Ekushey Boi Mela, Dhaka

Â

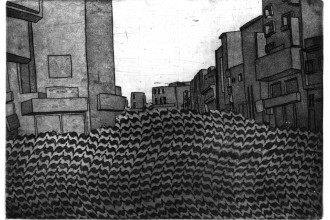

As night falls, we run across a crowded road, dodging cars, motorbikes, rickshaws, CNGs. At the roadside, someone taps my elbow twice and I look round to see a beggar, who stares at me cloudy-eyed and says, ‘Please, boss. Please.’ As I hesitate, a biker screams ‘Mamu! Mamu!’ (in this case, it means something like ‘Dude’) in my direction, and I move backwards just in time to avoid a sudden long-awaited surge in the traffic. I become simply another face in a crowd of thousands, moving along Shahid Minar Road past the University Campus, jostling for position every inch of the way.

I’m reminded of, years ago, elbowing my way through the crowd after a football match at The Millennium Stadium, holding my dad’s hand to make sure I reached our car safely. But this crowd in Dhaka haven’t been watching a football match (or even a cricket match) — all these thousands and thousands of people have spent their day looking at books.

The Ekushey Boi Mela (21st February Book Fair) is one of the big events in Dhaka’s cultural calendar. To a visitor from Britain, used to ‘literary festivals’ populated by amiable pensioners and teachers desperately trying to grasp the ‘meaning’ of a new poem on the GCSE syllabus, the popularity of the Boi Mela seems implausible and inexplicable, and a country where people will fight to get near a book stall seems an impossible fantasy.

And yet, to the people of Dhaka, books really do matter. Language matters. In 1947, the Central Pakistan Government, seeking to unite West and East Pakistan, decided that ‘Urdu and only Urdu’ was to be the official national language. The millions of Bengalis in the East were abruptly informed that their mother tongue would no longer be tolerated. Understandably, protests began, led by students at Dhaka University. On 21st February 1952, police opened fire on protestors and several students were killed. Today, everyone in Bangladesh seems to know the names of the ‘Language Martyrs’: Salam, Barkat, Rafiq, Jabbar… They are remembered everywhere you go.

Language, then, is bound up with national identity here in a way that it can never be in Britain. The national anthem, Amar Shonar Bangla, is adapted from a Rabindranath Tagore poem, and the poems of Kazi Nazrul Islam inspired protests against British rule in the 1920s. Is it too optimistic to see this as evidence that poems can intervene in the course of history?

It would be a mistake to suggest that everyone in Dhaka is passionate about reading. As in the West, films (both Hollywood and Bollywood) are the dominant form of culture, closely followed by pop music. It seems reasonable to suggest that many people are put off the idea of capital-L ‘Literature’ by antiquated school syllabuses which force them to study poems of little or no relevance. Reading the official textbooks used in Bangladeshi schools, it was hard not to conclude that they reinforced the idea that poetry must rhyme, must contain archaic vocabulary, and must always deal with the same narrow range of topics.

Despite looking at hundreds of Boi Mela stalls (often from a distance, due to the sheer size of the crowd), I failed to find a single book of English poetry, whereas books by (and on) writers such as Tagore and Nazrul sold thousands of copies. Of course, the Boi Mela is — particularly on the 21st — primarily a celebration of Bangla, but it was vaguely upsetting that the first English book I saw was Tony Blair’s autobiography: people from Dhaka could be forgiven for thinking that English writing hasn’t really moved on since the death of Shakespeare.

Minor quibbles about the under-representation of English writers aside, visiting the Ekushey Boi Mela was an incredible experience. While, back in Britain, the debate over the future of the printed book continues, it’s uplifting to know that here in Bangladesh thousands of people are celebrating the fact that books have the power to change lives.