By Christine Jin

“This man of mine may kill me,†reads the last entry in a missing wife’s diary. Suspicion descends on the husband, but when he realizes it’s the wife’s sickening ploy to punish him, he begins the fight back. Gone Girl is about a battle of the sexes taken to a whole new sickening level, and it excels at black comedy, among the many genre masks it dons. Wife and husband compete for the favor of judging spectators, and the camera often swaps between the two parties as one is interviewed on cable television and the other watches and responds. But the film hardly cares if exactly the right balance exists between them, especially in the severity of the harm they face. Whoever wins doesn’t expect to get cheers, though the psychopathic one will obviously inspire much more aversion and fear than the merely lazy, cheating, moronic one ever could. Based on a controversial yet wicked farce by Gillian Flynn, it rather revels in the asinine proceedings of a trial of marriage under this diabolic woman’s thumb.

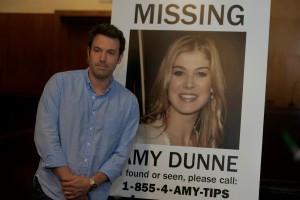

In David Fincher’s usual slick hands, a desolate Missouri suburb — in which Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike) rouses the latent fervor of gossipy tongues and blood-sucking media — gains a plastic countenance. Neighbors’ homes are spaced apart just enough to remain at once private and watchful, while the Dunnes’ dollhouse is a bit too grandiose and glossily furnished for a cozy home. Adding to this façade are Amy’s diary flashbacks, which rebuild the early parts of the Nick-and-Amy fairytale on a softened, sweetened urban land. Her velvet voice intermittently dishes out a mixture of truths, half-truths, and lies, while in the (relatively) real world, the couple’s anniversary ritual of treasure hunts mutates into the whole town’s organized search, and then into a national pastime of finger-pointing.

The searches and Amy’s narration alternate and coalesce in a way that turns everyone within the movie against Nick (Ben Affleck), though for us audiences outside of it, the wife’s complete victim status isn’t so convincing. Our knowledge of outcomes of the investigation (as Amy intended) and the history of the couple’s relationship (as Amy fabricated) builds up piecemeal. Static shots and quick cuts typical of Fincher’s style impel us to take in a discrete bit of information from each shot. This sort of data pickup process is a corollary of a heightened version of continuity editing, which reinforces the immediacy of each individual shot and its impact on the characters and viewers alike. In an interrogation scene, for instance, where the detective Rhonda grills Nick with his lawyer present, it’s all a constant snappy to-and-fro of shots each containing a single line/question or a single reaction/answer. Unsurprisingly, the rhythm of the scene recalls the dialog-heavy depositions in The Social Network. In fact, a few — and long by Fincher’s standards — two-shots in a bar conversation in SE7EN between rookie and veteran, which make their dynamic feel less mechanical with varying camera distance and more breathing room, are kind of a rarity in Fincher’s works. But as in the case of The Social Network, the director’s M.O. admirably fits Gone Girl’s wryly staged, nippily-paced narrative.

So after all this ruckus of phenomenal proportions, who wins the battle? It’s both tempting and, for some, disturbing to call out the wife’s name. This truly evil “psycho bitch†doesn’t receive the sort of judgment meted out to her forebears 20 to 30 years ago. Alex, for one, from Adriane Lyne’s Fatal Attraction, is a single career woman — thus damningly flawed by society’s yardstick — whose villainy gets subsumed under her married lover’s trajectory of restoring his perfect home as crystallized in the movie’s final close-up shot of a family photo. Suzanne, another blond “psycho bitch†from Gus van Sant’s To Die For, gets buried under a frozen lake as punishment for killing her husband who found her career aspirations undesirable. The point is not that these villainies themselves are excusable, but that these female characters are created in their respective stories specifically to represent the vices that must be suppressed to reinstate certain putative virtues, i.e. patriarchy. In Flynn’s story, though, Amy doesn’t let Nick win; Nick has miserably failed in the role assigned to him when he made his vow, so Amy bends him to her demand that he return to his place.

Then, is hers a feminist triumph? Not really, but the same answer applies to the question of whether the movie is misogynistic. Distorted representations of women in film or in any other medium have always been, and still are, a pressing problem, and Gone Girl got a lot of flak for its portrayals of women, as well as the scenes where Amy utilizes the rape and domestic violence myths. Granted, Margo, Nick’s twin sister, despite being one of the strongest female characters here, resembles Suzanne’s sister-in-law, in that both are essentially the honorary males who supposedly offer the voice of reason, as opposed to the irrational female villains their brothers marry wrongly. But, given that all the characters operate on a pretty much surface level only, what you also get here is a diversity of females. When, after returning home, Amy relates her cobbled-together saga of survival surrounded by the feds, it’s only Rhonda, the female detective, who seems to see through the lies, while the male officers are mostly busy white-knighting and smoothing things over, instead of digging for the truth.

Amy’s tactics of using the egregious myths have understandably led to accusations of misogyny. Her strategy, however, also makes her perhaps the worst nightmare materialized particularly for peddlers of those myths, let alone ordinary viewers. Think of male psychopaths in sardonic tall tales who commit a variety of transgressions; they’d be regarded as pure evil, nothing more, nothing less. Amy, too, is exactly that — an evil mastermind who leverages the most horrendous methods to execute her grand plan and gets away with murder. Nick is a perfect match for her, since, for all his fatuousness, he eventually comes to his senses that his own narcissism can subsist only when there’s a woman like Amy willing to stroke his ego. A recession may have emasculated him a little, but this marriage must go on for the aforementioned reason. For Amy’s part, she isn’t a quitter, as she says at the end of the movie, and as long as she maintains authorship over her own Amazing Amy fairytales, her marriage will stay intact.

Christine Jin is a contributing editor for the magazine.