When Henrietta’s lover dies, she becomes Laura’s cabin mate. Henrietta has known a lot of people, many more than Laura, and they will visit, and there will be the element of disbelief that such intelligent, well-educated and even worldly people would live in a cabin that isn’t, despite what people expect and want for them, really a lodge. Didn’t their mother leave them anything? No, she did not. Nothing fell out of her pocket. It was empty when she expired.

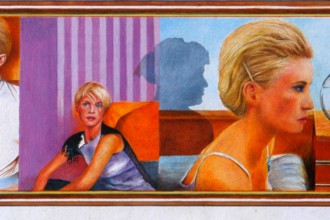

Laura is fifty-seven now. Her hips have spread but she still wears jeans well. She sits on the edge of her single bed and yanks them on from where she dropped them the night before. These days she’s illustrating books. There’s a market for books that capture feelings most people have but cannot express. Laura’s illustrations do that for them. She works a good part of the day on the second floor, which is a loft studio with two sky lights.

After she’s studied photographs of a bird, she makes sketches, and after the sketches, she paints. Through the day, dumpy Henrietta brings her snacks and looks at her work and murmurs both approval and disapproval. Henrietta is almost twenty years older than Laura, and there is no ignoring her reactions. She may know more than anyone on earth because she will admit to remembering what she thought as a man.

Eventually Henrietta slips on the rocks while going down to the creek where she likes to meditate. She hits her head and dies, and Laura faces the fact that she cannot invite all of Henrietta’s friends to the cabin for a memorial.

Manhattan becomes the place, then. Laura is no stranger there—she has a following in the publishing and art worlds—and Henrietta never lost the cachet of her sex transformation or significant jobs in politics and museums, so people, all kinds of people, more than two hundred come to the memorial and want to console Laura and invite her for a meal or a walk in the park and generally be kind.

Laura has inherited Henrietta’s semi-abandoned apartment and is 64 and uses it because she can’t otherwise keep up with the work thrown her way in New York. Even back in the city, she retains that nature girl way about her, the sun- and wind-parched skin, the strong hands, the habit of seeing scenes in people’s eyes that they want her to paint: dunes, a riverscape, a red tail hawk on a power line surveying a purplish field of dry grass for quarry. They tell her it’s poetry. She must write it down. She makes a face. What is it about people who can’t think without words? This weekend she is going up to the cabin. That’s poetry. Liberating Zack’s truck from of the city and parking it forever by his hidden grave, that’s poetry.

But she looks at her fingers and wonders about splitting wood. They’ve grown soft. And she thinks about her energy level. Does she really want to drive that far? What about an early dinner, a little too much wine, and maybe a man who diffidently will let her know what men want women to know?

She finds that last thought trite, but it is precisely her indifference to men in their sixties that keeps them coming. Now, after all these years, they dare to be interesting. That’s not easy but she lets them try, and tonight this man recites passages from Thomas Hardy’s poetry, and it works.

So we are going to see a late in life affair blossom and burn for a dozen years and then his death in Sloan Kettering.

We are going to see Laura come out on the sidewalk and choose to amble a few blocks by herself before hailing a cab, and then we are going to see Laura begin to cry and the driver look at her in the rear view mirror and not mistake her for a mental case.

She’s a beautiful old woman, her white hair thick and braided, her face partially covered by her tree root fingers, but only partially because she is unabashed about meeting the cabbie’s eyes in the rear view mirror with her own. She wants to see him see what appalls her: she is not through yet. She will live on. And eventually she will tell him where she wants to go.

Robert Earle is one of the more widely published contemporary short fiction writers in America with more than ninety stories in print and online literary journals. His new novel is Suffer the Children. He lives in North Carolina after a diplomatic career that took him to Latin America, Europe, and the Middle East.