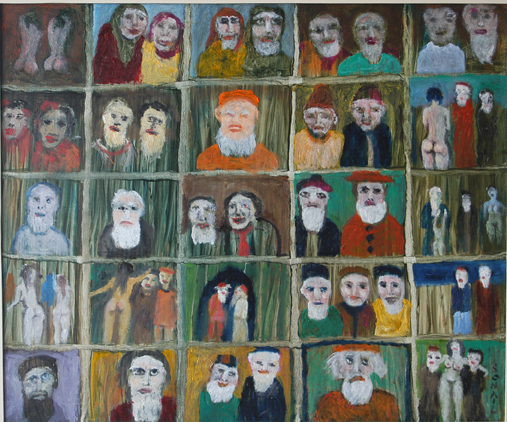

Strange World of Elderly People by Tassaduq Sohail. Image Courtesy ArtChowk Gallery

A strange meeting of minds in a senior centre

By Inna Viktorovna

“I go down there around Christmas to get my things,†Millie Holngren discloses, “but they are not there.â€

Around thirty other older adults participate in experimental interviews with novice college writers. Millie chose me because I sat at the edge of a white breakfast table, a prime location for parking her Envoy 480 Deluxe Rolling walker. She sits across from me at Augustana Care, senior housing in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in a red blazer, a flower-patterned undershirt, a set of matching pearl earrings and a necklace. She wanted to show me pictures of her family, letters and cards that have accumulated over her 98 years, and other memorabilia that every girl, lover and mother holds on to, to keep the most important memories alive. She insisted that they held the secret to bringing colour and flavour to her story.

When she first moved into the senior home a year ago, her grandsons took boxes full of accumulated family belongings down to the storage area in the basement. Furniture, apparel and food took priority during her migration from a single home into a senior paradise. Several months after she settled into her daily routine at senior housing, she decided to check up on her treasure boxes only to discover them missing.

“Who do you think took them?†I ask and lean in towards her. She assures me that theft played no role in it, because to say so would implicate Augustana, a Christian institution, in allowing sin to occur on its watch.

“I told the director, but he didn’t do anything about it. I’m sure it was only a mess up.†The room belonging to Millie originally housed an elderly woman from Kentucky. The Kentuckian hated Minnesota. Snow, cold, family — what could be worse? After a few days of feuding with her sister, the southerner (who from now on I’ll call “Maribelleâ€) bought a one-way ticket, paid men in navy uniforms to pack up her property and drive it back to where it belongs: Kentucky. Millie moved in while Maribelle’s possessions still occupied the storage area.

“It must have been a simple confusion,†she insists. Since only Maribelle knew which items belonged to her, and since she made no effort to inform the moving men, they must have accidentally grabbed the wrong items. Anyone could have made that mistake. Millie’s shoulders slump. “Moving costs a lot of money,†she explains. “The woman wouldn’t pay them to drive it back.â€

Millie glances past me; her lips quiver. All her memories, all her secrets lost, possibly trashed, in the heart of that warm state amidst mountains and conservatives. Even I wanted to believe in the plausible, heartfelt explanation for a horrific crime. I couldn’t imagine that another 98-year-old woman capriciously took Millie’s items just for the thrill of it.

“What else was I going to tell you?†Millie asks after informing me that in 1939 she and her husband moved to California where, “of course I started my own shop there, in California, in my home.â€

“How was life during the depression?†I interrupt. She gives me a blank stare. “The depression in the 30s. I’m really curious about it. Did you feel the effects?â€

“I cut hair from my house,†she replies and looks around the dining hall. To every inquiry, she either assures me that life has treated her well, really well, or declares, “If only I had my box of stuff, I could have shown it to you. There were all these memories, but I can’t recall them anymore.â€

But she does recall the basics: born and raised on a farm, taught in a one room school house, walked eight miles through rain and snow to her high school, attended a beauty school on 808 Nicollet Ave, married in 1939 to her boyfriend’s friend, worked for a year under a hair dresser’s supervision before opening up her own shop in California, and lived in a cabin on a trail before selling it after her husband’s unfortunate death due to smoking.

Still, her eyes glance at the carpet and the corners of her lips lower every time she reminds me that the memories she cherishes are decomposing in the foothills of Appalachia, but she also smiles because without tangible reminders “everything was so good.â€

“Would you relive anything?â€

“What was that?†She turns her ear towards me. I clear my throat.

“If you could relive your life, would you change anything?â€

“Oh no. My life was so good and so happy.â€

“Is there anything you regret?â€

“On no. My life was so good, so so good. I only wish your country and mine could be friends.†She is referring to the Ukrainian crisis and the sanctions that America has placed on my people, the Russians, “Why can’t the countries just be friends?â€

“Because men are in power. If only women ran countries, all would be well,†I point out. She doesn’t laugh.

“I just wish for all the countries to come together and all be Christian. Then we can all be happy,†she repeats for the eighth time. After 98 years consisting of two world wars, the Great Depression, Vietnam and the Korean War, the Red Scare, counter culture, the Civil Rights Movement, 9/11, the War on Terror, the housing bubble, and now ISIS, Millie still views the world as optimistically as my four-year-old niece. I wondered, could it be that losing her box of memories and photo albums actually created a happier history? Do the things we cherish and the materials we compile cause us more grief than joy?

No doubt the love letters and copies of our first airline tickets that we store away in our favourite perfume boxes bring us laughter and butterflies when we go through them years later. Scrolling my Facebook page all the way down to my first post reconnects me with the immature 15-year-old girl who exclaimed, “Kyrie!!!! i just cant stop thinking ‘bout her†and bickering with a certain Jacob Ames over who owned Kyrie. Whether they’re hard copies of our report cards, or electronic screenshots of an apologetic message coming from a loved one who never apologizes, these physical reminders remain the only material things that most people cling to, but do these reminders also save the pain when it is best to just forget? Of course, Millie might actually be a true optimist who, even with her boxes, viewed the world as a pristine place to live.

“But I forgive her,†Millie says, going back to the story of discovering her possessions missing, “I forgive her. Anyone could have made that mistake.â€

Inna Viktorovna is a Twin Cities native, she writes essays on a rooftop, hunts the archives and pretends she vacuumed the house when she hasn’t. Her writing has appeared in Wineskin, Harbinger Asylum, the Tule Review and the Cobalt Review. She won the “Best Essay on Convention Theme” Award at Sigma Tau Delta International Convention 2015.Â