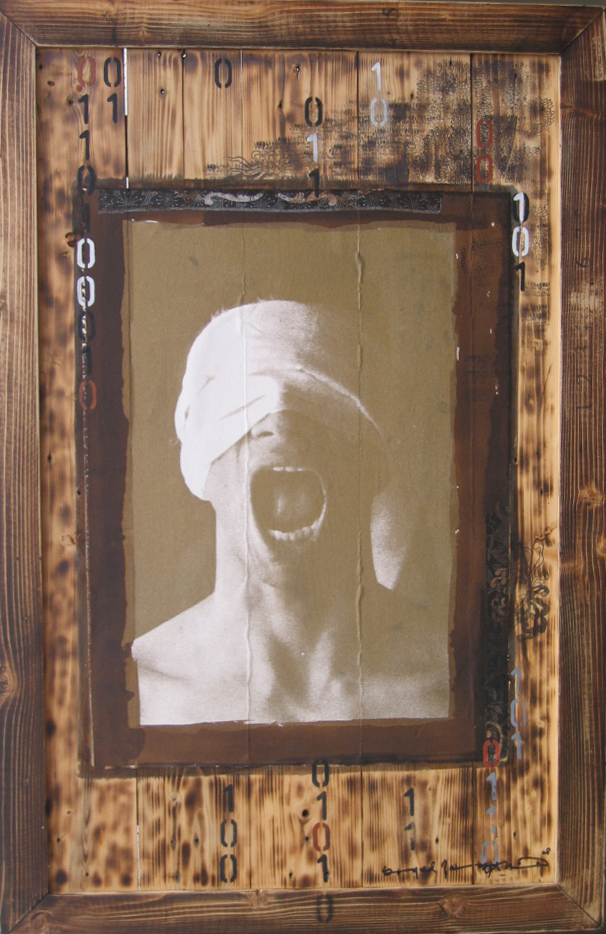

Image not found 3 by Syed Faraz Ali. Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery

By Kim Farleigh

He shuffled into the bare, cold room, his long, black coat reaching his ankles, ankles tied by chains, hands tied by ropes behind his back.

“You call this bravery?†he asked, his chin shooting up with the thrust of moral victory.

His faceless, balaclava executioners remained silent, the room’s windows boarded up shut. Rain thumped the boarded-up windows. High-pitched winds whined and thumped against the boarded-up windows, like incensed spirits trying to burst into the room, iron shutters shut firmly against the boarded-up windows.

“That wind,” he said, “is coming, and it’s going to get you all.”

Flashes of silver-grey sat in his black hair above his raised, black collars, his face glaring with pretentious amazement.

They pushed him up black, iron stairs, thrusting against his back, chains jingling against the black, iron stairs.

A black, iron balustrade reached a black, iron platform where he turned and said: “I’ve just stepped onto my launching pad into eternity.â€

A black, iron pulley sat above the black, iron platform. A noose, like a melted Dalà clock, teardrop hung on the platform’s black, iron balustrade, the rising cobra rope meeting the black, iron pulley above where the condemned scowled at the balaclava faces that surrounded him. The three large holes punctured into each of those balaclava faces, holes that permitted breathing and sight, made those faces resemble the demeanours of nightmarish beings. For decades, the condemned had managed through guile and savagery to delay the inevitable arrival of those nightmarish creatures; but the inevitable had arrived as it always does.

Low lights on the green-tinged, iron walls glowed dankly in the chilled room.

Under the black, iron pulley, the condemned man howled: “God protects his messengers.â€

He had executed thousands himself, often with his own hands, hypocrisy irrelevant. He was capable of saying anything, the past inconsequential in his fluid perception of what was necessary.

“Enjoy hell,†an executioner said.

“I’m leaving it,†the condemned replied; “the hell this country now is because of face-covering wimps like you.â€

His extended index finger on his right hand would have made a slow arc of accusation at the watching throng, had that finger been free.

“You’ll be paying for your cowardice,” the condemned pronounced; “and these winds, winds of howling revenge, are the prophecy of that inevitability. Don’t you little bunnies worry about that.”

His speech burst like torrents of certainty.

The teardrop noose continued drooping over the platform’s black, iron balustrade. Officials faced the drooping noose. The room’s low lights, lemon amid rust, glowed weakly above the officials, who were standing back to avoid cameras.

“Hiding from cameras,” the condemned predicted, as the noose got placed around his neck, “won’t save you when retribution’s winds begin wrecking your little worlds.”

A whining thump, like an exploding artillery round, cracked above the rumbling occurring outside.

The officials didn’t want to be seen on the internet backing this man’s execution; but his death had to be confirmed by influential figures to convince the majority that the tyrant had gone. Many people still wouldn’t mention the tyrant for fear he would return, as if he was the eternal embodiment of all that is evil in the human psyche, confirmation required from reliable witnesses that the tyrant had died.

“God,†that tyrant said, “takes back his messengers.â€

Prophecy protects its beholders from eternal annihilation. The officials admired this attempt to ward off non-existence, one wanting to applaud the condemned’s final thrust of Shakespearean assertion, this last possibility available for maintaining hope clutched, with proud vehemence, by he whose life had revolutionized amoral survival.

The coiled-knot noose covered a black, iron cone through which the rope slid to tighten the loop around the condemned man’s neck.

“God,†that man pronounced, “decides his messengers’ fates, not face-covering cowards afraid to be seen. Those without pride in their acts are dead.”

Changing circumstances had always changed his behaviour, his conduct having oscillated between authenticity and expediency, its instantaneous modifications never restricted by shame. He didn’t care who he was; he could be a merciless dictator, a prophet, a humanitarian, anything, re-inventions created to avoid eternal powerlessness, to extract the maximum from circumstances. Sincerity held no glamour for him, unless it was profitable.

“Enjoy hell,†someone screamed.

“I’m leaving it,†the condemned man proclaimed, “to fulfill my eternal destiny.â€

Most atheists when making such pronouncements smile, adding irony to proclamation; but not the condemned. He was so gripped by the need to produce his act of divine significance that he couldn’t diminish that performance’s authenticity, before his admiring audience of previous compatriots, through irony, continually playing on others’ fears and hopes, extracting all weapons from his vast cache of guiltless shamelessness.

He flashed downwards, his sudden iris emptiness leaving no hints of his fate; that unclassifiable, shrewd, ruthless enigma of expediency, who had ruled for so long through constant identity changes, not caring what his identity really was, had gone at last.

How many people face that like that?

He had consistently mocked his enemies’ limited perceptions of his capabilities, even having built monuments to his own genius just to annoy them; they had paid a high price for having initially assumed he was just a brutal thug. Their arrogance had come back to haunt them in the shape of a revenging demon with an extraordinary mind, their collective lack of perception having caused untold deaths.

That demon’s final comment, hissed out with whispering chilliness, like an unearthly spectre giving an oracle, a spectre with a dark gift for creating uneasiness, was: “My death will be avenged by the millions that you will have outraged by your cowardice. Where were you all hiding before the Americans came? In your little subterranean warrens, waiting like chickens in your hutches for Uncie Sammie. Shivering like the scared, little bunnies that you all are. Frightened, like now, to expose your twitching, rabbit faces. My followers will find one of you little rabbits and torture you to get the information necessary to get you all. And it won’t matter where you are in the world. Don’t have any doubts about that.”

Ocean silence boomed in the room as the condemned man swayed like a pendulum marking time, a short moment unnaturally long as everyone looked silently in different directions, while the shrieking, erupting artillery attacks built up outside.

Kim Farleigh has worked for aid agencies in three conflicts: Kosovo, Iraq and Palestine. He takes risks to get the experience required for writing. He likes fine wine, art, photography and bullfighting, which probably explains why this Australian from Perth lives in Madrid; although he wouldn’t say no to living in a French château. 116 of his stories have been accepted by 76 different magazines.