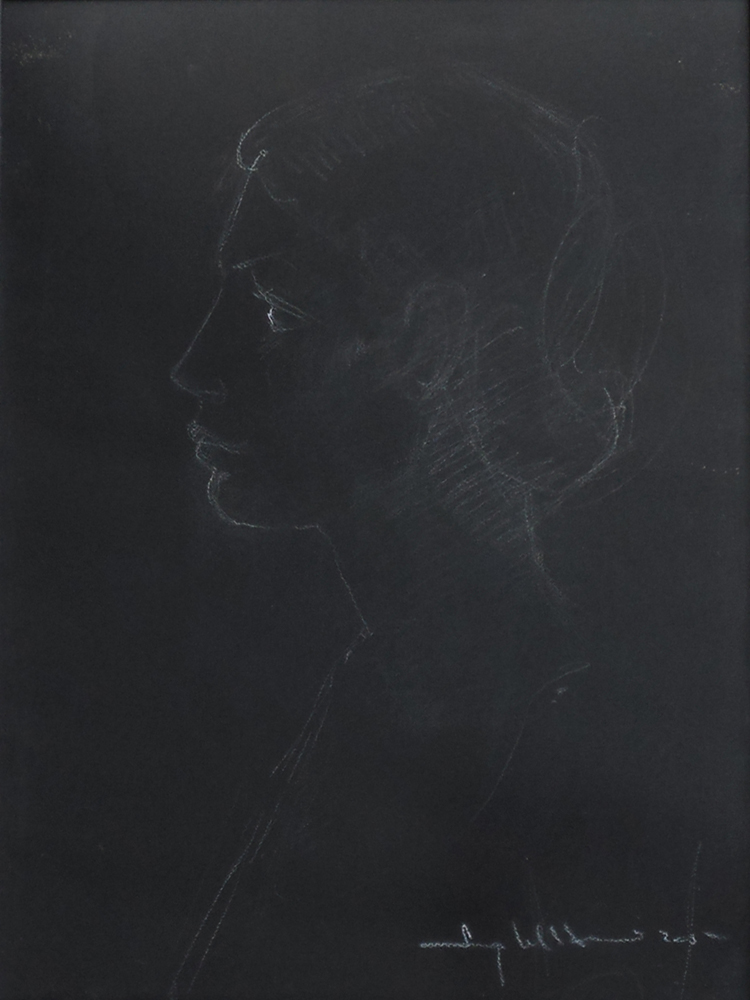

Artwork by Iqbal Hussain. Image courtesy of ArtChowk Gallery.

What the slutty city did to the Queen’s language

A few years back I visited Kulgacchia, a small town roughly fifty kilometres southwest of Calcutta. It’s probably the only place in all of West Bengal where the traditional ritual of the rice harvesting festival is turned into a major community event. I was there for one such festival.

It drew monstrous crowds. Women from neighbouring villages arrived with their entourage as if on a Chaucerian pilgrimage. Next to the giant cauliflower, club-size horse radishes and the shining irrigating tractor — beacons of the magical effects of technology in a still-largely agrarian society — were a series of tableaux featuring crude clay models, shrunk by twenty-five percent compared to average human dimensions on display.

Someone said, “Dyakh, dyakh, amaader scene?” (translation: ‘Oh look, isn’t that familiar?’). It was a reedy young woman with a huge child perched on her hip and two more huddled around her knee. She was trying to draw the attention of her friend, who I imagined was another harried mother and housewife like herself who took the rap from their abusive husbands as a matter of routine, assuming it came with the territory of having a man in charge of their lives.

The tradition of adapting English words as part of Bengali colloquial speech is at least two-hundred-years old. A maverick group of freethinkers who called themselves “Young Bengal” were probably the first generation of Bengali Anglophiles who started using English as the third-word default in common conversation. At any rate they were the most visible English users in 1830s Calcutta. Tutored in liberal western ideas at Hindu College (now Presidency University) by Henry Louis Vivian Derozio from 1826 to 1831, this precocious and radicalized set would throw English words at the conservative Hindu high priests to annoy and confuse them. Sometimes they went slightly overboard. Their attempts to liberate bigoted followers of Hindu rituals took the form of schoolboy pranks. For instance, they would throw alcohol and beef inside the courtyards of practising Hindus, who lived in perpetual fear of defiling themselves even if they were to inadvertently step on the shadows of these offending objects.[1]

If the provocateurs of Young Bengal were still around, they would probably be happy to see that the Bengali-speaking people have moved on to embrace a more inclusive and egalitarian culture since the mid-19th century. Words from the Queen’s language have been internalised by the working-class — mostly by unschooled women who commute to the city on a daily basis from the small towns of Bengal — popping up every now and then in the only language they speak. They speak a hybrid of an earthy, unrefined version of Bengali, sprinkled with Hindi and English words, which gradually and involuntarily seeped into their language from prolonged exposure to a metropolitan culture. Over the years, however, words borrowed from the English lexicon and made part of conversational Bengali have assumed a strange afterlife. Like an errant schoolboy, English words adapted as part of Bengali colloquial speech tend to go astray, moving away from its intended meaning in the parent language. For example, when the Kulgacchia housewife used ‘scene’, the word represented a reality that she experienced on a daily basis as opposed to someone who would say, “David Bowie is not my scene, I’m more into Amy Winehouse.”

Another rather hard-hitting use of ‘scene’ in Bengali vocabulary is by following a word with a negative, as in “Kono scene nei”, which means “no scene at all”, but the phrase can have a variety of meanings, such as “nothing doing”, “count me out of this” or “sorry, it’s not going to happen”. Similar to unpaired words, ruthless or dishevelled, for example — words in which the prefix or suffix seem to imply that taking them out and adding another with the opposite meaning might result in an antonym but doesn’t – the idea of “scene nei” too is defined by what it is not.

‘Border’ is a particularly loaded word in colloquial Bengali speech,  — a bit like “scene nei” in the sense that it is brought up, almost always, in the context of it being crossed, i.e. negating its existence. It’s only by defying, resisting or transgressing against the idea of a border that it becomes relevant. When a woman says, “aami kintu border cross-kora meye” (translation: “mind you, I’m a woman who crossed the border from Bangladesh to India”), she is using the act of crossing as if it were a weapon — as seen recently in the marvellously-evocative and disarmingly-realistic film Phoring, directed by Indranil Roychowdhury. It’s as if surviving the unmentionable hardships of illegal immigration made her tougher and more desperate, and also ruthless to a degree that a legitimate resident of India — unexposed to the possibility of rape, robbery, deceit and arrest, if not plain bloody murder, by the sentinels of territorial safekeeping along that crossing — could hardly ever match up to.

Those who crossed over from the east to the Indian half of divided Bengal during the first of the two major waves of mass migration (an estimated 3 million [2] in 1947 at the time of the Partition of India, and again over 8 million [3] at the time of the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971) would identify themselves as ‘refugees’ on a turf they had, technically, as much right to as the next Indian citizen. The new settlements they eventually moved into — typically rattan and bamboo structures erected on uncemented floors, with water hyacinths growing in the adjacent swamp drooping over the mud steps to the porch — were christened ‘colonies’. Someone who either grew up in a squatter colony in 1950s and 60s Calcutta, or relocated to it from a refugee camp, would be expected to have spunk and resilience to match her counterparts in East Harlem. At least that’s what the term ‘coloni’r meye’ (colony girl) implied. Displacement and the subsequent shocks experienced along the road to a new unknown had helped them shed some of the womanly inhibitions they were raised with. Now these women were after the jobs and eligible men that the nice girls who were born and brought up on the right side of the border had been groomed to acquire. An example is the go-getter Gita in Ritwik Ghatak’s film Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-capped Star, 1960) who goes on to steal her ever-supportive, self-sacrificing older sister Nita’s boyfriend. Although Nita herself was also an émigré, she hadn’t been as quick to adapt to the competitive temperament associated with a colony girl’s psyche.