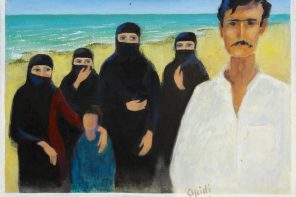

Artwork by Atif Khan and Damon Kowarsky. Image courtesy of ArtChowk Gallery.

Death in Vancouver is not cheap

2013

Where will Dad go?

Aunt Grace, the oldest of his eight siblings, forces me to take printouts of Craigslist ads in the hospital waiting room where we gather during my father’s final days, when we tire of wearing gloves and masks to see him in the ICU.

“It’s cheaper if you do it privately,†she says. Later, she finds the name of a funeral services agent who will give us a discount. “But you have to sign with her now,†she insists.

It’s only when I look at the prices on the printouts, and speak to other agents, that I appreciate the sense in her thriftiness. Land’s not cheap in Vancouver. Neighbourhoods have been remade: older, physically sound houses torn down to be built over with grander ones; others that (supposedly) sit empty as investments, and not as homes, by overseas investors. The cost of living doesn’t go down by dying.

It’s those who entered the market early who seem smart. Like my poh-poh, my mom’s mom. She prepaid for her plot in 1980 for $200; it’s now worth fifty times that amount. That’s a better return than residential real estate or the stock market.

One night Dad, in a fit of delirium, suggests that he’s signed away the house to loan sharks. It’s a fiction, concocted from some other recessed guilt; Dad’s eyes glisten with remorse. He spends the next day tapping at his iPhone with his thumbs. He’s trying to place that last call — as if he could call someone to make things better — even with the tube in his throat.

We all wish we could find those final essential words, but instead we fill the space around them.

1888

Surrounded by water is the tip of a piece of land shaped like a seahorse. In the evenings, a harbour master lights a stick of dynamite so that the fishermen on Vancouver Harbour can set their watches. One day, a team of men hack away at a pile of dirt. They’re building a road on the peninsula’s perimeter.

The road will circle the park, a tourist destination for the newly built rail line terminus. It will link and add to Aboriginal trails and old logging paths built under the moist shadow of fir, spruce, and cedar trees. Surveyors are instructed to literally cut through the existing homes by the water. Families are startled during breakfast as workers draw lines through their homes. The city will eventually compensate them with $50 payments.

Today, the surveyor’s path will lead a team of CPR[1] axemen through one of the midden piles that dot the settlement. As they dig through the mound, they find a trove of clamshells. And then something else.

They gasp, their faces wretched with dismay.

The land has long served as a resting place for the dead of the Squamish nation and then, in the last half of the nineteenth century, for non-aboriginal settlers.

“Indians always bury close to the shore, but the Chinamans are further from the shore,†August Jack Khatsalano will recount. His own father, Supple Jack, was buried nearby after he was kicked by one of his cattle. “I see Chinamans burnings stuff there once — for to feed the dead. The white mans are buried all along that shore too.â€Â [2]

The workers carting away the midden materials return the bones they recover to the aboriginals; the clamshells are used to pave the roads and give them a pleasing white colour.

Later, visitors will park their cars at Brockton Point, and think of the men who raced on bikes with wheels as big as dinner tables and admire the lighthouse. Few will know they walk above human remains. They will think of Stanley Park as the one piece of the city that has not been built over, and not another site that has been remade, forcibly forgotten.

2013

My brother, Dan, can’t make small talk, can’t separate imminent family grief from a sunny stroll through a graveyard. I manage to keep up with the bantering cemetery director, in his tie and fleece, who guides our family from the office to a nearby pathway that leads to the fountain.

“You’re the older one?†he asks me. “I can tell.â€

Cemeteries keep company with cities like trails of smoke. Mountain View Cemetery opened in 1887, a year after Vancouver incorporated. Its first resident, who died that February, was an infant named Caradoc Evans. Like an actual city, the public cemetery is made up of twelve neighbourhoods, including the areas where the Chinese (including my great-grandfather) and Jews were once buried. My father will be buried in the Masons area.

“It’s closed,†Aunt Grace told me when I suggested we buy my father’s space here. It’s true that a year before the city’s centennial, Mountain View had run out of space. But unused plots were reclaimed, pathway spaces and newly constructed columbaria —  house-like structures made of stone — were used for cremated remains. People now favour burning; they want to take up less room when they die.

Back in the office, Aunt Grace nods in approval at the city-subsidised price and my mother brings out her chequebook.

Dad has a few more days left. He’s prepared us, in a way, for his passing with his repeated hospitalisations in the past decade. In one of his first stays, he told me who to call about his insurance policy. A few days ago, he gave my brother and me Chinese names for the kids we plan to have.

But I won’t be ready, a week later, to enter his house with his framed portrait in my arms as a hearse idles outside. This will need to be done because Dad died at the hospital, and his spirit is unsettled. My mother will tell me what to say (as per Chinese tradition): “Welcome home. Come back anytime.â€

1973

A poet named Leung Ping-Kwan accompanies his friend to Chai Wan in Hong Kong. They’re visiting his friend’s father, who died in March. It’s a damp spring day as they ascend the graveyard. The dead are buried in terraced sections on the hillside, like an auditorium, with guard rails between levels. A chill has sunk into the dimming air.

They step over puddles and errant planks set aside by graveside workers until they reach the new, unmarked grave. His body will only rest in this site for six years, to save space in this densely packed city, before his remains are disinterred for cremation. The poet’s friend places the flowers on the grave and they bow three times in respect.

The poet and his friend continue onto the adjacent soldiers’ cemetery, where the white tombstones sit in orderly rows, looking down at the smog-smocked skyscrapers in the far distance. Alone together, they notice the chirping birds and flora.

A year after the poet dies of cancer, only a week after Dad’s death, his son will visit Vancouver from his place in Toronto. He’s in town to check in on the family home in Vancouver, which has sat unoccupied since his father fell ill; there’s an offer on the table from a developer. The rest of his family is in Hong Kong. He will give me a collection of his father’s poems, which includes the visit to Chai Wan.

“We watch the neatly spaced plants growing wildly,†the poet writes, “the red petals that bloom in the morning and wither at night.â€Â [3]

Remembering the dead, renewed by the world. And in his words: another promise of life.

2015

My pregnant wife, our son, and I walk twenty blocks, past unopened storefronts and then sleepy residential areas on a clear winter morning. Mom and Dan come by car. It is New Year’s Day, the first anniversary of Dad’s death. We bow three times in front of the grave, before Mom cleans her husband’s grave and then sets the aluminum baking tray in front of his grave marker.

I squat down, then fumble with the lighter. Mom tells me to burn the paper money first. The corner of the bills, to feed her husband in the other world, blacken and then shrivel in flame. We light incense sticks and use them on a cardboard Mercedes.

It’s the paper house, for Dad to live on as a spirit, that’s slowest to catch fire. When it finally does, I step back in surprise. A flame reaches from inside and drags down the house.

Into smoke goes our observance, a home in the heavens; all that remains is ash.

[1] Canadian Pacific Railway

[2] Jean Barman, Stanley Park’s Secret (Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing), 95.

[3] Leung Ping Kwan, “At Chai Wan Cemetery on May 28—for Hudson.†Leung Ping Kwan, Leung Ping Kwan (1949-2013), A Retrospective (Hong Kong: Leisure and Cultural Services Department), 160.

Kevin Chong was born in Hong Kong and raised in Vancouver. He’s the author of five books of fiction and non-fiction. As a journalist, his work has appeared in a range of publications, including Taddle Creek, Chatelaine, Maclean’s, Maisonneuve, Vancouver Magazine, and The Walrus. He teaches creative writing at the University of British Columbia and SFU’s The Writer’s Studio, co-edits Joyland Magazine.