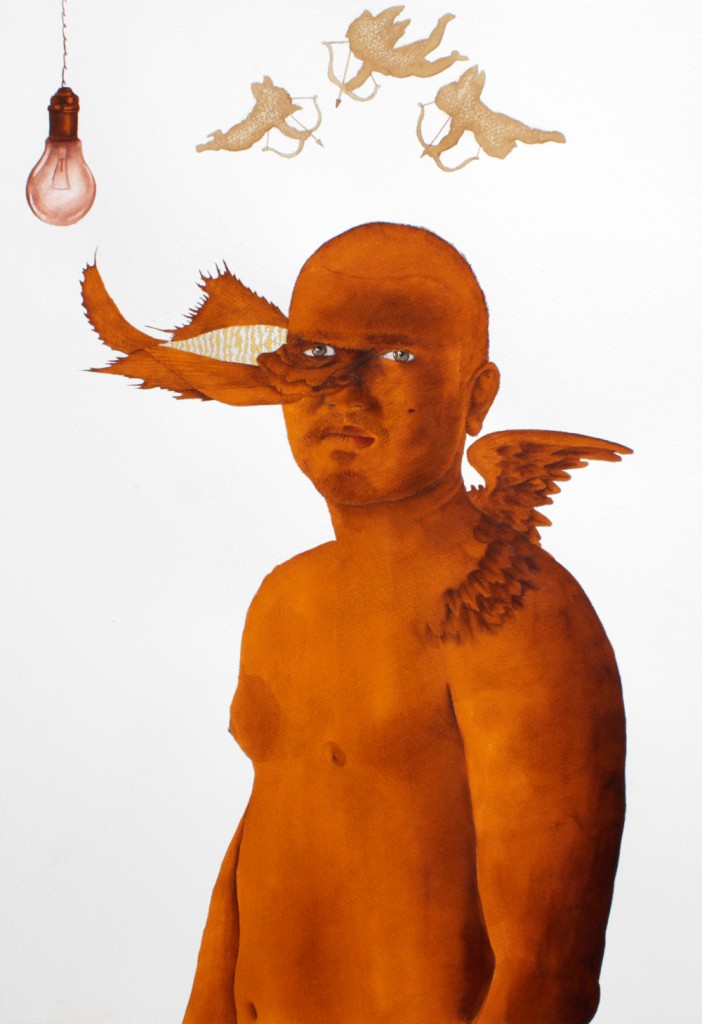

What Dreams may Come by Syed Faraz Ali. Image Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery

by Henriette Houth

Translated from Danish by Mark Mussari

He loved his children. Of course he did. That was why he kept them in his study in the basement. Where he sat writing his sermons and developing his theories about God and the nature of love, while the smoke from his cigarettes enveloped the room in an ever-thickening darkness.

They stood in a niche in the wall, along with a crucifix, a child’s drawing, and an octagonal shrine with small colored glass panes, exposed and protected all at once behind the thick glass covering the niche. There wasn’t anything indicating that the glass could be opened—or that it ever had been. No lock, no knob or handle, not so much as a frame or border. The glass just stopped where the wall began. For some reason that was what most bothered me.

He had shown me his study that first day when we walked around the house. He called it the house’s holiest of holies. Only joking, I think, and yet with something almost urgent in his voice. In any case, you could sense that it was a place just for him and no one else. It was the first time I really saw the room; in Pastor Kibæk’s time it had been an impassable jumble of more or less worn-out furniture, old playground toys, all kinds of hobby equipment, piles of books, and bags and boxes full of God knows what. A storage room, basically. Still, I had difficulty seeing what was so holy about it. In my eyes, it looked like any other basement room: low ceiling, dimly lit, with an almost imperceptibly dankness about it. What was holy must have been the work he did there. Or that little tableau in the wall niche. Or maybe both.

I couldn’t understand why he had chosen to have his office in the basement. There were lots of other rooms in the house. Rooms that were both larger and brighter, many of them even empty now. The house was enormous, much too big for just him and the children who were both there and not there. Who would know better than I after having cleaned there two times a week for almost five years now? There was a pause for a couple of years when the church council decided to use a home cleaning service instead. That was fine with me—I’ve never been at a loss for something to do. But when the subsidy for the home cleaning service got cut, the church council called and offered me my old job back. That was okay, too. Pastor Kibæk had moved in the interim—I think his wife had gotten a job in Aalborg—and a new pastor had moved in. But I definitely knew the house. Or should in any case, from any objective point of view.

The truth was that the house had never stopped perplexing me, a trait that became even more pronounced once the new pastor had moved in with his sparse furnishings. Instead of filling the house, they only seemed to expose it, highlighting its quirks, which the Kibæks’ cheerfully chaotic lifestyle had temporarily managed to camouflage.

It was a house conceived and built with height in mind. From outside there was nothing to indicate it was a rectory. It had to be its size. On the other hand, all the neighboring houses were around the same size, and you could really only see so much of the house behind the massive beech hedge shielding it from the road. The house was in an older residential neighborhood, at the end of a cul-de-sac, with a marsh in the back: a big, old monstrosity full of gratuitous corbels, bay windows, and corner towers rising up behind the hermetic hedging, making the whole thing look more like a bizarre geological formation than a rectory—which it wasn’t originally anyway. It was built around the turn of the last century by some long-forgotten local builder who had designed it as a private residence for himself.

That last part was something the pastor told me. Sune. That was his name. Sune Asger Nielsen. At least that’s what it said on his mail, which I periodically picked up off the doormat and laid for him on the kitchen table. We were not on a first-name basis; even in my thoughts he’s still nameless. And I’m certain I was never more to him than “the cleaning lady†or something like that. He also told me that the builder had allegedly built a secret room somewhere in the house. I don’t know where he heard that. I had never heard about it before.

He must have told me that one day when we were eating lunch, or more accurately, sitting at his kitchen table, me with my packed lunch, him with his cigarette and the cold cup of coffee he had brought up from the basement. It soon became a custom for him to come up and sit for a while as I ate my lunch. Or maybe you’d say: that was how it began. It seemed like he needed someone to talk to. Or talk at. At first, I didn’t say much; mostly I just listened. It was hard to make eye contact with him. The gaze behind his glasses would flutter and then vanish like a dying flame, or else it would hang there, almost in a trance, staring at the little icon hanging in the hall under the stairs. It was a picture of St. Christopher hanging above two portraits of the children, the same two portraits as those in the basement. He said he had hung it there to remind himself that he wasn’t an evil person.

He talked often about the children. He told me how they made bonfires in the garden in the summer, or lay in his bed, all three of them, while he made up stories for them or showed them the constellations. According to him, they were with him every other weekend. Sometimes they also came during the week, he said. They were free to come and go at his house whenever they liked. His ex-wife lived right nearby.

But mostly he talked about the things he hated and despised about modern times. He railed about the news coverage on TV; he cursed the church council, the Social Liberal Party, rampant individualism, the sexualizing of the public arena, and people’s expectations of the pastor as a person. He was furious about the dishwasher’s beeping and the vulgar clothes on the girls who were about to be confirmed. Yet all that was nothing compared to the anger he felt about adultery, not only what went on between people in real life, but as a theme presented in books, newspapers, and TV. And then there were “the rich and famous,†who were also disgusting—their comings and goings, the media exposure, their very existence. It never became totally clear to me just who or exactly what he meant, but “the rich and famous†not only made regular appearances at his services, he pointed out, but were also frequently spit out right there in the kitchen, among everything else he was so angry about. The “fluttering.†It was an expression he used often. He met it everywhere, this flutter. Fluttering had become the modern person’s most significant character trait.