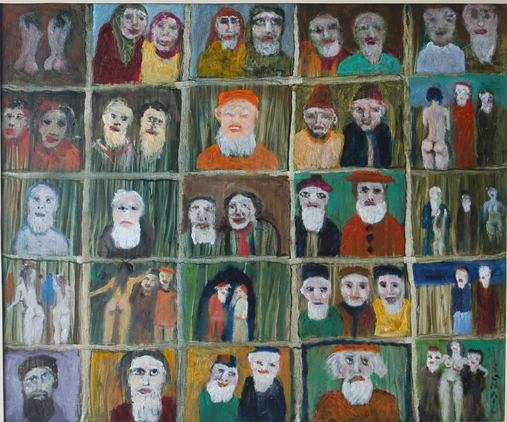

Strange World of Elderly People by Tassaduq Sohail. Image Courtesy ArtChowk Gallery.

A routine visit by a social worker turns into a budding friendship Â

By Vincent J. Fitzgerald Â

I stood at his door anticipating hostility and imagined him peering at my fish eye image.

“Who is it?”

The voice was jagged, projected from worn vocal cords, and angry.

“It’s Vinnie, from social servicesâ€, I whispered.

I thought my whisper may elude the attention of gossipers who hoped to sniff out a juicy story. Gossip doesn’t die of old age, and fear of broadcasted business coursed through the building when a social worker visited.

He opened his door just enough to allow a wedge of light to escape, and his cloudy eye inspected me through the slit. I learned his name from the building manager, but I was a stranger to him and he was clueless as to the purpose of my intrusion.

“What do you wantâ€, he growled.

“Hi Pat. May I come in?â€

“I don’t need anything. Who sent youâ€, he griped through what I assumed was a grimace on his face.

“Could we please talk inside? I would prefer to protect your privacy.â€

His privacy dangled before him, Pat granted me entry, if only to extricate me from visibility.

“Thanks for letting me in.â€

The rotund, bald man with a spotted, chiseled face, on which resided the crooked nose of a pugilist, looked just like he sounded. His braced knees seemed swollen, indicating the reason for his slow response time. He permitted me to sit on a beige, polyester chair in his dining room. Moving toward the chair, I crept around him and performed a subtle scan for filth or crawlers, indicators that he may be incapable of tending to his own needs, but his home was immaculate and warm. The earthy tones in his living room belied his gruff countenance, and the aromas of dark roast and burnt toast lingered.

“Your case manager asked me to see you.â€

Pat’s granite face contorted.

“That goddamn guy comes here and gives his card to the front office. Now everyone knows my business, and I don’t want anyone knowin’ my business.”

I hadn’t been scolded by anyone Pat’s age in a long time, so I offered an assurance to curry favour with him.

“I’m sure he’s just concerned about you.â€

Assurances sailed over the short man, and he moved to his phone with a speed not wasted on doorbells, impugning the manager with a harsh-toned monologue. I could have escaped then, but I remained, hoping to mend fences. After purging his hostility, Pat hobbled to his recliner and descended with a wince. His thick belly heaving through a white t-shirt, Pat began speaking as if reading his resume.

“I’m 83 years old. You see that kitchen floor?â€

The connection between the floor and Pat’s octogenarian status eluded me, but glancing at the kitchen tiles allowed for a break from his hard stare.

“I put that tile down myself. Took me all day.â€

I turned to look, and imagined the 83-year-old man labouring alone to lay three square feet of tile.

“They wanna have someone come in and clean. I don’t need anyone to clean. I clean my own things.â€

Each final word in his sentences was emphasized through wheezed breath.

“They want me to use a cane with four legs. Are they kiddin’?â€

Independence was a prized possession Pat was reluctant to relinquish, and I began to feel respect for him unlike any I had felt for a Manor resident before.

“I’ll tell ya’ what, when you need something, you call me.â€

That one simple statement of empowerment seemed to align us, and Pat’s face relaxed.

Now calm, he continued as if interviewing for a building superintendent.

“See that shelf where the coffee pot is?â€

My eyes split between a wall-mounted shelf and the loose skin on Pat’s extended arm where I imagined mammoth triceps once resided.

“My son put that up. I taught my boys to use their hands.â€

I wondered what it would be like to have skills passed down to me.

“I don’t need anything right nowâ€, he said with proud defiance, pointing at me with his right hand, his fingers formed into horns.

“Where do your sons liveâ€, I redirected.

“Down the shoreâ€, he responded in his smoothest tone.

Flooded by memories of the beach and the boardwalk in Keansburg, I tried to bond.

“You must know the area wellâ€, I offered.

“Sure. Point Pleasant, Long Branch, Keansburg.â€

I flashed back to long car rides with Springsteen sung over the sound of wind whipping through open windows.

“Wow, Keansburg? I spent summers there when I was a kid.â€

Arcades and backyard wiffle ball made Keansburg mystical. Mornings were peaceful and tinged with the scent of Taylor Ham, and night was brightened by boardwalk lights. I recalled pulling my dad, then letting go so I could dart into an arcade with the roll of quarters he gave me, my brown mop-top hair blowing, sweat seeping into my terry cloth tank top. Back then my mom and dad shared the same roof. They were still married, and we were a family.

“I loved it down thereâ€, I continued, now forcing words through my private reflections.

I recounted eating funnel cake amidst the clicking wheels and the bursting balloons of game stands. Pat cracked a close-mouthed smile, and then recalled a place I believed lived only in my memory.

“There was this place on the boardwalk. It looked old-fashioned. They boiled hot dogs in beer and you could smell‘em from the beach.â€

In an instant, I recalled the skunky aroma of Heineken on tap and the tangy scent of kraut-dressed dogs.

“Ye Olde Heidelberg!â€

My words burst like liquid in a shaken bottle.

“There you goâ€, Pat’s smile now revealed tiny, off-white teeth. His horned fingers darted with even greater emphasis.

“You know that place? I used to go there with my dad and beg to sip his beer.â€

On the outside I was sharing memories with exuberance, while secretly mourning those childhood boardwalk strolls with my dad.

“They had sawdust all over the wood floor.â€

Pat’s detailed memory belied his age.

“I used to pretend ice skate through it.”

Summers in Keansburg were the highlight of my year as the relaxed atmosphere led to relaxed rules. I was allowed to chase hot dogs with ice cream, and spend countless quarters filling balloons with a water gun. I did not know the word divorce. There was no second wife.

“Do you think it’s still thereâ€, Pat asked with a naïve hope that Ye Olde Heidelberg had been frozen in time.

“What about the old couple?†His questions bumped into each other.

The “old couple†was already old when I was a child. As I reminisced about sharing dogs with my dad, I speculated Pat remembered sharing them with his boys.

“The old couple passed years ago.â€

I feared the sad news would kill the smile and the moment.

“Have you gotten down there recentlyâ€, I asked.

“No, no. Not in a long time. Everyone’s busy.â€

I wanted Pat to be a have, and not discarded like a used hot dog doily.

Breaking our mutual reflection, I explained my need to see other residents, and asked Pat if he would like me to visit again, knowing he had met my needs more than I had his.

“Okay, Vinnie, Okay. Thank you, buddy.â€

I bristled as if being Pat’s buddy was an earned honour, and I wanted him to teach me to use my hands the way he taught me a person could want his “business†kept private, but his story told.

I left Pat knowing a trip back to Keansburg was as simple as ringing his bell. On the elevator ride down to the present, where the boardwalk lights were dim, and the sawdust was swept away, I wondered if I had ever stood in line behind Pat’s massive frame amazed by the thickness of his triceps. Maybe he nodded toward my dad in anticipation of a crisp Heineken while his boys and I made rainbows of ketchup and mustard. If our paths ever did cross it was long before busy schedules and second wives united us as have nots. I was comforted by our shared status, and my private assurance that Pat’s bell would ring a bit more often. He was more than an old man waiting to die, and he was more than his knee brace and fixed income. He was a story, a living narrative just a bit closer to completion. His story now having been heard, it was sure to live longer and I wondered if bringing him hot dogs would move him to teach me to use my hands the way he taught me to avoid prejudgement. Even if we exchanged only memories of boardwalks and beaches, I looked forward to relishing my visits to the buddy with whom I was bound by summers of arcade games, bursting balloons and hot dogs boiled in beer.

Vincent J. Fitzgerald is published in the Writer’s Circle Journal and the Fatherhood Anthology, ‘Dads Behaving Dadly 2’. Born and raised in Jersey City, he is a father of two.