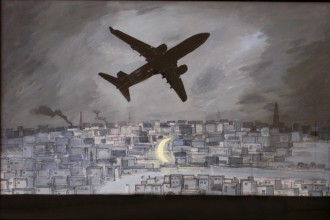

Muraqba II by Syed Sajjad Hussain. Image courtesy ArtChowk the Gallery.

I remember it was in the leisurely residue of my vacations from boarding school that Father thought it appropriate to take me as an intern at his tuck shop in the Al-Jannah Pharmaceutical Company.

The ‘shope’ – as Father called it – comprised one refrigerator, a tea-maker, one broad shelf, and a counter. It was located in the factory basement in a spacious lunchroom strewn with chairs that looked smaller than the ones in our classrooms but seemed to accommodate much bigger people. Coming out of the elevator, the shop was the first thing one noticed on the right. Father introduced me to the staff as ‘Taaj-theen’, instead of ‘Taaju’ that everyone at home was accustomed to calling me.

I was to only observe and watch Father and receive instructions from him for the first week. On my first day, I noticed that he was much more respected at home than at work. Here, he was not addressed as ‘Haaji[1] saahib[2]’ and no one stood up to greet him. Father handed me a list that contained the cost of every item, which was slightly higher than the retail price printed on the wrapper. As I was learning these augmented rates, a boisterous man in his early twenties emerged barefoot from behind the elevator frame and started dragging all the chairs and tables, ramming them into the far left corner of the room. He was quite rangy and sported a peculiarly broad grin between a pair of sunken cheeks, complemented by two protruded cheekbones. He, I later discovered, was the canteen attendant Yousuf — euphemistically called ‘office boy’ — who did all the menial chores except for dishwashing. He was neither a boy nor did he have anything to do with the offices, though, which were situated on the upper floors of the building.

As the chairs surrendered to his brutish lunges, the peculiar grin stayed on his face. In a matter of minutes, the whole thirty-by-thirty room stood stripped to a vacant expanse of grey tiles.

Every day, I would greet customers, hand over their desired items, obtain the augmented prices, and add their entries in the journal.

Father handed me another list to go through; this one was of vendors and their contact information. When I happened to look again, Yousuf’s exuberance seemed to have evaporated and he was diligently swabbing the floor, though it had been mopped twice already. He then tied a handkerchief around his head and began to unroll the prayer mats that were stacked behind the elevator frame, all the while mumbling something to himself. He exuded a solemnity that belied his oafish excitement displayed a while ago, meticulously laying the mats and taking special care of their alignment and evenness.

“Oh paagla, siddhi ker, oaye!â€[3] Yousuf frowned and yelled to the janitor assisting him. Then he knelt down, his head bent, his eyes riveted to the prayer mats, and languidly crawled along their perimeter with the devotion of a pilgrim ascending the Scala Sancta. He was caressing the mats with an air of sensuous reverence to iron out any remaining folds that I thought only he could spot.

For some reason, customers rushed in most swiftly right before the call to prayer. Once I had attended to all of them, my eyes looked for Yousuf, seeking the resumption of the ceremony I had been witnessing. Instead, the more formal ceremony had commenced: the imam presiding over the congregation. To my bewilderment, Yousuf stood away, rearranging the strewn shoes to make way for incoming worshippers. He still had that mysterious solemn smile — the dangling concave curl of his dark lips, hooked to the pit in either cheek.

This was how he singlehandedly transformed the canteen into a mosque four times a day- every day, seven days a week. The reversion back to — or the conversion to — the canteen seemed to be done with the perfunctory professionalism with which we all worked. I began to enjoy this routine. Every day, the imam with his hefty paunch would descend from the elevator, glance first at the impeccably laid prayer mats and then at Yousuf, and take his position adjacent to the front wall, facing the Qibla. Every day, Father would desert everything and scamper towards the imam to shake the cleric’s hand with both of his. Every day, Yousuf would repeatedly obliterate and recreate the mosque. Every day, I would greet customers, hand over their desired items, obtain the augmented prices, and add their entries in the journal. In times of leisure, I would read Gulliver’s Travels, much to Father’s displeasure. Every evening at six, I darted to Father’s motorcycle to go home, as Yousuf and his mates stood with their arms raised in front of the guards, getting their pockets turned out and the garbage bags rummaged. The first day when I followed suit, the security guard tapped the back of my head and said, “Aap jaayen, beta ji[4].â€

Often a woman in a black abaya standing at the bus stop adjacent to the factory would smile at me and I would wave back.

[1] One who had performed the Hajj at least once. [2] An Urdu/Punjabi suffix depicting formality. The equivalent of the prefix Mister. Also used by servants to address their masters. [3] “Oaye – A Punjabi interjection, chiefly used to show extreme informality or to warn/accost someone – straighten it, you madman!†[4] “You go, dear son.â€