Highly commended in our Hallowe’en short story contest.

By Cynthia Green

Our new house was not new and not really ours since we were renting. What the small, dilapidated farmhouse lacked in elegance, it made up for in isolation. We could not see our neighbours and they could not see us. That was all we needed—privacy and a cosy place to hang our hats. The generic white clapboard sported crooked green shutters and a gable roof with a dormer window. Several acres of overgrown grass and clusters of untamed trees and bushes surrounded the dwelling. A small barn with good lighting was the perfect spot for Lisa to set up her canvases and paints. The farmhouse’s best feature was the long covered front porch with two wooden rocking chairs.

The property owner, who was almost as decrepit as the farmhouse, showed us around and quoted a ridiculously low rent. He spoke in grunts and single syllable words, never saying more than necessary. While Lisa was measuring the bedroom to make sure our new furniture would fit, I quizzed Mr. Findlay. Yes, he had moved there with his wife almost fifty years ago. No, the house was not for sale—too many memories. Yes, he would pay for paint, new faucets and light fixtures if we did the labour ourselves. Mr. Findlay wanted one month’s rent in advance. No need for a lease. We shook hands to seal the deal.

Our furniture was not due to arrive for ten days and Lisa and I celebrated one month of married life on the bare wood floor in front of a roaring fire in the living room. We dined on a bottle of domestic wine, cheese and crackers and slept in sleeping bags on top of an air mattress.

The sprucing up was more work than we anticipated, but we fell further in love with the place every time we painted a wall or hung a chandelier. At the end of each day, Lisa soaked her body in the cast iron clawfoot tub, while I shaved at the sink and watched through the mirror as she lathered soap over her slender limbs.

During the dog days of summer, I drove back and forth five miles east for supplies at the hardware store on Main Street. Mr. Findlay’s nephew owned the shop and no money ever crossed hands. Although he never said anything, old Mr. Findlay must have been happy with the changes we were making. He splurged for a pine island with ball feet I had admired at the hardware shop and young Mr. Findlay tossed in white ceramic door handles for the newly sanded and painted kitchen cupboards. We discovered pristine maple floors beneath faded linoleum tiles in the kitchen and, when we were finally finished, the house radiated warmth and charm.

The old place needed us as much as we needed it. We were not office minions but freelancers. Lisa painted children’s murals for hospitals and community centres and I wrote a sports column for several key newspapers across the country.

Our furniture arrived and we spent another few days arranging things until there were no more excuses. It was time for us to get back to work.

Each afternoon around five, Lisa cleaned her equipment and returned to the farmhouse. I would turn off the computer when I heard her calling from the hallway. Meals were prepared by Lisa. I wasn’t much of a cook, but she insisted I lend a hand and I was getting rather good at making salads and garlic toast. After eating, we relaxed on the porch and watched the sun glide down through the trees until dusk turned to night.

It was on such an evening while we were rocking on the porch chairs that we first saw them.

“Look over there, Johnnie.†Lisa pointed across the field towards a clump of red maple trees.

Two small silhouettes stood motionless. They were too far away to make out any details, but by their size, I determined the children to be under ten.

“I suppose they live down the lane,†I said.

Lisa got to her feet and leaned against the railing. “But it’s dark. Oh, the poor things must be lost. What should we do?â€

“I’ll call the police.†I went inside and the operator connected me, but an officer assured me there had been no missing children reported in the area.

A sense of dread swept over me when I stepped outside and joined Lisa who was returning from the yard. “I couldn’t find them, Johnnie.â€

“They’ve probably gone home. Come inside.†I took her arm, none to gently, and pushed her into the house before I bolted the door.

When Lisa returned to the house that afternoon, she admitted she had not been able to paint. We ate supper and washed the dishes before we went outside to sit on the porch.

Twilight was shimmering around us when we saw them again. They were closer to the house this time. One was a boy about ten and the girl a few years younger. In the purple haze, we saw their blonde curls and grey clothes.

Lisa got up and waved her hand, but the children remained motionless.

“Are they ghosts?†she asked.

“No, they’re solid.â€

Darkness swallowed the children and we came inside. I built a fire in the living room, but we couldn’t stop shivering and went to bed early.

I fell into a slump with my writing and Lisa couldn’t paint after she cut herself while chopping onions for spaghetti sauce. The gash wouldn’t stop bleeding and I rushed her to the nearest hospital where a doctor stitched the wound and gave her a prescription for an antibiotic cream.

While I was waiting in the pharmacy, I ran into old Mr. Findlay who was buying plasters for his corns.

“Hurts,†he said, pointing to his feet.

I nodded and wondered if that was why he limped. “Did you ever see a strange boy and a girl when you lived at the farm?†I asked.

He shook his head and I heard the phlegm in his mouth gurgle before he spoke. “Wife saw ‘em.â€

“But she’s been gone how long?â€

“Forty-five years.â€

“It can’t be the same children then.â€

The pharmacist gave me a wave to let me know the cream was ready. I smiled at Mr. Findlay. “You should have a doctor look at your corns.â€

*Â Â *Â Â *

Evenings turned cool and Lisa and I stopped sitting on the front porch. We decided to make a turkey with all the trimmings for Thanksgiving and invited Mr. Findlay to dinner. He arrived with a pot of purple mums for Lisa and he blushed when she kissed his wrinkled cheek. He ate more than his share of food and looked around the house with melancholy gazes.

“How long have you owned this place?†Lisa offered a bowl of mashed sweet potatoes to him and he scooped a heaping spoonful onto his plate.

“Wife and I came here after our honeymoon ‘bout fifty years ago.â€

That was the longest sentence he’d ever shared with us.

I smiled and reached for Lisa’s hand. “Just like us.â€

Findlay gnawed on his lower lip. “Gone.†He stared at his food.

“You mean she died?†Lisa asked.

Mr. Findlay looked up, his eyes moist. “Gone with the children.â€

I thought it heartbreaking that she had run off with their children and murmured my sympathy. The only sound was the munching and swallowing of food.

As soon as the sun began to set, I got up and switched on the new chandelier. Mr. Findlay struggled to his feet, thanked us and took his leave, right in the middle of Lisa’s peach cobbler. We turned on the porch lamp and watched him limp to his truck and drive down the long lane to the road.

Lisa was in the kitchen, stacking dirty dishes in the sink and I was lighting kindling in the living room fireplace when I heard a rap on the window.

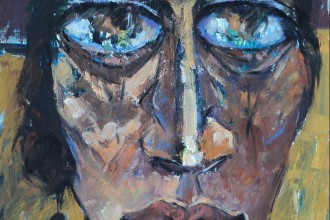

I turned and saw two pale faces staring at me through the glass. The children looked quite normal except for their black liquid eyes.

Rising from my squat in front of the hearth, I flung the door open and ran outside. They turned and faced me. The smell of rotting garbage filled the air.

“What do you want?â€

“We want inside,†the boy said.

“You must let us in,†the girl added.

I saw my own reflection in their black irises and knew they were not normal children.

“Go away.†As soon as the words were out of my mouth, I heard a pop just before the lamp above my head exploded. Glass flew everywhere. I covered my head, ducked, but jagged shards pierced my skin, and I yelped in pain.

I was alone when Lisa came running outside. She tended my wounds and I decided not to tell her what I had seen. There was no need to frighten her.

The next afternoon, I drove into town and went to the library, hoping to locate information about the farmhouse. Just as we’d thought, it was about a century old and had one owner before Mr. Findlay bought the place. Samuel Fletcher had built the farmhouse for his bride. There was no record of them having any children. She had run off, ten years later and one article hinted that he had gone mad.

I recognised the sound of gurgling phlegm and glanced up. Mr. Findlay was sitting near the magazine rack, reading a newspaper.

He looked surprised to see me. “Cost too much.†He pointed to the newspaper.

“They are expensive and we just toss them away the next day.â€

He gathered the messy paper sections so I could sit on the chair next to his.

I cleared my throat. “I hope you don’t mind my asking but I’m rather worried about—well about things.â€

“The house?â€

“No, not the house. Lisa and I love the house. We see children at dusk. I saw them looking in the window last night.â€

“Black-eyed children?â€

“Yes, with pasty complexions. How did you know?â€

His leathery hand touched mine. “Don’t let ‘em in.â€

“No, I didn’t. Who are they?â€

Mr. Findlay shrugged. “Only came at night.â€

“Why?â€

He shrugged again and stared out the window. “Came home and she was gone.â€

“Yes, you told us she took your children with her.â€

His eyes met mine. “Never had any.â€

A knot wrenched my stomach when I realised what he was saying. “Did she tell you about the black-eyed children?â€

“Said they wanted in. Needed a glass of water.â€

“Did she let them inside?â€

He shook his head. “Gave ‘em a glass of water on the porch. Kept insisting she let ‘em in the house.â€

“You think they took her?â€

“Came home one night. Door was open. Never saw her again.â€

I noticed the overhead lights spring to life and looked outside. Dusk was coming earlier and I must have forgotten the time. Lisa was alone at the farmhouse. I jumped up and fished in my pocket for my cell phone. The line rang until I heard my recorded voice. I hung up and ran out of the library.

The car sped through unlit country roads. The farmhouse lights were glaring through the windows when I drove up the lane and skidded to a stop on the gravel drive.

My hands gripped the wheel and my legs froze.

The farmhouse door was open.

Born in Toronto, Canada, freelance editor and writer Cynthia Green has published short stories in North America and Great Britain for the past twenty years. She has written a novel on Upper Canada’s illustrious beginnings called ‘The Memory Tree’.Â