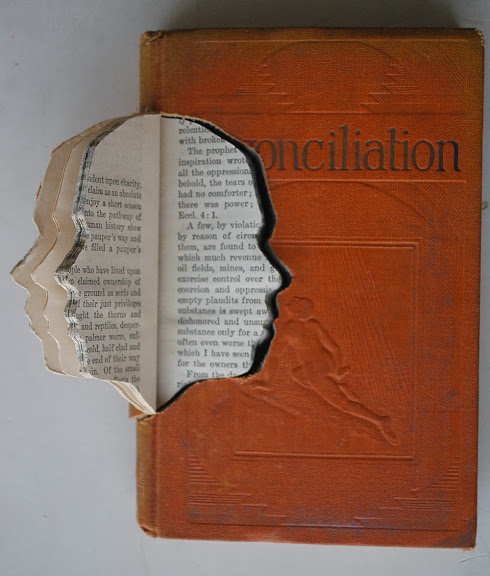

Artwork by Fraz Mateen. Image Courtesy ArtChowk Gallery

A writer and poet shares his experience at the third “Read my World” festival exploring Southeast Asian authors in Amsterdam

By Arturo Desimone

The third edition of the 2015 “Read my World” festival kicked off in October at Amsterdam’s Tolhuistuin cultural venue overlooking the port.

A fledgling world-literature festival, every year the directors of “Read my World” choose a new area of the world map as their theme, flying in poets from the chosen region. The organizers hope to unlock the political and literary intrigues of a faraway place for their audience in Amsterdam.

The first edition of the festival in 2013 showcased Arab literature — mostly poets from Palestine and Egypt — perhaps marking the first phases of an Arab depression, following the period of regional euphoria over the 2011 uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East. Poets as well as bloggers, activists and spoken word rappers were featured at the festival (as the pamphlets emphasise).

This year, Southeast Asia was the literary zone of choice. There seemed to be a focus on the Malay-speaking countries, with Indonesia (a former Dutch colony) at the forefront, as well as Malaysian and Singaporean authors. The presence of Indonesian writers at an Amsterdam literary festival shoulder-to-shoulder with second and third generation Indonesian-Dutch exiles and émigrés proved a very interesting, kinetic friction, both in the audiences and performers. For instance, some of the Indonesian immigrants resented the Indonesian nationalist revolution, while others had left their homeland because of the revolution’s betrayal. Questions of identity remain: for immigrants, memory becomes important in a way that is impossible to truly understand for people who have not immigrated. The immigrant keeps alive a period of history, with customs, memories and words that have become archaic and yet remain an existential necessity. (This may be the experience, for example, of the Surinamese of South Asian descent, who left India for South America in the early 20th century, and preserved musical tastes, traditions and Hindi words that became obsolete in India — part of the reliquary of stolen or lost generations. )

Marion Bloem, an Indo-Dutch novelist, gave a moving talk in memory of Tjalie (pronounced like “Charlie” ) Robinson. Bloem is the authoress of many novels such as ‘The Dogs of Slipi’ and the poem ‘No Requiem’, an homage to the Indonesian diaspora. Robinson was the first Indonesian-exile magazine publisher in the Netherlands to speak directly to the exile community with his magazine ‘Tong-Tong‘. He was also a radio disc-jockey and a singer-songwriter. He fought to create cultural platforms for what was then a new exile community still bearing the wounds of history. “Before Tjalie Robinson we could not find ourselves in the Dutch cultural world. Indos were depicted only as prostitutes or gamblers or wiseacres. Tjalie gave us other ways in which we could read about our society and our daily reality“. Bloem recounted how, as a young girl, every Tuesday returning from school her first priority was to find the latest issue of Tjalie Robinson’s magazine.

Bloem’s eulogy moved much of the audience. The writer, a funny and beautiful woman who is well-accustomed to giving public presentations, seemed overpowered by emotion in moments, recollecting a close relative — her Uncle Charlie.

The “Indos†(often known by the nickname “blue ones”, blauwe from the Dutch majority) were suddenly inhabiting a country that did not want to hear about them, even though many of them had served the Crown as mercenaries, earning their banishment. The Netherlands was rebuilding after the Second World War, aggrandizing its own traumas of the occupation and ”hunger-winter”, while Dutch bureaucracies were charging the tiny minority of surviving Jews for the years they had spent hidden in basements without paying taxes to the collaborating state. Holland was overwhelmingly a country of collaborators with the occupying forces during the Second World War. But there was in all likelihood far more trauma, and a silencing shame, within the Dutch establishment about the loss of their valued colonies. Indonesia was the jewel of the East India Company. Exile communities who came to the Netherlands expected a warm welcome, after having fought wars of guerilla counter-insurgency for the Orange Crown, but were instead seen as symbols of defeat and imperial insolvency. No community has excelled more in meeting with the pressures of assimilation than the Indo-Dutch. This makes them a very interesting exile society to put side-by-side with visiting intellectuals (most of the invited writers were academics who also write fiction) who descend from the people who stayed.

Lakshmi Pamuntjak, a visiting novelist from Java, presented a Dutch translation of her first novel ‘Amba: The Colour Red’ at the festival, as well as at other venues in Amsterdam. Pamuntjak‘s parents were exiles, persecuted by the anti-communist killing campaigns of the Suharto regime. Three million Indonesians presumably died in the ”disappearances” orchestrated by state-terror. ‘Amba’ is her personal story, as well as a commentary on the predicament of her generation and of the children of Indonesian militants, a broken generation. She is also a poet and essayist who wrote about the Homeric Iliad’s relevance in Indonesia. (The story of the Indonesian junta, and the burned generation of Lakshmi Pamuntjak’s parents, strikes a personal chord with me — because of my being a descendent of South American exiles from the state terror of the Argentine regimes, who fled to the tropical shelter of the Dutch Caribbean in the 1970s. The Argentine regime also conducted targeted disappearances during the 1970s in an attempt to annihilate ”subversive elements” within the young generation, claiming at least 30,000 lives.)

In Indonesia, the massacres of  three million suspected communists or “subversives†were followed by genocide in East Timor during which seven million Timorese islanders were systematically annihilated by Jakarta. Indonesian campaigns in West Papua are the most recent triumph of “Javanization” and ethnic cleansing by the Indonesian military, lasting into the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Also among the speakers was the eminent Dutch novelist Adriaan Van Dis (Dis also happens to be the name of the first city in Dante’s Inferno, but no matter). His most recent novel, ‘Ik Kom Terug’, or ‘I Shall Return’, is the story of his Indonesian mother who was exiled to the Netherlands, as well as ageing and nostalgia. Van Dis is one of the most polemically relevant authors in the Netherlands, despite the fact that he shies away from the activism that seems to drive the founders of “Read my World”.

Part of Dutch society seems to have entered a phase of post-imperial catharsis. The existence of the “Read my World” festival, and the often haphazard attempts at academic activism by its young organizers, attest to a process of imperial cultural catharsis involving the Dutch elites and intellectual classes.

Many Dutch-Indonesians — whites and of mixed-race — who served either the colonial government, or within the entourage of indigenous collaborators, faced exile after the Sukarno national revolution. The Netherlands waged counter-revolutionary campaigns that lasted throughout the 1950s and 60s, enlisting both Dutch soldiers as well as Ambonesian mercenaries (called molukkers in Dutch) in what led to one of the bloodier wars of decolonization in the twentieth century. Indonesia proved to be “the Dutch Vietnam” both in terms of its devastation, and in the defeat of the invader by indigenous resistance.

The Dutch trauma of anti-colonial war and counterrevolution is now, for the first time, being widely discussed in Dutch newspapers like the daily national ‘Trouw’, and even ‘Volkskrant’, which at times feature full-page photos of Dutch marines committing atrocities that were once denied, hidden behind the veil of a Dutch myth of ethische politiek (“ethical politics”, a term of newspeak or ”political correctness”) in the East Indies. Van Dis contributes articles regularly to the Dutch press that relate to societal discussions on the East India Company’s past. But the story of ‘I Shall Return’ is more personal, and concerns Van Dis’ relationships with his mother and sisters, and his fondness for Indonesia — despite his family’s being fairly right wing, and of conservative persuasion, anti-Sukarnoist like many of the exiles.

He talked about his nostalgia for his mother and of having overcome his Oedipal conflict — he illustrated this breakthrough by reading aloud a passage from ‘I Shall Return’ where he speaks of wanting to mount his mommy with caprice and enjoyment. To the likely displeasure of the victims of Suharto’s coup against Sukarno — many of whom were among the audience during this rare event of an Indonesian literary festival in Amsterdam — Van Dis also chanted anti-Sukarno propaganda songs from his Indonesian childhood, with much sentimental fondness. He later admitted that his mother, in later life, softened up politically and became proud of Indonesia’s independence declared on August 17th, 1945. The date of the Indonesian declaration of independence still goes without official recognition by the Netherlands, a negligence lamented by the writer.

Regardless of the ideologies preferred by the festival organizers, the politics of the right among Indo exiles is a relevant and interesting part of Indo diaspora society that needs to be confronted.

‘I Shall Return’ was published the previous year and won the Libris Prize, which was followed by Dis being awarded the Constantijn Huygens Prize in Dutch literature.

Van Dis represents the kind of literary phenomenon that in French literature finds a probable comparison (not to say companion) in Marguerite Duras, who left the colonial Indochine (French Vietnam) of her upbringing, herself a child of a settler mother and native father. Van Dis is far more interesting than Hella S. Haase, whose book for young readers, ‘Oeroeg’, about nostalgia for Dutch Indies colonialism, is taught to Aruban high school students (or was taught, when I was a schoolboy in Aruba).

An interesting dynamic erupted at the “Our Heroes” event. Particularly at the debate between Javanese writer Dyah Merta and Dutch TV-movie writer Gustaaf Peek (of part Indonesian descent). “Our Heroes” was organized by ‘Perdu’ editor Lisanne Snelders in the hopes of challenging how Dutch intelligentsia have praised Multatuli, as well as shaking the pedestal of Kartini, a famed Indonesian princess who wrote patriotic letters that were printed in Javan newspapers and magazines, examining the then colonial power and the role of women.

Merta read scintillating prose from her novel with an English translation that followed along on-screen. Lamentably, there wasn’t a live translation of her answers in the debate with Peek, who recently won a Golden Calf (Dutch cinema award) for a screenplay. Gustav Peek appeared to shine like a self-bedazzled apparition while delivering a sanctimonious speech denouncing Kartini, Multatuli and Indonesian political achievements as backwards and irrelevant. He accused Kartini of “scribbling away†while maidservants did “backbreaking work“. Peek, the awarded screenwriter, said all writers are ”scribblers”, unlike the people of Java (whose language he does not speak). Despite what Peek trumpets as the insignificance and pettiness of all literature (of which his knowledge is equally unflattering), he has no qualms inhabiting the gated corridors of premium art residencies, honours programmes and official platforms, his post being guarded from other ”scribblers”. Throughout his speech, Peek seemed to have carefully studied Leonardo DiCaprio’s address at the UN summit on Global Warming.

Merta laughed at Peek’s comment about his ”capuccino skin” and similarly superficial identity politics. As the only writer, and the only Indonesian on stage, Merta remained insistent that a Javanese person speaks Javanese, and internal knowledge of the culture and political dynamics are more important than his ”capuccino skin”, as he called it.

Merta had interesting revelations for the audience. She believes that Kartini may have been a pseudonym, or an invented persona, a ghost-writer with no Indonesian princess behind her. Despite the possibility of ghost-writing, Kartini was important to the consciousness of Indonesian women, more liberated and stronger today, having rights, access to higher education and a female president. Peek, to the contrary, seemed to harbour conventional notions about Indonesian women as defenseless and brutalized by polygamy. In his long shaming  j’accuse addressed to Kartini, he asserted the better example of his sister who, being raised and educated in the Netherlands, ”will strive to get ahead of the rest”, praising blind capitalist feminism.

Such are the identity politics of the mainstream in a nutshell: no mention of any geo-political consciousness about Indonesia, the genocides against East Timorese or the communists. No awareness of the great importance that art and culture have in the third world is preferable to the politicization of the Dutch celebrity’s ”capuccino skin’‘.

Multatuli was the first European author to challenge and deface the newspeak of Dutch imperial ethische politiek, (“ethical policy,†the propaganda of colonial benevolence, a political correctness of the 19th century.) Merta defended Multatuli as still bearing relevance to Indonesia, though his actual texts are no longer read in Indonesian schools. She hopes Multatuli’s vision might still have some resonance in present day Indonesia with its harsh capitalism and intolerance. But Indonesian revolutionaries of the past, and hopefully those to come, are inevitably more important in their destinies than Multatuli.

The cultuurstelsel, Â “cultural echelon”, the first phase of decolonization, created an awkward, colonially-ruled version of ”multicultural” ghettoes in Indonesia; it was a devastating period that followed the time of Multatuli. Dutch humanitarian elites certainly appropriated the classic as part of the traditional philanthropic defence of colonialism that remains in effect to today in the discourses on the Middle East, and on the Dutch Caribbean.

The main festival director Mathijs Ponte is a poignantly progressive opinion columnist freelancing in the ‘Volkskrant’ newspaper, and founder of the fledgling small press “Bananafish”, soon to publish much-needed Dutch translations of the St Lucian-Trinidadian author Derek Walcott.

The Absence of Aruba, Curaçao or St Martin at a Caribbean Literary Fest in Amsterdam

The third edition of “Read my World” is a follow-up to the second edition. The “Read my World†product seeks an arc or continuity in time, organised at the same place, with its directors who specialise in hiring out their curators in varying regions. The politics of first-world indebtedness to the third world is often at the forefront. Curiously, there is an incongruous gap between the second and third edition. The “Southeast Asian” festival emphasized the Dutch colonial heritage, whereas the previous edition did not feature the islands currently grouped under the Netherlands, except for a curator and artists from the mainland South American country Suriname, which had its anti-colonial revolution in 1975.

The Southeast Asian-themed collection of readings concerned mostly the Malay-speaking territories, with fascinating guests from Indonesia at the center.

It would have been equally interesting to learn about Vietnamese literature and lore; or to encounter more of the Thai poets who could have even added another layer of political depth, (Thailand recently became a junta military state, possibly comparable in its treatment of dissenting artists to Indonesia in the 1970s).

The previous year’s Caribbean edition of Read My World held in 2014, featured mostly very good programming with writers from the Francophone and Anglophone islands and the Guyanas. Haitian literature is a fascinating landscape, and it is important for Haitian authors to be present at a Caribbean festival. There was, however, a bizarre absence of any scholar, poet or lecturer from Aruba, Curaçao, Saba or St Martin, the islands that mostly still fall under the Dutch kingdom, despite Aruba and Curaçao having their own governments or even a figment of a nation-state.

“Read My World” explains its savvy formula on the website: they use local curators and experts to scout talent. Is a festival calling itself a Caribbean literary festival, active in Amsterdam, not creating a strange vacuity when it does not confront the existence of these islands?

The only Curaçaoan presence was cinematic: the excellent documentary by the Surinamese Cindy Kerseborn, Son of Curaçao (Yiu di Korsou) a film interviewing Frank Martinus Arion, the Curaçaoan poet, novelist and linguist extraordinaire, who died in September of 2015.

Kerseborn interviews and narrates in Dutch, as Surinamese do not speak Papiamento. Kerseborn is the maker of an interesting and varied series of documentaries featuring the poets of Suriname and of the island archipelago, of which Yiu di Korsou is the most well-known, because of the fame of Arion’s Dutch-language novels in the Netherlands. She has also interviewed poets such Edgar Cairo (Surinamese exile poet, journalist and performer who lived and wrote in the Netherlands), Michael Slory (from Suriname) and Roland Colastica (an actor and poet from Curaçao). She has championed the Surinamese novelist Astrid Roemer as well, one of the leading women of Dutch Caribbean literature.

There is no way that “Read My World’s” Surinamese curator, Sharda Ganga, an academic and theater-maker in Paramaribo, did not know of the existence of the islands or their having literature.

The Dutch organisers of the festival have a penchant for the kind of activistic trends that are predominant in academia in the United States and Europe: upholding the personal quests of young academics as being somehow expressions of revolutionary militancy: this is a tradition they have imitated from the United States, its academic world and its discourses through the University of Amsterdam. However, the tendency to insist that the worth of an artwork is in its capacity to serve as an illustration for the progressive opinions of the curators (or of the academic researchers) fits well within the liberal conventions of the Netherlands, requiring no such importation of American fashions.

Despite all the vanguardism, they excluded those islands presently or formerly under the colonial umbrella of the Netherlands.

There are Papiamento-language writers and scholars, many of them based partly in the Netherlands, who could have played a role in the festival had they been invited. These include the short-storyist Joe FortÃn of Aruba, (currently in enrolled in a Phd program in Leiden, not far from Amsterdam) or the Aruban linguist and Papiamento-historian Ramon Todd Dandaré. The St Martin poet and publisher Lasana Sekou was born in Aruba and writes verse in English. The Papiamento translator and poet Kaitano Sarah from Curaçao edits the electronic platform ‘Literatura na Papiamentu’ (‘Literature in Papiamentu’).

Having writers and scholars from Aruba, Curaçao, St Martin and the BES islands (Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba) would have made the festival more serious and consistent with its chosen theme.

This forgetfulness about the islands and their languages is nothing new in the Netherlands. The nostalgic curiosity the Dutch still have for Indonesia and Japan (the country that helped weaken the Dutch grip on its colonies) is always in stark contrast with the indifference towards the islands, which are seen as liabilities, philanthropic and unproductive projects, as superficial and over-compensated. The Netherlands has exported modern educational projects throughout the world, as far as the indigenous mountain villages of Bolivia, whereas on Aruba the school system still uses the colonial language, an archaic Dutch, undermining the Papiamento language spoken by Arubans. It is, of course, up to Arubans to wrest their education and schools back from colonialism. Post-colonial or intellectual consciousness seems relatively absent in the former Dutch archipelago compared to the rest of the Caribbean, where islands like Barbados, Trinidad, Martinique, Cuba and others have known a dynamic intellectual culture involving the islands’ youth.

Arturo Desimone‘s poetry and fiction have appeared in Hamilton Stone Review, New Orleans Review, Jewrotica, Small Axe Salon, The Missing Slate and the Acentos Review. He was born and raised on the island Aruba. At the age of 23 he emigrated to the Netherlands, and after seven years began to lead a nomadic lifestyle that brought him to live in such places as post-revolutionary Tunisia. He is currently based between Buenos Aires and the Netherlands.

[…] “Multatuli was the first European author to challenge and deface the newspeak of Dutch imperial ethische politiek, (“ethical policy,†the propaganda of colonial benevolence, a political correctness of the 19th century.) Merta defended Multatuli as still bearing relevance to Indonesia, though his actual texts are no longer read in Indonesian schools. She hopes Multatuli’s vision might still have some resonance in present day Indonesia with its harsh capitalism and intolerance. But Indonesian revolutionaries of the past, and hopefully those to come, are inevitably more important in their destinies than Multatuli.” By Arturo Desimone and here’s the link: http://journal.themissingslate.com/2015/12/10/read-my-third-world/2/ […]