A writer remembers the legacy of his grandfather in a brief biography of the man’s lifeÂ

by Robert Boucheron

Pierre Boucheron, my grandfather, was the first advertising manager of the Radio Corporation of America under David Sarnoff in New York City in the 1920s. Born in Paris, France in 1889, at the age of ten he emigrated to the United States. In a letter to his younger brother in 1970, he writes: “Our poor mother had us in several farm homes, then back in Paris with our godmother Madame Obrenski, who helped her for passage moneyâ€. They boarded the SS La Champagne on August 26, 1899, and they arrived in New York on September 3.

Pierre Boucheron, my grandfather, was the first advertising manager of the Radio Corporation of America under David Sarnoff in New York City in the 1920s. Born in Paris, France in 1889, at the age of ten he emigrated to the United States. In a letter to his younger brother in 1970, he writes: “Our poor mother had us in several farm homes, then back in Paris with our godmother Madame Obrenski, who helped her for passage moneyâ€. They boarded the SS La Champagne on August 26, 1899, and they arrived in New York on September 3.

The SS La Champagne was a regular French Line ship, one of four steel-hull steamships put into service in 1886. It made many crossings from the French port of Le Havre to New York, but in 1915 it sank in a storm at the port of St. Nazaire.

The poor mother was Marie Louise Florizelle, originally from the département of le Hérault, of which the largest city is Béziers, in the south of France. She explains this in a letter to Pierre in 1929, handwritten in French. He describes her as a modiste, or milliner. She was to start work at Simpson & Crawford department store on Fourteenth Street and Sixth Avenue in New York. It is likely that she was a widow.

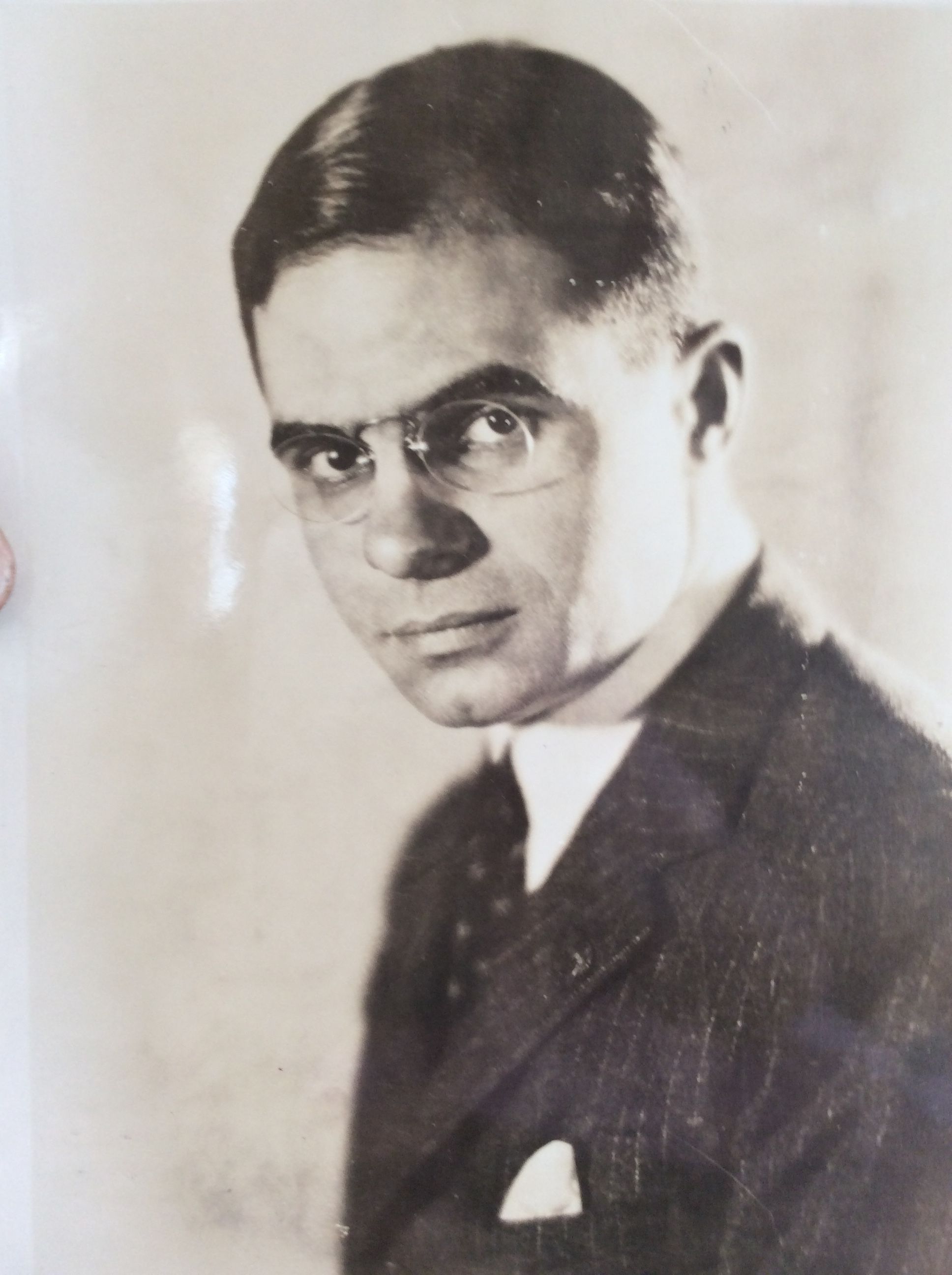

While on board ship, Marie Louise met a Swiss chef named Paul Simon Roggo. A widower with two young daughters, he also was emigrating to America. The young single parents married soon after they arrived. There is one studio photograph of each, probably from the early 1900s. Marie Louise bears a strong resemblance to her son. Pierre says that soon after they arrived in 1899, he witnessed a parade of veterans of the Spanish-American War of 1898 on Fifth Avenue, and that he knew no English.

The blended family lived in Philadelphia, where Roggo worked in hotel kitchens and clubs. He sometimes brought food home. The children attended public schools, where they learned English. Briefly, the boys attended Caswell Academy Hunts Point, New York, a military school, perhaps in 1902. The box of papers from my grandfather has drawings from school signed “Pierre Roggo†and dated 1903. There is no record that Pierre graduated from high school. Instead, he started work at age fourteen with “J. Habisreitinger, Fursâ€. In a letter to Col Quinton Adams, USN Ret., dated September 18, 1962, he writes:

“My first job was as a furrier’s apprentice in Philadelphia with an old friend of Mr. Roggo from Switzerland. It was a nice, easy job from 7 AM to 7 PM. My tasks combined cleaning boy, errand boy, moth-proofing the furs in storage, and caring for the horses and carriages of the mesdames and mistresses of the plutocrats and politicians of the era, while the ladies were being fitted with sealskins and sables.”

Pierre wrote a list of jobs, places where he worked. The list has thirteen more names in Philadelphia, including Hartel & Deppe Tailor, Baldwin Locomotive Works and Stenton Hotel, where he was a bellboy from March to September in 1907. Around 1906, Roggo and his family moved to Texas and then California, while Pierre stayed behind. In 1907 or 1908, he moved to New York City.

Starting in 1903, Pierre learned Morse Code, the basics of physics, chemistry and electricity, and how to build an electrical apparatus. He kept small notebooks, where he neatly copied mathematical formulas, wiring diagrams, charts, tables and data.

Radio, which was then called “wireless telegraphâ€, was cutting-edge technology, something like computer software today. Amateurs and inventors held the field. Each young man built his own transmitter-receiver with two call letters. Pierre did so with the call letters PX. About 1937, he wrote a piece titled ‘A New York City Amateur Wireless Operator of 1908’.

“The two illustrations shown here are of one of the first amateur wireless stations erected in New York City. It was located at 328 West 48th Street. Â Â Â

The transmitter consisted of a 1†spark coil, without any inductance or tuning whatsoever, connected directly to aerial and ground, and capable of reaching out to what was then the phenomenal distance of 25 miles.

The receiver was a simple tuning inductance with several forms of crystal detectors such as Perikon [trade name for zincite bornite], galena and carborundum. With this receiver, this amateur received naval and commercial stations from all over the United States.

Each night this experimenter copied the slowly transmitted press messages sent out by the Marconi Cape Cod station “CC†and thus taught himself to read the Continental code. The American Morse Code was also used in those days by American vessels, which code this experimenter also became proficient with.

On the operating table is shown a telegraph key and sender, which were connected with several friends located in the vicinity, that is, several blocks. The antenna was on the top of a five-story apartment house. It consisted of five strands of wire stretched about 100 feet and was particularly efficient for those days.

As far as this amateur can recall, there were four other amateurs in New York City at that time, with whom he carried on wireless conversations each night until 2 and 3 o’clock in the morning. These were George Eltz, Dr. Hudson of the DuPont Powder Works, the now famous Major Edwin H. Armstrong, and John Meyers.”

In 1908, Pierre started work as a “switchboard operator at the swank Racquet & Tennis Club on Fifth Avenue where I got $30 per month and mealsâ€. (Letter to Col Quinton Adams) The club was then located at 27 West 43rd Street. He stayed at this job for four years. In 1912, he wrote a self-description in a typewritten piece titled ‘Snobs and Flunkeys, some experiences and impressions gathered while at the R. & T. Club’.

“Oh yes, I almost forgot to mention Buckman Pete, sometimes called “Wirelessâ€. He was a swarthy and sinister-looking, old-young man who claimed French birth, but who really looked more like a hypothetical brew of a Greek and a Spaniard. A tennis marker once christened him “Yellow Bellyâ€. Pete was a common bellhop, the black sheep of a respectable family, and had once studied wireless telegraphy. You will agree with me that Pete was no ordinary individual with the above qualifications. How he ever came to the “Q-T†asylum no one knows but himself. Probably the monthly sight of thirty real simoleons turned his head.”

By June of 1912, Pierre obtained a license as a radio operator. In this year, he started work as a telegraph operator for the Postal Telegraph Company in New York. He called himself and others “brass pounders†for the brass telegraph key they used. Later in 1912 he joined the Marconi Company, founded in Britain as the Wireless Telegraph & Signal Company by the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937). The job was to operate radio on ships sailing the Atlantic coast of the United States, the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico, for four or more steamship companies. He called the ships tramps, freighters and banana boats, from the cargo they carried. His first ship was the SS Camaguey to Cuba, starting on September 3, 1912. He wrote a list of eleven voyages, some of which were on the same ship — Camaguey, Sabine, Mexico, Byron, Lenape, Comanche and Lampasas — ending on November 30, 1916.

Photographs of Pierre in these years show him on the deck of a ship. He is a good-looking young man of medium height, with a dark complexion that contrasts with his white uniform. He never smiles. This is true of all later photographs. With autobiographical writings, they suggest a serious, even brooding temperament.