Reviewed by Abbigail N. Rosewood

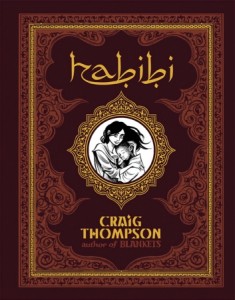

Craig Thompson, Habibi (Pantheon, 2011, 672 pages)

When I read Craig Thompson’s Blanket in high school, I appreciated it for its simplicity—from the clean drawings to the storyline about an introverted boy falling in love with a girl he thought was the feminine reflection of his taciturn nature, only to discover a reality that didn’t quite match up with his dreams. Blanket is an unfolding tale of adolescent love, which reveals its disappointment, a vague and yet potent sense of pain, and the consolation that we grow up, out, and away from it all.

When I read Craig Thompson’s Blanket in high school, I appreciated it for its simplicity—from the clean drawings to the storyline about an introverted boy falling in love with a girl he thought was the feminine reflection of his taciturn nature, only to discover a reality that didn’t quite match up with his dreams. Blanket is an unfolding tale of adolescent love, which reveals its disappointment, a vague and yet potent sense of pain, and the consolation that we grow up, out, and away from it all.

Thompson’s new graphic novel, Habibi, offers no such comfort. Refugee child slaves Dodola and Zam are, perhaps by both a curse and blessing, thrown together as children just long enough for them to feel the wretched despair of separation. Once again the author depicts adolescent love, this time in more dire and desperate circumstances.

Dodola’s life is intertwined with religious stories from the Qur’an, the first text she learned to read as a child. Dodola’s capture by the Monarch corresponds with Gabriel telling Jahannam that the people’s skin stretching  “revealing bowels full of writhing snakesâ€, was punishment for their greed. From starvation to decadence, the skeletal Dodola gorges on meat, wine, and pastries. Although similar religious parallels appear throughout the text, I did not once feel overwhelmed or bombarded by their presence. In fact, they only serve to demonstrate how closely yet incidentally Dodola’s life can be deciphered by both Islam and Christianity.

For many readers, the message is perhaps too propagandized to be tasteful—the notion that sex is completely eliminated from true love, that desire should be constantly suppressed and unfulfilled. Sexual activities are often depicted as violent, realized by force, or employed as a trade for food and other basic necessities. Despite all this, I still believe that Habibi is a story worth experiencing. After all, we cannot avoid that the world we live in functions by metaphors and that in our most desperate moments, we are empowered not by bread but by symbols. The clichéd, or more accurately rehashed, portrayal of the helplessness of Middle Eastern women against men is forgivable when it is this well done. As with many graphic novels, the pictures tell the story more readily than words. The long years it took Thompson are ultimately justified for the visual treat we are left with.

Abbigail N. Rosewood is currently interning as an editorial assistant at The Missing Slate. She describes herself as a vagabond at heart, a traveler and a couch potato, a library “frequenter,†a believer of God and an agnostic. Abbigail studies Creative Writing at Southern Oregon University and her work has appeared in a number of magazines, including “Blazevox”, “Pens on Fire”, “The Bad Version” and “Greenhills Literary Lantern”.Â