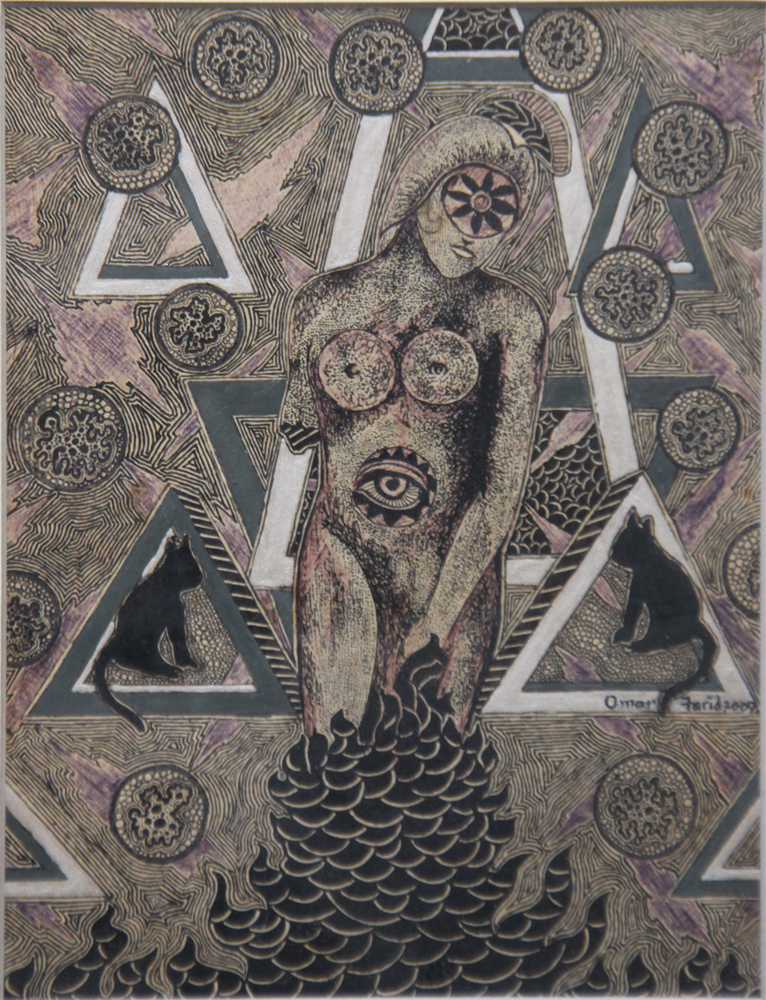

Axis by Omar Farid. Image Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery

By Mary de Sousa

Just before I let go, while she was still warm and heavy in my arms, I searched the hotel room. I wanted to give her something to keep; I wanted to mark her with me.

Instead I breathed into her ear all the things she might need. ‘If you fall, get up. If you fall again, get up again.’ ‘Always dry between your toes.’ ‘I love you, Plumpy Nut.’ Nonsense like that. I wanted to be the good fairy.

It had been another fearful day. I’d been shooting an A-Lister for a fundraising piece. She’d poked around the rubble, twitching her fine pashmina back onto her fine head each time I clicked, looking for victims to bestow herself upon, swooping on cripples.

She took off when she didn’t feel loved, when her yoga namaste met with shy, bemused smiles. ‘I can get Elton for the gala,’ she threw at me from the back of her jeep as it spattered my shoes.

I’d only done the job because I needed to be busy and to help Joe, which is funny when you think about it.

The baby was sitting alone. The weak sun pushing through the sagging tent had turned its skin a queasy blue. Its nose was slick with snot and it sat circled by glittering scraps of foil as if a strange ritual had taken place with it, a dejected Buddha, at the centre.

Plumpy Nut was written on the torn sachets. On the lips of the older children it became ‘plampynat’. When they were first brought into the feeding centre some fell asleep with the calorific goo still corking their mouths.

In Islamabad it had been almost fun. “The bed’s still shaking,’ Joe whispered as we finished and lay sweating that morning. At first we thought the trouble was inside, a wicked poltergeist throwing our photos from the walls and rattling the doors. When the servants downstairs wailed for Allah we scrambled into our clothes and out of the trembling house.

Joe left for the heart of it heading the white jeeps.

“The scale of it. It’s giving me a hard on,†he said.

I stayed behind a day to keep my appointment.

It was only when I got there, when I could see for myself what the fury had done, the roads melting down the hillsides, could smell the soft bodies under the rubble, that each aftershock turned my guts to liquid. It was bitter up there but every now and then I felt the sweat wrung out of me.

“Hello Plumpy Nut,†I said as I bent and picked up the child. It was a soft stinkball of ammonia and sweet oil, the eyes sadly comic with black kohl. I wrapped it in the long end of my shawl.

“Taking the little person to the big tent?â€

A sturdy young Viking dressed in baggy shalwar trousers and a Red Crescent jacket was holding the blue tent flaps apart, making him look like Superman.

‘I found her, I think it’s a her, on her own. I can’t find anyone she belongs to,†I said.

“They’re registering all single children there,’ he said pointing down the hill to where queues of people snaked away from a huge white tent. “There’s been some trouble with people just walking in and taking them.â€

‘It, she, needs feeding and her nappy changed,’ I said.

“They all do,’ he said sharply. ‘Who are you please?’

I flashed my volunteer badge and told him I had come up to take photos for my husband.

‘Sorry, I’m tired,’ he said. “I’ve met Joe. He’s already a hero. The hospital is like war, I mean back injuries like you never seen.â€

‘I’ll take her to the tent,’ I said.

My hotel was five minutes away. Iftar had just begun and I knew my driver Fahim would have gone to eat and enjoy his first smoke of the day. There were men everywhere telling people that disasters don’t just happen, especially during Ramzan.

“You people believe this is geology. They know it is God,†a doctor told me.

I pulled the shawl over the child’s head and walked quickly inside, past the skinny receptionist glued to a mute telly where a heavily made-up woman was emoting to the screen.

I locked my door. It was dusk and too dangerous to drive now. We would leave at dawn and be in Islamabad for lunch. I would tell Saima. I could trust her. She would help.

“Let’s get you sorted,†I said laying the child on the bed. I kept on like that, talking to her quietly in a voice that wasn’t my own, explaining, soothing us both.

Underneath the tight pullover was a grubby white vest. I peeled off the little shalwar trousers and a soaked strip of material that had been fashioned into a nappy. She kicked her legs and gurgled and looked at everything but me. I had the feeling she was keeping herself from my strangeness.

I filled the sink with hot water, praying the clunking pipes would stop, and worked some shampoo to a lather. As I lifted her there was a knock.

‘Yes?’ I said without opening the door.

‘Khana madam? Cold drink?â€

“Yes, chicken and rice and milk. Warm milk, jaldi please.â€

Holding her over the sink I cupped water over her legs. She shivered at the first warm splash but each one after drew a gummy grin. I dried her on my knee and the soft brown skin shone. With the kohl wiped off, her eyes were innocent. I wrapped her in a blanket and laid her down on the bed.

“Clean and dry in a trice,†I said as I washed her tiny clothes and spread them on the burning radiator.

The door knocked again and I moved her out of sight. The receptionist set the tray on the dresser and glanced at the drying clothes. I put some notes in his hand and he left.

I didn’t know if she would eat solids — she had banged her head against my breasts twice while I dried her — so I mashed up a tiny bit of chicken with the rice and blew it cool. I sat her on my knee.

Far from having to coax her, I had to work to keep up. No food aeroplanes for her. Her mouth was always open for the spoon and she ate noisily, her tongue pushing grains back out onto her chin. As she sucked at the cup of warm milk her eyes closed and I laid her down.

A burst of slap bass from my phone woke us both.

‘Everything is fine Madam?’ asked Fahim.

‘Yes, fine,’ I said.

‘I was worried when I didn’t see Madam at the centre,’ he said.

‘I won’t need you any more Fahim. Could you leave the car keys at reception.â€

“Madam, roads are very bad. Too much mud. I come to hotel,†he said.

“No. You can go back with Mr Joe,†I said.

“No Madam,’ he said, upset.

I lay beside her again. She grabbed my shirt with her hand and I kissed it.

‘Sleep,’ I said smoothing the fine black hair off her forehead.

Within seconds she was gone, little bubbles forming at her lips with each breath. I leaned in and smelt the sweet rose of the shampoo on her cheek.

When I woke the room was grey with dawn light and someone was whispering urgently close by.

“Please Madam.â€

I opened the door a crack keeping my foot against it.

“Men are here,†said the receptionist. “You come.â€

“Which men?†I said, my heart banging.

“You come,†he said.

Two bearded men were sitting perfectly still on the plastic sofa, one a taller, younger version of the other. Both were dressed in beige shalwar covered with long woollen shawls, the ends muddy. Their feet were bare in cheap plastic shoes. I pulled my dupatta over my breasts. When they saw me they stood quickly, staring at the child. The old man smiled and passed his hand over his eyes.

The receptionist spoke staring at the floor.

‘They want the baby child,†he said.

The young man stood and held my gaze while he spoke quickly to the receptionist.

The receptionist pointed at the older man. “He says this is dadi…grandfather. He is uncle.”

“How do I know?’ I asked.

The young man spoke harshly again and the receptionist looked at me with fear in his eyes.

‘Please madam. “He says ‘who are you.’ This is the baby family,’ he said.

“I was just feeding her,†I said.

“They have been looking for her all day,†said the receptionist. “They thought she was dead.â€

Now the older man stood slowly and asked something of the younger. The younger man raised his hand to stop him. I looked at the receptionist who cast a sad eye at the telly.

‘This man says you give the baby back now.â€

“I had no intention…†I said, my face flushing.

The older man spoke now.

“This man says he is sure you are a good lady,†said the receptionist.

And that’s when I searched the room, in those last minutes, as I dressed her in the stiff, warm clothes and wrapped her in the quilt. When I handed her to the old man he passed his cupped hand softly over her head and whispered something. She put her hand on his cheek.

I watched them from my window as long as I could and then lay down on the still warm bed.

I was tired. The night had been broken by the voices of people passing, sirens wailing, and she had woken. I had walked her around the room, bouncing her gently.

As we stood at the window she studied my face and the grizzling turned to yelps. I called her ‘bita’ (daughter) and sang the two words of a silly tune Joe sang sometimes, “meri jaan†(my darling) over and over again. She started to wail and wriggle. I sat and rocked her. She banged her head against my chest, her mouth searching.

“I’m sorry, baby,†I said.

When her lip pulled down and her eyes filled I opened my shirt and gave her my empty breast. She sucked noisily and was asleep in seconds. I lay awake uncomfortable with the feel of her mouth on my nipple.

The phone buzzed and I woke on the cold bed. I turned the volume down but it buzzed again.

“What’s going on Ana?†said Joe.

“Nothing,†I said.

“Fahim called. I don’t understand. He said you’re taking the car and something about a child?â€

He was talking to me as if I was standing on the edge of a high cliff.

“Honestly, I found this child and I fed her and cleaned her up a bit. That’s it.â€

“You took a child from the camp and brought it to your hotel? Are you fucking crazy!â€

‘Ana?†he said.

He sounded sad.

“Stop saying my name,†I said.

‘Were you wearing your name badge?†he asked.

‘I gave her back,’ I said.

He covered the mouthpiece and I could hear him shouting something about splints to someone.

“Do you need me to come?†he asked.

“If you’re asking the question…†I said.

“I can’t hear you Ana,†he said.

“There’s no point,†I shouted.

I had gone to the doctor with Saima. We had fought our way into the hospital through corridors lined with bloodstained trolleys. We were lucky. Dr Khan’s office was empty. ‘I am the only one with nothing to do,†he said smiling sadly.

He was the best. He had fixed Saima and all her friends, even the old ones. He would fix me too; I was young and healthy. “Just a little kick-start to the ovaries,†he had said handing over some tablets and in my mind I saw a large boot and some wilting sunflowers.

Today he had lost his earlier twinkle.

“There is no point to give you false hope,†he said.

“Are you still there?†Joe shouted.

A beating noise like a helicopter cut over his voice.

“I think I’m going to go home,†I said.

“Maybe that’s best,†he said without a pause.

There is a strange effect after an earthquake that you don’t often hear people talk about. It’s to do with the fact that one of the things that you held on to as true, that was so true that you never really questioned it, that the ground doesn’t move, is no longer true. You can no longer put your faith in it.

So that often in the days and weeks that followed when I was thousands of miles from the fault lines I would stop in the middle of an ordinary day and find myself utterly unable to decide if the earth was moving beneath my feet or not.

Mary de Sousa is an ex-journalist who has lived in Cyprus, Spain, Pakistan and Cuba. She has written a children’s novel, ‘The Halfie-Halfie Girl’, a magical detective novel set in India and Ireland. She is currently working on a novel, ‘Half an Hour from Pakistan’, about a British couple whose attempts to ‘do good’ end in disaster. She lives in Paris.