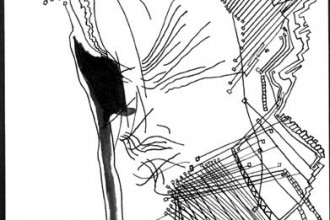

Death of an Artist by Sausan Saulat. Image Courtesy the ArtChowk Gallery.

There is a way to grow old. It isn’t time for you to learn yet, Maa says. That perhaps could be another reason why birthdays make you unbearably sad. Answer midnight calls, thank everyone for the wishes, throw a party in the evening, have friends over to partake in the leaving of a year behind, make merry and see the evening off. Along with it, you also let pass the realization that the true purpose of the body is to disintegrate. The next day, you wake up a year older, and find your mother, who’d never made a sound while sleeping before, suddenly breaking into loud heavy snores. You fear she’s growing old. Her vocal cords, you think, have calcified without the knowledge of luster. You make a mental note, lying by her side coiled like a foetus on the other bed. Her breath rises with ragged amplitude, knocks off the cold air of the room and falls discordantly. You turn, watch the movements of her chest. A dark outline, an inverted parabola rises like a tide and recedes to the coast of her body. Slowly, you gather, time doesn’t wait for the revealing of truth. And that is how you learn to imagine your mother’s death.

For all practical purposes, it can be a heart attack or an allergic reaction. Maybe a fall from the stairs or plain old age. Maybe guilt corroding into her skin or perhaps the shock, from which she will never be able to emerge, when I will tell her the truth. But what if by the time I decide to tell her, she has already left? In fact, going by the logistics of my imaginations of her death, she was already meant to leave before I would meet Bipul in Bhomoraguri, just by accident over a cup of tea. Meant to leave before he would lecture me on the smallness of the town I live in. That some places are meant to be left behind, he’d say. The North East of all places is one. For it only forced him to flee. To another world. Another life. Though he had spent a large portion of his childhood there. She was meant to leave before he would tell me that I was different. That I deserved to have an identity. My own politics. My stand. And not lose myself it in the garb of being a victim of conflict. Of bullets and bomb blasts. Of being called “chinkis” and “separatists”. Meant to leave before he would drag me to the mighty red river bleeding before my eyes, my Brahmaputra, on the banks of which I had grown up listening to the dirges of the fishermen. And how he would reveal, that to flow was to waste. Only the dead floated, he’d say. That I could choose to be alive, choose over a life away from the mountains, away from the hills – the ruins of Bamuni, the caves of Nilachal – where my echoes would be heard and not put behind bars. Meant to leave before he would leave me stacks of letters, still littering my bed, his love beaten into every word, his yearning woven into them. Meant to leave before he would call up and plead for the last time: Pranjal, this world will never understand. There’s no point waiting. Just come down soon. But she didn’t. She had to wait till I left.

Right now I am hurtling through the proverbial crazy Mumbai traffic, sitting in a tethered auto rickshaw. There are so many of them waiting in line to depart. I wonder how motion is the greatest challenge and yet a never-failing business. All of us want to move, to drift, and to change. To reach somewhere, we do not know. It’s a chiaroscuro of city lights that guide me at the moment. They seem to dance to Kishore Kumar’s chalti ka naam gaadi plugged in on a loop, booming from the jukebox below the steering-handle. It’s a good device to escape the honks blaring from everywhere. A device to soothe the anxiety and the wait you often feel while moving through unknown cities: that before you reach almost everything would be finished. For no real reason; except the conditioning of the fear that it is easier to get killed or lose your loved ones to death in bigger cities. But then, some people do not choose to die anywhere else except in their homes, Maa says. I refuse to die anywhere else except the bed in which your father breathed his last. Assamese mothers are a little too dramatic. That is true. Ours is a slow-sad race. Withdrawn and cornered. We certainly have reasons to complain. Years of violence do leave traces, don’t they? Though it isn’t quite there anymore. No ULFA, no SULFA, only NDFB, KLNLF, NSCN, NLFT, and so on. But these men are fighting for a greater Bodoland, a greater Karbianglong, a greater Nagaland. No, not any greater Assam. That dream is forgotten by now. Hence we Assamese mustn’t worry. We belong to India and can remain herein. Our mothers like other Indian mothers can afford to be sad, dramatic and sentimental. They can die peacefully.

But for now, home is too far. Maa is already on the train back to Bhomoraguri. I’ve seen her off at the station, and still haven’t told her the truth. Perhaps she’ll know of it through a letter I will send her, months later, from Dartmouth. In it, I will write to her that I want to return. Perhaps she will only know of my missing her and be overjoyed, and not the other half of the story. I, perhaps, will not tell her anything about it, not plagued by the fear of being branded as a criminal but by the fear of breaking her heart to death. But as I’ve said, for now, home is too far and I can let my imaginations rest for a while. At least until I reach the place Maa and I were staying in. I need to pack my luggage and reach the airport by 11:00 pm. The flight is at 1:30. And I’m worried; it’s a long way from CST to Kandivli. The roads are jam-packed. I don’t know if I’ll reach on time. I also need to send a mail to Bipul informing him of the flight details. I have a habit of leaving things to the last minute. I’ve always believed in the art of slowness. Bipul doesn’t like things late. He’s been conditioned to be ambitious. To run. To rush. To flee. But is an ambitious man, in truth, capable of love? Perhaps not. For the very night I will land in Hanover and make love to him, I will smell something tepid in his breath. His movements will be stiff and his hands will not search for things a man grapples to relocate in a lover’s body – with a hopeless anxiety – having him in his arms after long. I will only feel his measured arms around my body in a clumsy embrace. Night after night. And the more he will re-assure me every morning of his growing tiredness and the stressful immigrant experiences, the harder I will find it to forgive myself for leaving Bhomoraguri, and to believe that the delusion of love is capable of survival beyond physical closeness.

Four months after my arrival, it will begin to snow in Dartmouth. And one day while returning from the university, suddenly in that unrelenting cold, I will be plagued by the memory of a poem on “the thing about leaving”. I will not be able to recall the title of the poem. Will not be able to recall the boy’s face who had gifted it to me. But just that he was one of those many who would fall for their seniors in school. Boys who’d be shy and withdrawn. And perhaps fearful they felt differently from the rest of the world. Boys who’d eventually learn to pine for men reading poets who wrote of their troubled homelands and the inability to return. Poets who wrote of the ultramarine waters of the Jhelum and the snowcapped Himalayas. Poets who wrote of the fabric of Cashmere, the songs of Begum Akhtar, and of dead post offices and mailmen. But that will be all from a remote memory of my seventeenth birthday. And when I will tell Bipul about it, he will listen coldly and ask me to take a break if I feel the need to. Go for a month and come back. And if all these things happen too late, after I’ve exhausted my imaginations, after Maa has passed away, I will perhaps not return. Or take a break.