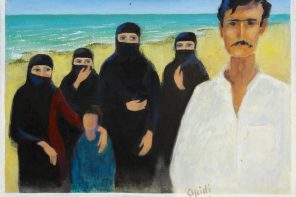

Aik Fauji by Mohammad Ismaeel. Courtesy: ArtChowk Gallery.

Teaching children how to perpetuate violence

By Nancy Caronia

Kidnap is the name of the game. My nine-year-old niece, her two friends—Fred and Kristin—are moving at breakneck speed from one end of the basement to the other. I have only recently arrived to my niece’s birthday party. She has asked me to join them, but I’m being excluded. Fred, tall for nine with short brown hair, and Kristen, thin with blond hair to her waist, are the kidnappers and my niece, the shortest of the three with dark brown shoulder length hair is the kidnapped. The kidnappers take jump rope and tie my niece’s hands and feet. They grab plastic bats and other toys to use as instruments of torture. The abducted cannot scream, although my niece yells: “Stop! Stop! Stop it!â€

Kristin flips her hair and emits a whistle: “We’re trying to help you. To show you what to do if someone takes you.â€

I am still. I do not have children and have not seen this game in action before. My niece knows this information. My niece, who refuses to remain quiet, is untied.

Her cheeks puffed up and red, she stands next to me. “Do you want me to go upstairs?†I ask.

“No,†she is definitive. I am to be a witness. The game continues. After an extended discussion, Kristin and Fred tie my niece up again. My niece fights back—again. She yells, against all the rules, whatever those rules might be. They climb on the white leather loveseat where I am pretending to pay less attention to their game and more to the episode of Everybody Loves Raymond flashing on the widescreen television across the room.

“Why do you play this game?†I ask, trying to sound innocent.

“But why, I ask? It’s so mean. And kind of violent.†I try to be casual. I don’t want to accuse, but there it is in my voice. In my choice of the word: violent. They are nine. I try to remember that they are nine, but I am dumbfounded by the violence with which they seem so comfortable.

“Well, you played this when you were our age. You had this game,†Kristin accuses me of forgetfulness.

“No,†I reply. “I didn’t. I didn’t play like this.â€

They continue moving like feral beasts, but they have grown quiet in their thoughts. I hear the missed beat of a chance to overtake my niece.

My sister, my niece’s mother, comes downstairs. She is the older version of what my niece will someday look like. I say, “I’m staying. I’ve been told to stay. But even if I weren’t, I’d stay.â€

“Good,†she says. She knows she cannot control everything. She knows better than I do how fast they grow up. She knows this game too well.

“Do they play like this all the time?â€

She sighs and says nothing. She leaves after a few moments, enough time for the girls to tie up Fred.

I wait until they are crawling over me on the loveseat before I say, “Well, I didn’t play like this when I was your age.†It gives them pause, although you could be forgiven for missing the slow down in nine-year-old bodies. I continue to watch/not watch Everybody Loves Raymond. They continue to move, but I have removed the heart from their game.

My mind wanders. I wonder if I have lied to them. I grew up with Cowboys and Indians. War. Ringolevio. But when I was my niece’s age—the decade of the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, the Mets first World Series, the Jets first Super Bowl, we had no clear victor. We liked to be Indians as much as we did cowboys—maybe more. The tide was turning. Or so we were told. Or so we wanted to believe. Perhaps this is my version of denial, or perhaps I am just a white ethnic confused by assimilation tales of success. Maybe I have now transformed my parents’ version of the “good old days†into mine. Enemies, after all, are different than victims, no?

Then I remember the boy who lived across the street when I was my niece’s age. He was, as the term was used then, mentally retarded. He and his family were ostracized. No one was allowed to communicate with him. No one ever talked to his family. I do not remember what he looks like any longer, what his name was, if he had brothers or sisters. I do not remember the family surname. I am uncomfortable remembering this boy who I do not remember. I know this ostracism was the way of assigning blame to what or who was not perfect, to what or who did not fit in with the working class ethnic neighborhood’s image. To who or what compromised visions of successful assimilation. I see a blurry frame moving across the street, my friends running to the top of the their stoops as he passes by, taunting him with slurs until he passes. His voice emits a guttural whimper. I stand silently watching, waiting for something to happen. It never does.

I cannot help but think that we are teaching children how to perpetrate violence, how to dehumanize one another with no chance for redemption or change. We are also teaching them how to be victims. There is no grey area in this construction just as there was no grey area for me and my friends with that boy I cannot name except as a label that was not a description of some part of his essence—we turned him into a perpetrator even as he was the victim.

It takes only ten minutes after I tell my niece and her friends that I’ve never played Kidnap before they abandon the game. My niece sprawls across my lap. The other two huddle nearby. Taking shelter. Until they run off. Again.

Nancy Caronia is a Pushcart Prize-nominated author whose most recent work has appeared in Animal Literature Magazine, New Delta Review, and Lowestoft Chronicle. She is a Lecturer with the University of Rhode Island Honor Program where she teaches contemporary literature and composition. She and Edvige Giunta have a co-edited the collection: Personal Effects: Essays on Culture, Teaching, and Memoir in the Work of Louise DeSalvo (Fordham University Press 2014).​