A writer remembers the legacy of his grandfather in a brief biography of the man’s lifeÂ

by Robert Boucheron

Pierre Boucheron, my grandfather, was the first advertising manager of the Radio Corporation of America under David Sarnoff in New York City in the 1920s. Born in Paris, France in 1889, at the age of ten he emigrated to the United States. In a letter to his younger brother in 1970, he writes: “Our poor mother had us in several farm homes, then back in Paris with our godmother Madame Obrenski, who helped her for passage moneyâ€. They boarded the SS La Champagne on August 26, 1899, and they arrived in New York on September 3.

Pierre Boucheron, my grandfather, was the first advertising manager of the Radio Corporation of America under David Sarnoff in New York City in the 1920s. Born in Paris, France in 1889, at the age of ten he emigrated to the United States. In a letter to his younger brother in 1970, he writes: “Our poor mother had us in several farm homes, then back in Paris with our godmother Madame Obrenski, who helped her for passage moneyâ€. They boarded the SS La Champagne on August 26, 1899, and they arrived in New York on September 3.

The SS La Champagne was a regular French Line ship, one of four steel-hull steamships put into service in 1886. It made many crossings from the French port of Le Havre to New York, but in 1915 it sank in a storm at the port of St. Nazaire.

The poor mother was Marie Louise Florizelle, originally from the département of le Hérault, of which the largest city is Béziers, in the south of France. She explains this in a letter to Pierre in 1929, handwritten in French. He describes her as a modiste, or milliner. She was to start work at Simpson & Crawford department store on Fourteenth Street and Sixth Avenue in New York. It is likely that she was a widow.

While on board ship, Marie Louise met a Swiss chef named Paul Simon Roggo. A widower with two young daughters, he also was emigrating to America. The young single parents married soon after they arrived. There is one studio photograph of each, probably from the early 1900s. Marie Louise bears a strong resemblance to her son. Pierre says that soon after they arrived in 1899, he witnessed a parade of veterans of the Spanish-American War of 1898 on Fifth Avenue, and that he knew no English.

The blended family lived in Philadelphia, where Roggo worked in hotel kitchens and clubs. He sometimes brought food home. The children attended public schools, where they learned English. Briefly, the boys attended Caswell Academy Hunts Point, New York, a military school, perhaps in 1902. The box of papers from my grandfather has drawings from school signed “Pierre Roggo†and dated 1903. There is no record that Pierre graduated from high school. Instead, he started work at age fourteen with “J. Habisreitinger, Fursâ€. In a letter to Col Quinton Adams, USN Ret., dated September 18, 1962, he writes:

“My first job was as a furrier’s apprentice in Philadelphia with an old friend of Mr. Roggo from Switzerland. It was a nice, easy job from 7 AM to 7 PM. My tasks combined cleaning boy, errand boy, moth-proofing the furs in storage, and caring for the horses and carriages of the mesdames and mistresses of the plutocrats and politicians of the era, while the ladies were being fitted with sealskins and sables.”

Pierre wrote a list of jobs, places where he worked. The list has thirteen more names in Philadelphia, including Hartel & Deppe Tailor, Baldwin Locomotive Works and Stenton Hotel, where he was a bellboy from March to September in 1907. Around 1906, Roggo and his family moved to Texas and then California, while Pierre stayed behind. In 1907 or 1908, he moved to New York City.

Starting in 1903, Pierre learned Morse Code, the basics of physics, chemistry and electricity, and how to build an electrical apparatus. He kept small notebooks, where he neatly copied mathematical formulas, wiring diagrams, charts, tables and data.

Radio, which was then called “wireless telegraphâ€, was cutting-edge technology, something like computer software today. Amateurs and inventors held the field. Each young man built his own transmitter-receiver with two call letters. Pierre did so with the call letters PX. About 1937, he wrote a piece titled ‘A New York City Amateur Wireless Operator of 1908’.

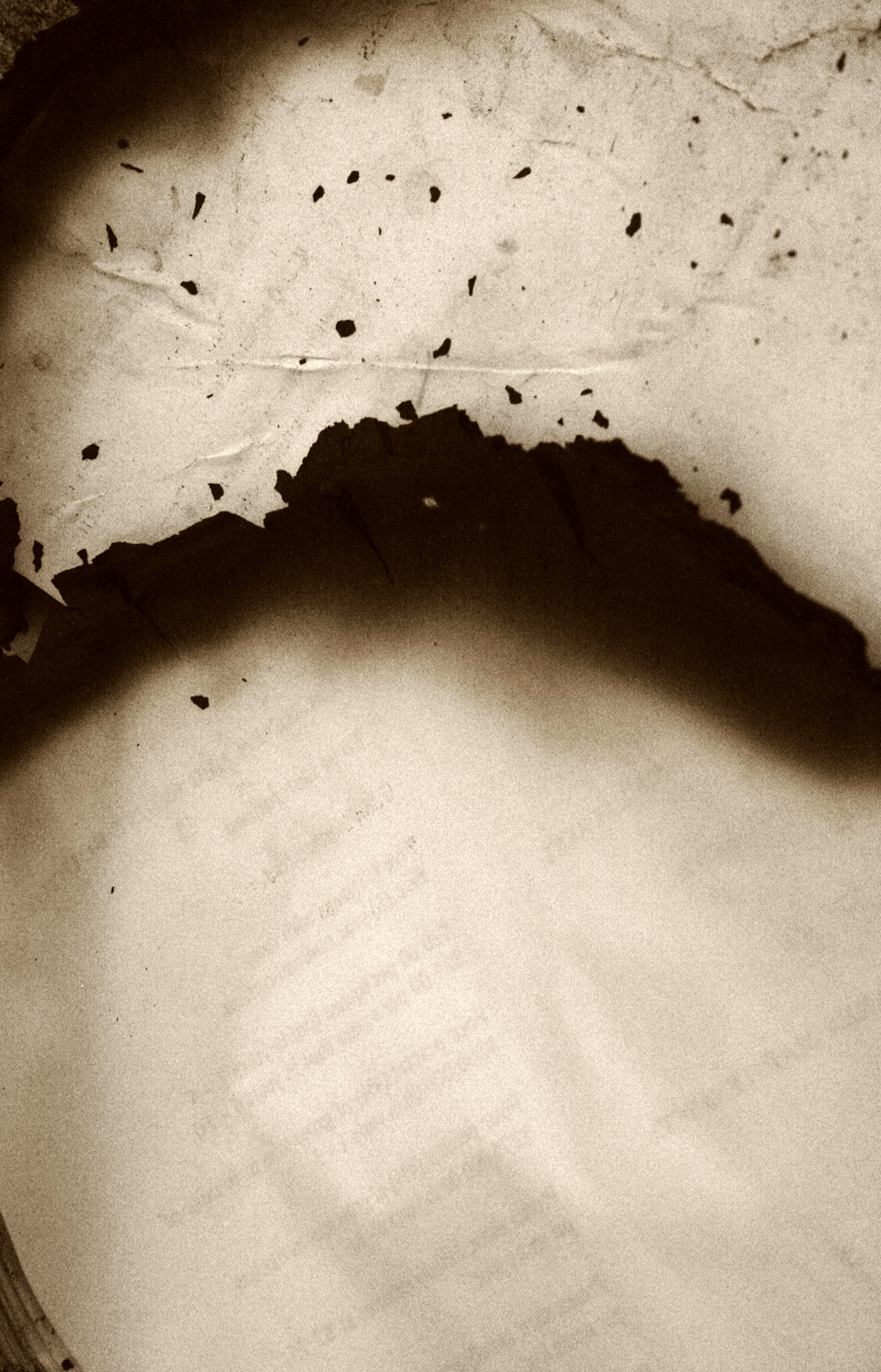

“The two illustrations shown here are of one of the first amateur wireless stations erected in New York City. It was located at 328 West 48th Street. Â Â Â

The transmitter consisted of a 1†spark coil, without any inductance or tuning whatsoever, connected directly to aerial and ground, and capable of reaching out to what was then the phenomenal distance of 25 miles.

The receiver was a simple tuning inductance with several forms of crystal detectors such as Perikon [trade name for zincite bornite], galena and carborundum. With this receiver, this amateur received naval and commercial stations from all over the United States.

Each night this experimenter copied the slowly transmitted press messages sent out by the Marconi Cape Cod station “CC†and thus taught himself to read the Continental code. The American Morse Code was also used in those days by American vessels, which code this experimenter also became proficient with.

On the operating table is shown a telegraph key and sender, which were connected with several friends located in the vicinity, that is, several blocks. The antenna was on the top of a five-story apartment house. It consisted of five strands of wire stretched about 100 feet and was particularly efficient for those days.

As far as this amateur can recall, there were four other amateurs in New York City at that time, with whom he carried on wireless conversations each night until 2 and 3 o’clock in the morning. These were George Eltz, Dr. Hudson of the DuPont Powder Works, the now famous Major Edwin H. Armstrong, and John Meyers.”

In 1908, Pierre started work as a “switchboard operator at the swank Racquet & Tennis Club on Fifth Avenue where I got $30 per month and mealsâ€. (Letter to Col Quinton Adams) The club was then located at 27 West 43rd Street. He stayed at this job for four years. In 1912, he wrote a self-description in a typewritten piece titled ‘Snobs and Flunkeys, some experiences and impressions gathered while at the R. & T. Club’.

“Oh yes, I almost forgot to mention Buckman Pete, sometimes called “Wirelessâ€. He was a swarthy and sinister-looking, old-young man who claimed French birth, but who really looked more like a hypothetical brew of a Greek and a Spaniard. A tennis marker once christened him “Yellow Bellyâ€. Pete was a common bellhop, the black sheep of a respectable family, and had once studied wireless telegraphy. You will agree with me that Pete was no ordinary individual with the above qualifications. How he ever came to the “Q-T†asylum no one knows but himself. Probably the monthly sight of thirty real simoleons turned his head.”

By June of 1912, Pierre obtained a license as a radio operator. In this year, he started work as a telegraph operator for the Postal Telegraph Company in New York. He called himself and others “brass pounders†for the brass telegraph key they used. Later in 1912 he joined the Marconi Company, founded in Britain as the Wireless Telegraph & Signal Company by the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937). The job was to operate radio on ships sailing the Atlantic coast of the United States, the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico, for four or more steamship companies. He called the ships tramps, freighters and banana boats, from the cargo they carried. His first ship was the SS Camaguey to Cuba, starting on September 3, 1912. He wrote a list of eleven voyages, some of which were on the same ship — Camaguey, Sabine, Mexico, Byron, Lenape, Comanche and Lampasas — ending on November 30, 1916.

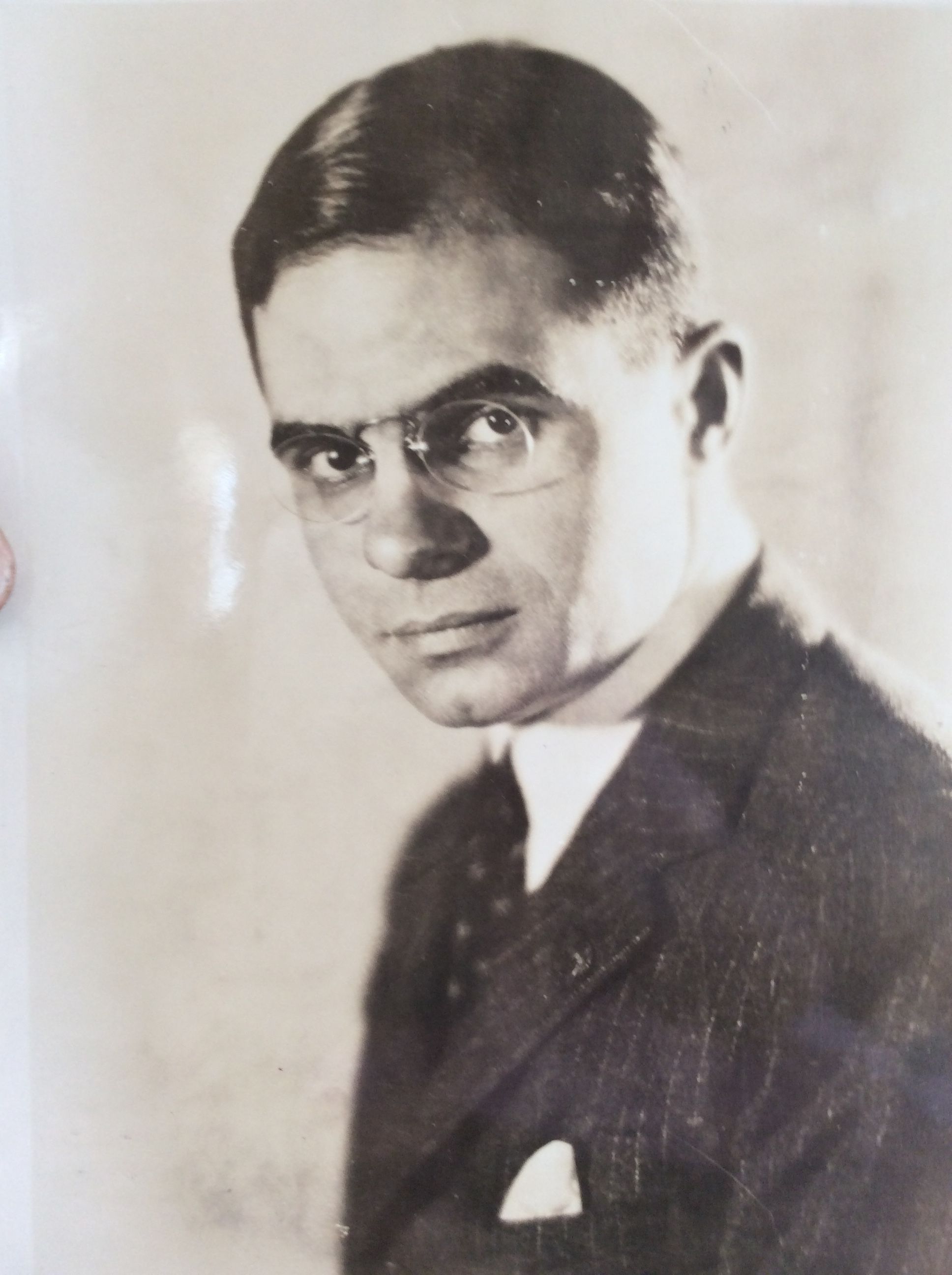

Photographs of Pierre in these years show him on the deck of a ship. He is a good-looking young man of medium height, with a dark complexion that contrasts with his white uniform. He never smiles. This is true of all later photographs. With autobiographical writings, they suggest a serious, even brooding temperament.

In the ‘World Wide Wireless’ of October 1921, however, he gives a facetious account:

“My set was located at 48th Street, NYC, and at this strategic point I most effectively jammed “Pick†at “WA†(the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel’s station), as well as our present assistant treasurer, Mr. Payne, who was then chief operator at “NY,†42 Broadway.

In 1914, Pierre happened to be on a ship in the harbor of Vera Cruz, Mexico. The Mexican Revolution of 1910-1920, and a German overture of alliance with Mexico, had strained relations with the United States. In April 1914, Americans were evacuated from Mexico City, and American warships shelled Vera Cruz. Refugees crowded aboard American ships, which took them to New Orleans via Galveston, Texas. Pierre wrote three eyewitness accounts of this episode, one titled ‘The American Occupation at Vera Cruz’. He took photographs and bought picture postcards of the damaged town and its people. As a radio operator, he was apparently pressed into service with the United States forces.

Another glimpse into this period comes from ‘The Story of a Naval Reservist’, notes written during 1949 for a projected book.

“In 1914, I am at sea on board the British luxury ship the SS Byron. A close call when we are intercepted by a German cruiser off the coast of Brazil, whose skipper did not know that war had been declared between England and Germany. Wireless was pretty unreliable in those days. On return to New York, I try to join the French naval forces, but a consular bureaucrat discourages me, so I apply for U. S. citizenship and forsake France forever.”

From 1915 to 1917, he took three correspondence courses in business English, to make up for a lack of formal schooling. “Later went to NYU and Columbia for special courses in writingâ€, he wrote. He repeated this claim in published profiles, but it may be an exaggeration. On May 24, 1916 in New York, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

On December 5, 1916, Pierre started work as a “correspondent†for Montgomery Ward Company in New York. Today we would call this kind of work direct mail marketing. He describes it in 1942 in the “Prologue†to his Greenland book.

“It is the year 1917. The month is April. There has been some sort of a shamble war going on in Europe ever since August 1914. My adopted country, the United States, has been trying hard to keep out of that war, and President Wilson has been reelected on the platform of “He Kept Us Out of Warâ€. But it looks mightily as if we shall soon be in it. An organized naval reserve is in the making. At age 26, already a seagoing veteran and minor participant in the Vera Cruz occupation of 1914, I think I had better get into a branch of the service I am best fitted for.

At this time I am holding down a very prosaic desk job learning the mail order business with Montgomery Ward. I have visions of a dreary future rising from a correspondent at $16 per week to assistant superintendent of correspondence ten years later at the larger remuneration of $25 per week. A colleague sits next to me grinding out 125 letters a day to New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania farmers telling them how to buy farm lighting plants, silos, and living room suites on easy terms.

One day, he shows me a brand new passport and his number as a volunteer ambulance driver with the French Army. He is a slightly built young fellow, a Yale graduate who is going in for serious writing when the farmers’ problems ease up a bit. He wears pince-nez myopic glasses and has been rejected as a volunteer in our own army long before there is talk of a draft. Here is a native-born American who is anxious to be off to the wars to help my native France. I will be a slacker if I do not do something about it. I feel pretty low down. My beautiful stenographer stops saying “good morning†to me.”

Address books from this time contain names in Paris, including some Boucherons, two of whom are in infantry regiments. Did Pierre write to them? There is also an entry for:

Corp. J. E. Boucheron

80th Field Artillery

Battery D – 7th Division

American Expeditionary Force, France

This could be his younger brother Jean Edouard Boucheron, born in 1893. If so, Pierre had another reason to feel like a “slackerâ€. Why did he not enlist in the regular army or navy? He wore glasses, so there may have been a medical reason. Instead, he took a step that would be decisive for the rest of his life. From ‘The Story of a Naval Reservist’:

“I join the USNRF (You Shall Never Reach France) on May 1, 1917 as an Electrician (R) 2nd Class. As such, I instruct a mixed class of ensigns, lieutenants and “strikers†for radio. I make 1st Class, then happiest of days, I am a CPO!”

The initials stand for United States Naval Reserve Force, which soon lost the final word. He was an instructor at the United States Navy Electrical School in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. To judge by this, and later comments, he sought promotion. From June 19, 1917 to January 22, 1918, he served as Chief Electrician on the USS Aloha, under Admiral Cameron McRae Winslow (1854-1932), who had been recalled to active duty. From ‘The Story of a Naval Reservist’:

“We cruise within the twelve-mile limit off the Atlantic coast. Admiral Winslow comes aboard his flagship as Inspector of Naval Districts. I meet a descendant of Vikings in the person of E. J. Hendrickson, Chief Yeoman USNRF. The influenza of 1918 nearly decimates the entire crew at Norfolk Navy Yard.Â

I stagger into the Navy Department at Washington, meet the Chief of Naval Aviation, Lt. Towers, now Vice Admiral, who turns me down for overseas duty as a naval action observer. Whereupon I wind up again at Building 1, Brooklyn Navy Yard, as an inspector-investigator of illegal wartime radio activities. I am appointed a Warrant Gunner (R). Repeat travel orders from Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels. Reunion with the wireless operator clan of Horn, Muller, King, Eltz, et al.”

In the “Prologue†to the 1942 Greenland book, he gives another account of this period. After the stenographer snubs him in 1917:

“The next day, I enroll in the United States Naval Reserve Force as an enlisted radio operator. I wait a shameful month before I am called to duty. Finally I am assigned to a seagoing war vessel and shortly thereafter made an officer. Since the ship I am on does not rate a specialist officer, I have to go back ashore to round out the war as a sort of illegal radio station sleuth. My job consists of running down crackpot reports from would-be patriotic informers. In every loose wire hanging from clothes line poles in the city, and in discarded rural telephone lines in the Adirondack Mountains, they see a German spy radio station.

‘We are at war’, my superiors warn. ‘You never know. One day a real spy will be caught red-handed with codes and ciphers and a 50-kilowatt transmitter hidden in a corn crib. All reports must be investigated.’

I never catch even one, lone, 110-pound scoundrel. Oh, the shame, the ignominy, the ingloriousness of this duty!”

About this time, he lived at 20 Fulton Street, Maspeth, New York, then moved to 147 Pierrepont Street, Brooklyn, New York. He spent “three months at a U. S. Navy school to study navigation, international law, and naval regulations . . . a sort of cram courseâ€, and took a qualifying examination. On February 17, 1919, he was promoted to Ensign. In August 1919, he was released from active duty. He wrote about his experience in a four-part article ‘Radio Detective’, published in 1920 in ‘Electrical Experimenter’ magazine.

He traveled for this work, perhaps as far as Hartford, Connecticut. On October 16, 1919, he married Wilhelmina Herman, who lived in Hartford. Ten months older than he, Wilhelmina was known by the nickname “Billie,†and later to her grandchildren as “Dodieâ€. She came from a large family of German-Americans. Her mother Helen Hoffman had been born in Germany and brought to the United States as a child. Her father, Frederick Herman, was a textile designer. Wilhelmina graduated from high school, what is now Northfield Mount Hermon, and she worked as a secretary. Bride and groom were both thirty years old on their wedding day.

The marriage was troubled, perhaps from the start. Wilhelmina had a strong personality and a sharp tongue. In 1960, she lived near us in North Syracuse, and after a fall that broke her hip, with us. As a child, I combed her yellow and white hair while she told me about her childhood and early adult life. One scene featured her husband in a rage — he picked up a “butcher knife†and chased her. She was indignant about his affairs with other women. Although he asked more than once for a divorce, she refused.

By 1920, the couple lived at 328 Carmita Avenue, Rutherford, New Jersey. Income tax returns for 1920 and 1921 show this address. There, on September 11, 1921, they had a son, Pierre, Jr., who would be their only child.

Robert Boucheron is an architect in Charlottesville, Virginia. His stories, essays, poems and reviews appear in Bangalore Review, Gravel, Grey Sparrow Journal, Milo Review, New Haven Review, North Dakota Quarterly, Poydras Review, Short Fiction, The Tishman Review.