles in the alley, the chestnut trees, the stone nymph that rose from a pool of such modest size that when she showed it to me, the old lady had called it a ha’penny pond. I realized I would not write. I shut the window and went back for a sip of tea. Standing in front of the desk, I untidied the objects I’d just arranged with such maniacal care. For years I’d been waiting for this moment, and now… nothing. The same old frustrated impotence, the same sourceless fatigue.

I was about to leave the room and take to bed, as I’d always done, when my gaze fell on the armoire. Just what was in there, anyway? Rags? Books? Family photos? Nothing at all? There was no key in the lock. I tried opening the door. It wouldn’t budge. I could’ve given up. What did I care? I could’ve left it all behind and grabbed the first train to Paris, and there—or anywhere else at all—kept on trying to write. Maybe I might even have managed. Maybe I passed my true fate by that day, another body of work that would have been mine alone?

Armed with a paper knife, seized with unaccountable fervor, I started prodding around in the lock. The rusted iron squeaked at the blade. Splinters of wood leapt from the side of the door at the pressure I exerted. Finally the bolt gave way, and the door opened, creaking. Two shelves were taken up with big black leatherbound tomes like accounting ledgers, flat on their dusty backs. I picked up the first to the left, on the top shelf. Instead of the columns of figures I was expecting, I read these words on the first page, in the green ink of a decorative hand:

Ananke

or

All Things to All People

A Novel