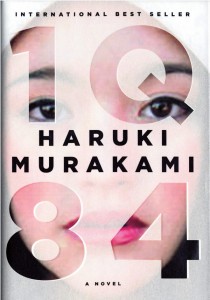

Haruki Murakami, 1Q84, trans. Jay Rubin and Philip Gabriel (Knopf, 2011, 944 pages)

In my first year of college, I was introduced to Murakami. Not much of a sci-fi or fantasy reader, I found magical realism to be the perfect alloy between literary fiction and fantasy. I was enveloped in Murakami’s universe of talking cats and fish rain, where magic doesn’t necessarily remove us from our world or provide us with an escape, but grounds us still more to reality and shows us that even under a sky of raining fish, we continue to long for love and seek for that mysterious something that gives us meaning.

Holding 1Q84 in my hand, I had high expectations. The hardback cover was impressive to hold. The filmy sleeve masked the faces of the two main characters on the front and back of the book, characteristic of the dream-like world in Murakami’s work.

The story follows Aomame and Tengo, whose lives are so profoundly different, yet eventually converges when they are thrust by a mysterious force into the parallel world of 1984–1Q84. The chapters alternate between Aomame and Tengo’s points of view. Each chapter is short and quick-paced and the ending always leaves me with a question and propels me to turn the page. This is also the reason, I believe, for part one being the most successful of the three parts. A hundred questions spring up as the reader encounters the religious cult which people disappear into never to be seen again, the sudden appearance of a story written by a dyslexic teenage girl that disrupts and bewilders the literary community, the shelter for abused women that goes further to protect them than expected.

The build-up is perhaps so ambitious that any attempt at resolution inevitably falls short: my questions were not adequately answered but merely touched upon as a side note. For example, until the end of the book there is still no justification for the existence of the Little People and what their roles were in 1Q84. In part two and three, the fantastical qualities almost disappear altogether, to be replaced by a heavy religious undertone. In reading the first part, I withheld judgment regarding the lurid descriptions of the consequences of rape on a child’s body; I find the explanations at best unconvincing and at worst frightening. Many of us have read Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita and sympathized with his passion for the elusive Dolores Haze. In the same note, sexual relationships with young girls in 1Q84 are explained by passionate love. The difference is that love is not directed towards these girls. They are used as mere vessels for the real lovers of the story. Through a young girl, someone else is impregnated without any sexual intercourse. By now the parallel with the virgin birth of Jesus Christ is almost undeniable. It wouldn’t bother me so much if the love story wasn’t raised up as pure and admirable. Our corruption as humans is understandable because it makes us just that–humans. Still, it is one thing to acknowledge fault and another to glorify it.

Despite the disconnected plot and lack of answers, there are still many good things I can say about 1Q84. At times it reads like poetry and the beautiful images lodged themselves inside my mind and carried me through a tough day. Unlike many contemporary writers, Murakami is willing to break boundaries and challenge what we accept as real and ordinary. Although 1Q84 may not always compare favourably with his earlier work, I can’t help but be thankful for the few moments when my imagination is ignited by Murakami’s words. Those who have been in love know that very few instances in our relationships actually make it into our poetic memory–the part that moves and inspires us to keep going when it gets hard. Reading Murakami is, in a way, like falling in love. Not all of it is good, but when it is, it proves worth the long journey.

Abbi Nguyen is currently interning as an editorial assistant at The Missing Slate. She describes herself as a vagabond at heart, a traveler and a couch potato, a library “frequenter,†a believer in God and an agnostic. Abbi studies Creative Writing at Southern Oregon University and her work has appeared in a number of magazines, including Blazevox, Pens on Fire, The Bad Version and Greenhills Literary Lantern.Â