Reviewed by Dave Coates

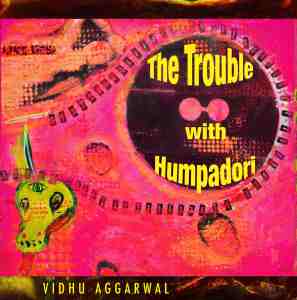

—Vidhu Aggarwal, ‘The Trouble with Humpadori’ (The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective, 2016)

‘The Trouble with Humpadori’ is a debut collection from Anglophone Indian poet Vidhu Aggarwal, published by The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective, a non-profit press for work by poets from India and the diaspora. ‘Humpadori’ is defined in a prefatory poem as “A performing cosmic deformity, singular and/or plural, male and/or female, taking on the shape of damaged icons and global commoditiesâ€. Given the sprawling, ambitious, nightmarish series of unsettling tableaux that follow, the level of preparation the text gives the reader at the outset is a blessing.

‘The Trouble with Humpadori’ is a debut collection from Anglophone Indian poet Vidhu Aggarwal, published by The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective, a non-profit press for work by poets from India and the diaspora. ‘Humpadori’ is defined in a prefatory poem as “A performing cosmic deformity, singular and/or plural, male and/or female, taking on the shape of damaged icons and global commoditiesâ€. Given the sprawling, ambitious, nightmarish series of unsettling tableaux that follow, the level of preparation the text gives the reader at the outset is a blessing.

The book is divided into twelve sections, each of which begins with a short conversation between an ‘Interlocutor’ — an affable, family-friendly 1970s chat show host-type with “protuberances and tails and jelly rolls hidden under that suit†— and Humpadori themself. These conversations (as with much of the collection) lean heavily toward the absurd, but contain oblique thematic directives for the proceeding poems. This overlying structure holds together the book’s imaginative playfulness, puts shape over a book in which the essential shapelessness of self is an animating idea.

Back in the preface, Aggarwal provides helpful touchstones for understanding what Humpadori might be:

“A portmanteau thought to be derived from the word hump (“a protuberance†in English) and aidoru (“idol†in Japanese). […]

the imperial-era English nursery rhyme ‘Humpty Dumpty’ about a broken egg-shaped figure who cannot be fixed despite the combined labor of “all the king’s horses, and all the king’s men. […]

the Greek symbol for the navel, omphalos, a round stone totem worshipped in ancient times. Similarly om (Sankrit), the sacred syllable and mantra for Hinduism and Buddhismâ€

These fanciful definitions turn out to be fairly accurate signposts for the book’s thematic concerns — the sexualised but disgusting body; the rupture in the continuity of self-definition in India caused by the destructive cultural and military forces of imperial Britain; a (probably) fruitless search for untainted spiritual peace. Behind the book’s garish high camp and delight-in-disgust is a sincere and inquisitive essay into how contemporary self-definition came to be uncontrollable, deformed and exaggerated on one hand, invested with near-endless possibility on the other. One of the book’s epigrams is a quotation from Dr Spock in the ‘Trouble with Tribbles’ episode of the original Star Trek series. Tribbles are ostensibly cute, harmless aliens (literally balls of fluff and not much else) which reproduce with disastrous speed. Spock, however, notes that “There’s something disquieting about these creatures.†Their featurelessness makes them impervious to reason, and their cuteness is diminished when they begin to pose a real threat to the Enterprise’s crew. One of ‘Humpadori’’s organising principles might be the deceptive kookiness with which it expresses its existential concerns; its aesthetic gaudiness at first seems brash and colourful, but over time seems increasingly oppressive and threatening:

“Whatever happens, you’re going to be fine.

Revulsion is not an option.â€

This dynamic of punishment by endless ‘freedom’ is at the heart of ‘Soap Friend’, a poem in the early stages of the book and one of its first clear indications that ‘The Trouble with Humpadori’ is not necessarily the ‘tilt-a-whirl carnival screw-ride’ one blurb promises. It’s more like forcing someone onto that carnival ride in full knowledge that they get motion sickness. In amongst the poem’s non-standard grammar is a rare moment of signal, a clear idea traceable from start to finish:

“You’re smarting and hence alive; you’re alive, so haven’t really been beaten.

Remember: the emulsion of alienation is luxurious, friend. I feel it all the time.â€

This line, taken in the middle of a poem that focuses on cleanliness (primarily of the conscience), which asserts “You are guilty of nothing, scrubbed // to the quickâ€, expresses a key microaggression suffered by a great many victims of racism — the poem’s assertion that “Little monster // it’s time to Dark / Continent with me†seems to signal its concern with the subtle rhetorical shapes made by white supremacy. The speaker clearly comes from a class that does not suffer the ‘beatings’ they mention; here, the voice of the oppressor defines the experiences of the oppressed. The poem exposes the fallacy that your suffering proves you are alive, but your survival proves that you cannot be truly suffering. The second line references the posture of victimhood white people often claim, that being criticised for one’s use of cultural power is as bad as having that power used against you: “Why apologize / for history?†What is left for the poet is:

“Now for some new hurt!—

A swill a-swallow, non-toxic sparrow      your servant of ever-diminishing returns.â€

The message, like all messages in ‘Humpadori’, is garbled and sensationalised, but the pain is palpable.

‘Humpadori Soldiers’ is one of many poems spoken by a narrative stand-in, a series of witness-poems that read something like origin stories or creation myths. Here, the soldiers attest that “Our song is a bog, and outfit of sink and preservationâ€, (maybe) warning the reader against too easy appropriation of the stories of murdered soldiers:

“Can you pick out your favourite from the agents of malevolent damp?

Gather the troops from the flesh?

There are traps lurking in the mouldering pages, pockets of shock:

The flesh is scaryâ€

The poem seems protective of its protagonists, one of few that speak as a ‘we’; this aspect of denied individuality itself seems a point of existential pain, “O! Why are we still excited, why are we fused together, why are we good?†The ‘fair body’ of heroic death is offered, “the fulcrum / of our union, our own sad / undoingâ€:

“Take him and you will join us in our song.

But we are not responsible

for any injury incurred

in the violence of exchange.â€

One of the key texts for the collection is Orwell’s essay ‘Shooting an Elephant’, a memoir of his time as a minor imperial official in Burma in the 1930s. The piece is the site of deeply fraught relations between Orwell the colonial official and the local residents who he both resents and barely considers human (referring to the Burmese as “evil-spirited little beastsâ€, and, notably, to the elephant as a “great beastâ€). Despite this blatant condescension, Orwell claims that he too is ‘oppressed’, forced into “the conventionalized figure of a sahib†who must at all times feign power and wisdom; Orwell has the option of killing the elephant or (maybe) appearing indecisive, and so feels “in reality I was only an absurd puppet pushed to and fro by the will of those yellow faces behind.†What actual power the Burmese wield is unsubstantiated except in Orwell’s imagination, yet they bear the brunt of his anger and fear, manifested in racial slurs and spurious theories of reverse oppression.

Where the essay interacts with ‘Humpadori’, I think, is in its depiction of white assumptions of superiority when in contact with an unfamiliar culture. White critics like myself might be tempted to read ‘Humpadori’ through the lens of our experiences and presume that we have all the understanding we need to speak authoritatively about the collection. White readers, however, are not the book’s primary audience, and our lack of understanding is no failing in the collection; for all its acknowledgement of western iconography, ‘Humpadori’ probably speaks far more clearly to readers for whom Raj Kapoor, Asha Bhosle, Kali and Jà gannÄth are familiar cultural artefacts, more than occasions for education via google. What I can say is that it is refreshing to read a collection that asserts its non-anglocentric cultural perspectives as legitimate, and questions their suppression or characterisation as ‘monstrous’ or ‘beastly’. Though at first glance it may appear primarily ludic and carnivalesque, a performance of difference for the reader’s entertainment, it seems significant that in the penultimate interview sequence, the Interlocutor, who has painted Humpadori as a figure of fun throughout, loses his clearly defined sense of self, becomes one with the Other he had thus far kept at arm’s length:

“HUMPADORI: won’t you …

INTERLOCUTOR: will you …

HUMPADORI: won’t you … join …

INTERLOCUTOR: My leg is attaching to your spine, which is zipping out in space … and the Daisies … and Sentiments in their orgiastic tumbling … and the Shadies and Delicates in their orgiastic tumbling …â€

As daisies and sentiments become shadies and delicates, the lines between cultures and understandings of selfhood become deeply compromised. The closing poem, ‘HUMP Enters into the World Spectacle’, give the book’s hero/ine something of triumphant (triHUMPhant) send-off:

“HUMP creeps into the golden city          close close

dragging her gold rags                 her gold psyche              like a bride         our bride

HUMP creeps into the golden city            like gold pollution

We creep into the gold spectacle               and disappearâ€

Where Humpadori goes, the reader cannot. It’s a complicated gesture, and not one I’m confident of fully understanding. Perhaps it in this final ambiguity, a refusal to allow a grotesquely, gloriously multifaceted character to settle into a comfortable resolution, that the book’s strength lies; certainly there have been plenty of warnings throughout: “whose voice, you ask? I, for one, cannot tell whose lips are movingâ€; “You don’t know if I’m alive / or dead. Nobody has / your back. Anything could happen next. / You’ve never been safe here. Now: applaudâ€. The book progresses in tangents, asides and non-standard grammatical declarations; scouring it for a clear message is a more matter of fleeting, recurring impressions than linear, logical argument-construction. What seems clear is that Humpadori’s first declaration, “I’d say we’re pretty much all Humpadoriâ€, deserves far closer attention than it first pretends.