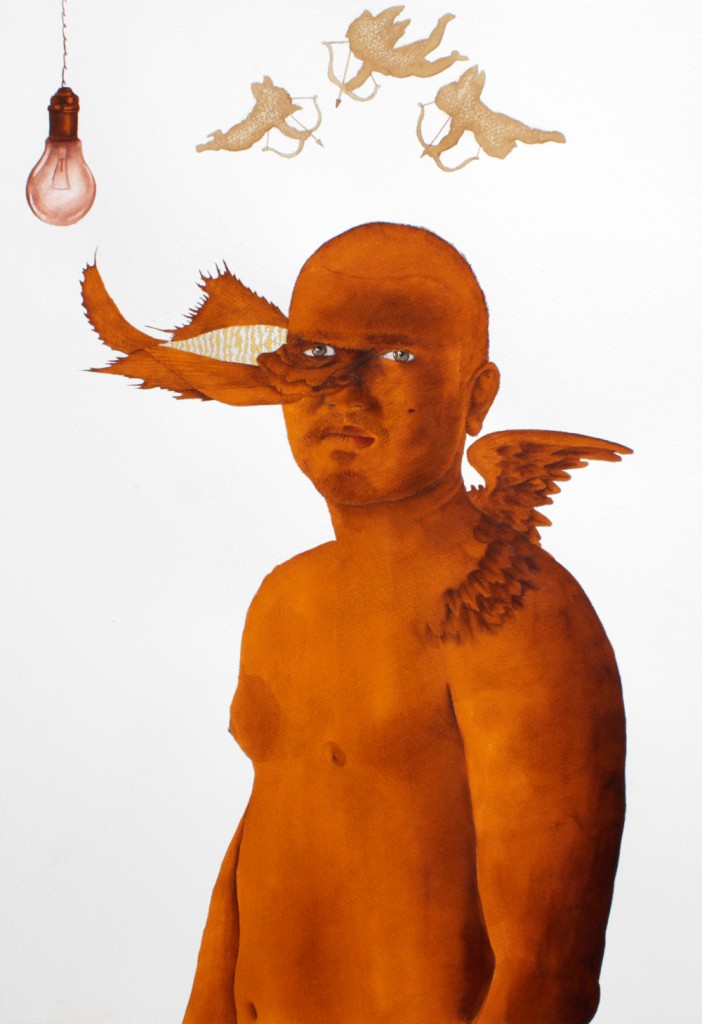

What Dreams may Come by Syed Faraz Ali. Image Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery

by Henriette Houth

Translated from Danish by Mark Mussari

He loved his children. Of course he did. That was why he kept them in his study in the basement. Where he sat writing his sermons and developing his theories about God and the nature of love, while the smoke from his cigarettes enveloped the room in an ever-thickening darkness.

They stood in a niche in the wall, along with a crucifix, a child’s drawing, and an octagonal shrine with small colored glass panes, exposed and protected all at once behind the thick glass covering the niche. There wasn’t anything indicating that the glass could be opened—or that it ever had been. No lock, no knob or handle, not so much as a frame or border. The glass just stopped where the wall began. For some reason that was what most bothered me.

He had shown me his study that first day when we walked around the house. He called it the house’s holiest of holies. Only joking, I think, and yet with something almost urgent in his voice. In any case, you could sense that it was a place just for him and no one else. It was the first time I really saw the room; in Pastor Kibæk’s time it had been an impassable jumble of more or less worn-out furniture, old playground toys, all kinds of hobby equipment, piles of books, and bags and boxes full of God knows what. A storage room, basically. Still, I had difficulty seeing what was so holy about it. In my eyes, it looked like any other basement room: low ceiling, dimly lit, with an almost imperceptibly dankness about it. What was holy must have been the work he did there. Or that little tableau in the wall niche. Or maybe both.

I couldn’t understand why he had chosen to have his office in the basement. There were lots of other rooms in the house. Rooms that were both larger and brighter, many of them even empty now. The house was enormous, much too big for just him and the children who were both there and not there. Who would know better than I after having cleaned there two times a week for almost five years now? There was a pause for a couple of years when the church council decided to use a home cleaning service instead. That was fine with me—I’ve never been at a loss for something to do. But when the subsidy for the home cleaning service got cut, the church council called and offered me my old job back. That was okay, too. Pastor Kibæk had moved in the interim—I think his wife had gotten a job in Aalborg—and a new pastor had moved in. But I definitely knew the house. Or should in any case, from any objective point of view.

The truth was that the house had never stopped perplexing me, a trait that became even more pronounced once the new pastor had moved in with his sparse furnishings. Instead of filling the house, they only seemed to expose it, highlighting its quirks, which the Kibæks’ cheerfully chaotic lifestyle had temporarily managed to camouflage.

It was a house conceived and built with height in mind. From outside there was nothing to indicate it was a rectory. It had to be its size. On the other hand, all the neighboring houses were around the same size, and you could really only see so much of the house behind the massive beech hedge shielding it from the road. The house was in an older residential neighborhood, at the end of a cul-de-sac, with a marsh in the back: a big, old monstrosity full of gratuitous corbels, bay windows, and corner towers rising up behind the hermetic hedging, making the whole thing look more like a bizarre geological formation than a rectory—which it wasn’t originally anyway. It was built around the turn of the last century by some long-forgotten local builder who had designed it as a private residence for himself.

That last part was something the pastor told me. Sune. That was his name. Sune Asger Nielsen. At least that’s what it said on his mail, which I periodically picked up off the doormat and laid for him on the kitchen table. We were not on a first-name basis; even in my thoughts he’s still nameless. And I’m certain I was never more to him than “the cleaning lady†or something like that. He also told me that the builder had allegedly built a secret room somewhere in the house. I don’t know where he heard that. I had never heard about it before.

He must have told me that one day when we were eating lunch, or more accurately, sitting at his kitchen table, me with my packed lunch, him with his cigarette and the cold cup of coffee he had brought up from the basement. It soon became a custom for him to come up and sit for a while as I ate my lunch. Or maybe you’d say: that was how it began. It seemed like he needed someone to talk to. Or talk at. At first, I didn’t say much; mostly I just listened. It was hard to make eye contact with him. The gaze behind his glasses would flutter and then vanish like a dying flame, or else it would hang there, almost in a trance, staring at the little icon hanging in the hall under the stairs. It was a picture of St. Christopher hanging above two portraits of the children, the same two portraits as those in the basement. He said he had hung it there to remind himself that he wasn’t an evil person.

He talked often about the children. He told me how they made bonfires in the garden in the summer, or lay in his bed, all three of them, while he made up stories for them or showed them the constellations. According to him, they were with him every other weekend. Sometimes they also came during the week, he said. They were free to come and go at his house whenever they liked. His ex-wife lived right nearby.

But mostly he talked about the things he hated and despised about modern times. He railed about the news coverage on TV; he cursed the church council, the Social Liberal Party, rampant individualism, the sexualizing of the public arena, and people’s expectations of the pastor as a person. He was furious about the dishwasher’s beeping and the vulgar clothes on the girls who were about to be confirmed. Yet all that was nothing compared to the anger he felt about adultery, not only what went on between people in real life, but as a theme presented in books, newspapers, and TV. And then there were “the rich and famous,†who were also disgusting—their comings and goings, the media exposure, their very existence. It never became totally clear to me just who or exactly what he meant, but “the rich and famous†not only made regular appearances at his services, he pointed out, but were also frequently spit out right there in the kitchen, among everything else he was so angry about. The “fluttering.†It was an expression he used often. He met it everywhere, this flutter. Fluttering had become the modern person’s most significant character trait.

I didn’t really disagree with many of his opinions, in and of themselves. It was more the disproportionate anger that accompanied them, an anger that seemed all too big and amorphous to contain all the things he railed against, an anger that seemed more constitutional.

He also became angry at me once. It was later on, when I had begun to say more, maybe even one of the first times we had something that seemed like a conversation. Anyway, that’s how I saw our exchange of words. We were talking about love, I remember. Love in the Christian sense, charity. I was the one who called it charity. “Charity!†he sneered, as if it was the epitome of all of modern culture’s inanity. It seemed almost as if he had been waiting for that cue just so he could throw himself into what was really on his mind: the rampant individualism, the psychologizing of human existence, the whole culture of self-improvement and its facile spirituality, all just a thin shroud over modern man’s superficiality and inability to take an interest in anyone other than himself.

I said something along the lines of—which was true—that for the most part I agreed with what he was saying. Still, it wasn’t totally wrong, as a psychologist would see it, that a person incapable of loving or at least respecting themselves is not in any position to love others, and that self-improvement or some form of therapy could therefore—

I never managed to finish my thought. Suddenly he banged his fist on the table and shot up so fast that the chair fell over.

“I don’t want to hear this,†he hissed. “This isn’t a fucking conversation—it’s just an exchange of attitudes!â€

I have to confess that I was rather dumbfounded. It was totally unexpected. He stood there in the middle of the room, his mouth hardened into a strict line; and then he turned round, standing at the kitchen table, his back towards me. He stood that way for a while, with hands clenched against the tabletop and his shoulders arched. Eventually he let his hands fall and said, without turning around:

“Forget it. Have a cup of coffee, if you’d like. I’m going down to work.â€

And he left.

Normally, he directed his anger more at impersonal things: social, political, or cultural matters. It probably comes as no surprise that I was a little fascinated—if not actually impressed—by the energy in this constant store of anger. Its ability to surface almost out of nowhere with a power and intensity that made any question of rationality fade. An anger that barely seemed containable in that small kitchen with its cozy paneled cabinets.

At other times, he could be sullen and silent, barely answering in monosyllables, as if he were gathering his strength for later eruptions.

I wasn’t really sure I believed all that about the secret room. Or even if he did, for that matter. He said so many strange things. In any case, I couldn’t see the point of wasting square meters—which even then, over a hundred years ago, must have been quite expensive—on a room nobody would ever use. The whole idea seemed foolish, like some gothic fantasy or something out of a child’s fairy tale. Still, the secret room kept popping up in my thoughts, and sometimes, just for fun, I tried to figure out where it was. It was almost impossible not to think about it when I was moving around the silent house, the vacuum cleaner’s head gliding like a probe along the tall paneling. From the very moment the possible existence of a secret room was mentioned, the idea of it became just as much an inseparable part of the house as the room itself, whether it actually existed or not. And maybe it wasn’t totally out of the realm of possibility. There was something about the house, something eccentric or irrational, that made the possibility of such a whim seem if not obvious then at least plausible.

It was a three-story house, four with the cellar. The stairs between each floor sat just about in the middle of the house, like a not particularly straight vertical axis around which the rooms dispersed in an apparently improvised sequence—as if they followed some incoherent line of thinking full of sudden impulses and accidental flourishes rather than any coherent master plan.

The way into the house seemed like a rite of passage in several stages. The first barrier was the hedge with the red-painted wooden gate. The hedge, which I guess was taken care of by the cemetery’s gardener, was so massive and wrapped so tightly around the gate that it looked as if the gate had been mounted directly into it. Inside was a short flagstone path leading up to the main steps. From the front door, with its gold bottle-glass panes, you entered a porch that could just as easily have served as the entrée hall all by itself. From here you entered yet an even larger foyer with a strangely misplaced cross-vaulted ceiling, and finally into yet another hallway from where the steps snaked in a lazy curve up toward the other floors, while a hidden flight of stairs beneath them led down to the basement. Once this far in, there was no sign of the outside world, its cars, sidewalks, and traffic lights were far away. You were surrounded by doors and openings, and walls that cracked and ran around corners, leading one ever further in.

It was a house with an unusual number of doors, at least two in every room, and three or four in many places. The sheer number of doors meant that the rooms were connected crosswise, and I think that contributed to making it so hard to cope with the house. It was as though the idea got jumbled up among all these entranceways and exits, and ended up leading aimlessly around, with nothing to stop it than the outer walls, which in and of themselves rarely demarcated any clear or definite boundary, but faded off instead beneath the eaves or bulged out in bay windows or corner towers.

The only exception was the bedroom on the first floor. There was actually only one door here. Obviously, it had always been that way, but it was only later that I had any reason to notice it. At first, I was more consumed by the basement office, where I officially had nothing to do. He never mentioned whether or not he took care of the cleaning there, but I had probably assumed so. Or maybe it was just never cleaned. In any case, from the very start it was clear that my range of action did not include the basement. Unofficially, on those rare occasions when he wasn’t home, I went down there anyway.

In contrast to the hushed, almost uninhabited atmosphere hanging over the rest of the house—the sense of something provisional, rooms still waiting to be taken into possession—the basement office seemed inhabited in a completely different way. Obviously, this was where he spent the largest and most important part of his time. The desk had been overrun. Stacks of books were piled up with a forest of small yellow post-its stuck between their pages, or they lay open on top of each other among half-filled-out birth certificates, pieces of paper with notes, bank letters, ashtrays, half-filled coffee cups with small islands of mold in them. Capsized rows of books, binders, and journals filled the bookcases along two of the walls. An old rocking chair sat in the innermost, darkest corner. And then that silent stare from the wall niche. There was something at once repulsive and puzzling about that small tableau that drew me with a force I cannot explain. It was as if it sucked all the energy in the room to itself. I often found myself standing there mesmerized in front of it while I felt the children’s eyes fixed upon me. I couldn’t look at them for very long; instead, I tried to look into the shrine through the small colored windows.

Children at that age grow quickly. But not that quickly. And they don’t grow younger. The girl I had seen in the garden one day—the only child I’d ever seen in or around the house—was at least three or four years younger that the girl in the picture. The boy next to her I had only seen here. His face was childish but his eyes were dark like the wells in a Russian fairy tale, like holes burnt into the photograph. You could just make out something glinting between his slightly separated lips. Maybe he was wearing braces.

Sometimes, especially in winter when the sun was low, a sunbeam would break through the dry vine leaves that almost smothered the windows and strike the shrine, which reflected the light even farther and bathing the little scene in an almost apocalyptic glow. For a brief moment, the children seemed to almost flare up, standing there glowing in the light from the shrine’s colored glass. I didn’t know why, but sometimes I imagined that it was in these moments that he most loved them. And it really was just moments. Before long, the sunbeam would move on, leaving the room to sink back into a formless twilight.

But both light and darkness exist. Who would know that better than he would? After all, that was his profession. Darkness needs a place to exist and walls to contain it, or else it will spread. He had chosen the garage initially because he didn’t have a car. But whether the darkness had grown too large, or the amount of empty bottles had left even less room for it, the garage eventually became too small for it. The darkness had escaped from him. It had infiltrated the pine trees at the end of the garden, its fingers mingling with the vine leaves, seeping in through cracks and crevices in the masonry. It gathered behind his back on late winter afternoons when he sat in his office working, slumped over the desk, as if he were carrying the weight of the whole house on his shoulders. This is how I picture him, surrounded by the monstrance of the desk lamp, a lonely back that seemed to suck all the darkness to it.

It wasn’t because I had missed other opportunities in life, or because I had any special affection for cleaning houses. Nor did I hate it. That wasn’t the reason I began to clean other people’s homes. Actually, it wasn’t the cleaning I was interested in when I was vacuuming or swinging around some rag. What most fascinated me were the people whose private spheres I was moving around in. As far back as I can remember I’ve loved to look at houses, to imagine the lives behind the walls and the people who live there. I’ve lost count of the train, car, and bus trips I’ve spent musing over a glimpse of an overgrown garden, the crooked hanging blinds in a first floor apartment, a U-shaped farm among the whispering lindens, patrician villas, modernist complexes, row houses with raised beds and paved driveways, the warm yellow light from an attic window, a man in a kitchen with a fork lifted to his mouth. All these signs and clues; fragments of stories, destinies, lives.

Cleaning other people’s houses was a legitimate way to get into some of the homes I would have no access to otherwise. Just as it requires certain tools to clean—vacuums, buckets, cloths, and such—my body’s ability to handle these tools and the work that could be performed with their help was merely another tool for pursuing what really interested me: gaining insight into other people’s lives. It was kind of like anthropological fieldwork, driven by an obvious yet at the same time half-covert fascination people have always had for studying their fellow species. Also, if the truth be told, it was a lot more enticing than the master’s thesis in anthropology I was supposed to be working on for the past six years. And I got money for doing this, too.

Still, I’d never imagined I was ready to go so far to appease my curiosity. Actually, I hadn’t imagined anything. At least, I’d never thought of him in that way.

It was autumn, late in November, I believe. A quiet, foggy day. I was in the middle of cleaning the bedroom on the first floor. The fog was so dense that it seemed to be pressing against the windows. As if it were too big for outside and wanted in. The three pine trees at the end of the garden were barely discernible, three woolen shadows. I had just finished washing the floor and was about to lay the kilim rug in front of the closet when I heard a sound behind me. I turned my head to see the pastor, standing in the doorway. He had one arm resting on the doorframe and was staring at me. Well, with his face turned toward me—the gaze behind his glasses was more difficult to grasp. He didn’t say anything; he just stood there. I let the rag splash into the bucket and shoved the rug in place with my foot. Why was he standing there like that without saying anything? Why wasn’t he sitting down in his office like he usually was? I grabbed the handle on the bucket and started walking toward the door. His expression said nothing about moving. I continued until I was standing right in front of him—I stood there with the mop in one hand and the bucket in the other. Surely he could see I was on my way out? But he still wasn’t moving; he just stood there in the doorframe and stared at me.

At that moment it occurred to me that there were no other exits. No need to look. There was only one door in the bedroom; there had never been more. I tried to hold his gaze, to look him right in the eyes. But even that close, despite the fact that his gaze was ostensibly directed at me, there seemed to be no eye contact. As if his eyes were shrouded by a membrane, an extra layer of glass behind his glasses. I don’t know how long we stood like that. Certainly not long, or I wouldn’t have still been standing there, with my bucket in one hand and the mop in the other, when he reached out and closed his hand around one of my breasts.

I still don’t know why I didn’t pull away, why I didn’t resist, toss the bucket’s contents on his head, something. Just a step or two backwards, it would have been easy, because it all seemed to be happening in slow motion—at least that’s how I remember it. I guess I never thought of it. It was like a gap in time. An empty, white hole in reality that spread with lightning speed, threatening to swallow us up. Anything resembling free will or intent had abandoned me. My body had become an impersonal object waiting, with cool, almost detached interest, to see what his next move would be.

That’s pretty obvious, you might say. We were standing right in front of the bed, me with my back to it, him in front of me, both bigger and stronger than I.

I remember that at some point while he was pressing me up against the headboard, I was thinking about that blue elephant in the children’s room on the other side of the wall. I was standing there with it in my hand less than an hour earlier. Its eyes, made of some kind of plastic, had felt quite cold against my fingers. I don’t know why that had surprised me —it was cold in that room too, and it was on the bed right beneath the old single-pane window—it had almost made me pull my hand away, as if I had burned it.

On the other hand, it didn’t really surprise me that anger was his actual motivation here, also. What did surprise me was the ease with which I surrendered to it, made it my own. I discovered that I enjoyed frustrating him, inflating his anger just to get the chance to puncture it, to see it fall pitifully to the ground. What did he have to be so angry about? He had this way of pulling his lips back and baring his teeth that I had never seen on anyone else. Like some predator that has just dug its claws into its prey to tear it apart. It would have been almost funny if it hadn’t seemed so desperate.

It went on for the next few weeks. Or months—it’s hard to say exactly. I don’t really remember one time from the next or how often it happened. Only the first and last times stand out. We were more combatants than lovers. Basically, he had handed me the ammunition. What was my ruthless gentleness other than his own church’s requirement to turn the other cheek?

The final time was different. I knew it as soon as I heard him on the stairs. I hadn’t seen him at all that day. It sounded like a herd of cattle was barreling up the steps. At times I could hear him huffing and muttering. Then there was a distinct bang followed by a thump, as if he had slammed into the wall and fallen. For a moment there was total silence. I was about to go out and see what had happened. And then I heard him huffing and rumbling about again. Shortly after he stood there, stinking drunk, leaning up against the doorframe in a way that was supposed to appear nonchalant. A sour stench of booze and cigarettes wafted from him. His hair was hanging in greasy wisps on his forehead.

“Sooo … you’re fuckin’ standin’ there again, huh…,†he slurred. He scowled over the rim of his glasses while he struggled to gain control of his knees, which were bowing and flexing, threatening to give way beneath him.

It didn’t take much to knock him down onto the bed—he almost fell over on his own. He made some half-hearted attempt to pull me with him, but he soon gave up. He let himself fall back and just lay there. His muttering was soon replaced by a light snoring. He was lying flat on his back with his legs hanging over the edge of the bed. I stood for a moment watching him. On the front of his pants, from the fly down along one thigh, was a large stain. He lay with his arms at his side, slightly bent at the elbow, his palms facing upwards. It almost looked as if he was in the process of giving me benediction.

I backed cautiously toward the door. Just as I was on my way out, I felt something tugging at my arm. It gave me a start before I realized that it was just my sleeve, which had gotten caught in something. A key. The loose knit fabric had caught on a key sitting on the inside of the door. On an impulse, I took it with me and locked the door from the outside. Then I left the key in the keyhole.

I still have that blue elephant somewhere. I kind of regret taking it. I don’t know why I did it—it was foolish and irrational. Maybe I wanted to see if anyone would miss it. Some sort of proof that the children even existed. How I imagined I would get this proof I have no idea. Surely I must have known, as soon as I took it, that I would never come back. And of course the children existed. Why wouldn’t they?

Henriette Houth was born in 1967. Her publications include two collections of poems, two books of architecture and design, two collections of short stories and a children’s book. ‘Greatest of These’ is from her recent collection of short stories, ‘Mit navn er Legion’ (My Name is Legion). Currently Ms. Houth is working on a novel.

Mark Mussari has his Ph.D. in Scandinavian Languages & Literature from the University of Washington in Seattle and has done translation work for numerous Danish publishers. He recently translated Dan Turèll’s Murder in the Dark for Norvik Press, as well as Morten Brask’s The Perfect Life of William Sidis. A scholar of Danish literature, art, and design, Mussari has also translated books on Finn Juhl and Hans J. Wegner for Hatje Cantz. He has written a number of educational books including books on Shakespeare’s sonnets, popular American music, Haruki Murakami, and Amy Tan. He is currently writing a book on Danish design for Bloomsbury Press.