From Leonard Cohen to literary translations, a hip hop artist to a Hollywood musical, a bildungsroman to the passing of a great art critic, The Missing Slate’s 2016 picks reflect a year of diversity and nostalgia.Â

La La Land, directed by Damien Chazelle

Maryam Piracha, editor-in-chief Â

We went into the theater with some trepidation. But from the moment it started, with a song and dance number, my doldrums were gone. La La Land is the film to see for 2016: it’s the light at the end of a very long, very tortuous, very prejudiced tunnel.

It features an electrifying performance from Emma Stone — it’s her little, subtle expressions that bring the characters she plays depth and a sense of imminent heartbreak. She’s wonderful.

La La Land will transport you somewhere else; where depends on your frame of mind before, during, and after the film. But you’ll be happier that you saw it.

Close Second: Actor-in-Law, the first Pakistani film I saw this year, and another that lived up to the hype. I’m not sure of its international (and likely subtitled) distribution, but this is a gem of a film. For starters, it takes up issues that are especially relevant in today’s Pakistan: the objectification and sexualisation of women; the country’s constant electric power outages; and not to be forgotten, the power of politicians over journalists willing to be bought; with side stories of the honesty and scruples of our heroes. It’s a ray of light in what’s been a bleak year for the country. That the story was scripted by a woman is just icing on the cake.

I’m bowing out of the best book pick of 2016 this year; most of my reading turned out to be books that were published as their ebook version (or reprints for Pakistan) this year, but were originally published in 2015. Woe is me. While I did read books published squarely in 2016, I defer to my excellent, well-read colleagues for their picks for this year’s best in publishing.

‘Sadequain and the Culture of Enlightenment’, by Akbar Naqvi

Haseeb Ali Chishti, Art Editor

I’d like to think I would’ve chosen ‘Sadequain and the Culture of Enlightenment’ as my favourite book of the year even if its author, Akbar Naqvi, hadn’t passed away last month at the ripe old age of 85. One of the most eminent art critics and historians on the subcontinent, Naqvi published ‘Sadequain’ early in 2016, a testament to his longevity. Though he is gone now, one hopes that his collection of essays and articles will be compiled and published to serve as a beacon for future academics and researchers hoping to serve art.

Naqvi doesn’t just limit the book to a discussion of Sadequain, Pakistan’s most iconic artist. Rather, the tome is an attempt to understand the cultural and historic milieu that shaped his work. The volume focuses on Sadequain’s contribution to calligraphy, his connection with his contemporaries, such as Chughtai and Shakir Ali, and his poetry, but there are also frequent and illuminating digressions on the poetry of Iqbal, the philosophy of Rumi, Amir Khusru’s music and a whole plethora of luminaries that paved the way for Sadequain.

Naqvi attempts to trace the culture of Pakistan back to its roots. He reclaims Sadequain as an original surrealist from those who claim the artist ‘easternised’ surrealism after learning about it in Paris. He does this through insightful discussions on Sadequain influences such as ancient Indian mythology, Arabic, Persian, and Urdu literature, as well as the Muslim Enlightenment during the days of the British. Sadequain is undoubtedly the greatest Pakistani artist of the last century, but such is our national pride in the arts that out of the 14 books published by the Sadequain Foundation in the US, only three have seen the light of day in Pakistan. In this barren wasteland, we remain to mourn not just the dream of enlightenment, but the passing of voices such as Akbar Naqvi who spent their lives awakening us to our own past.

‘Stories About Tacit’, by Cecil Bødker

Translated from the Danish by Michael Goldman

Casey Harding, Managing Editor

In ‘Stories About Tacit’, Cecil Bødker creates a world in the vein of Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. While not nearly as vast, the characters and setting of this story collection have just the same power. This comparison is aided by Bødker’s incredible command of language. Certain passages rang with such force that I found myself re-reading the same page aloud until it was near memorized.

In ‘Stories About Tacit’ you follow Tacit on his gradual growth into adulthood. Throughout the book, aided by the expert translation by Michael Goldman, I was struck again and again by the sheer humanness in the stories. The characters Bødker created live and breathe in this world: whether it is Tacit cutting off the fringes of his Grandmother’s bedspread to make it look more like a boy, to Tacit coercing a female friend of his to go swimming and then comparing her to a fairy tale that he invents on the spot, to Ælgar, an old man who the town is convinced committed a murder years ago and who just wants to be left alone with his horse, these stories are filled with the minutia and beauty of real life. As with Faulkner, authors like Cecil Bødker only appear once, and to miss one is to miss a glimpse into the humanness that connects us all.

*An excerpt from ‘Stories About Tacit’ appeared in The Missing Slate on March 3rd 2016.

‘Freetown Sound’, by Blood Orange

Pratyusha Prakash, Social Media and Poetry Editor

‘Freetown Sound’ is simultaneously an ode to black culture and a discussion of the perils of being black. The nature of conveying an identity is fraught with pitfalls, and the lyrics explicitly outline the struggles of a black man confronting racial and sexual issues. As Dev Hynes, aka “Blood Orangeâ€, himself says, “My album is for everyone told they’re not black enough, too black, too queer, not queer the right way… it’s a clapback.” He chooses to address these issues through what is essentially a collage, with multiple vocals, spoken word, and sound bites. These add to ‘Freetown Sound’s’ multifaceted narrative.

Female artists shine in this album. There are more familiar names (Nelly Furtado, Carly Rae Jepsen) alongside relatively unfamiliar ones (Kelsey Lou). They round off the album, give it depth and texture. They carve out their spaces, adding to the album’s shifting perspectives and pluralism.

Although ‘Freetown Sound’ can certainly stand on its own, it speaks to the zeitgeist of the age. There are several overt references to current events, perhaps most strongly in “Hands Up”, which references the 2012 murder of Trayvon Martin. Elegiac tones are overt, especially in the instance of “Cry and burst my deafness/ While Trayvon falls asleep” (Augustine).  In “Chance” Hynes sings, “All I wanted was a chance for myself.” It’s peculiarly haunting, a sentiment that underlines the anxieties of being black in America: overlooked, forgotten, ignored, misunderstood, and in perpetual danger.

‘The Good Immigrant’, edited by Nikesh Shukla

Alexander Gingell, Nonfiction Editor

“It was as if, even though we had been born here, we were still seen as guests, our social acceptance only conditional upon our very best behaviour.â€

‘The Good Immigrant’ is a collection of twenty-one essays by black, Asian and minority ethnic voices, crowdfunded in a matter of days, and documenting “what it means to be a person of colour†in Britain today. From actors, journalists and academics to poets and comedians, the contributors explore, among myriad other subjects, the reasons why immigrants come to the United Kingdom, why they choose to stay or leave and what it means to be “other†in a country that all too often “doesn’t seem to want you, doesn’t truly accept you — however many generations you’ve been here — but still needs you for its diversity monitoring forms.â€

A central tenet of ‘The Good Immigrant’ is its confrontation and exploration of the suggestion that immigrants are welcome in Britain, but only under certain conditions. Editor Nikesh Shukla was inspired, at least in part, by discourse surrounding why society seems to view people of colour as “bad immigrants†— “benefit scroungersâ€, “job stealers†and potential threats — until, by certain means, such as becoming an Olympic gold medallist, “baking good cakes†or “being conscientious doctors,â€Â they cross the divide and become “good immigrants.â€

Particularly powerful for me were Wei Ming Kam’s ‘Beyond ”Good” Immigrants’, in which she looks at the ‘model minority stereotype’ and the lack of East Asian representation in politics and popular culture, Riz Ahmed’s evocation of repeatedly being searched and detained in airport security in his ‘Airports and Auditions’ and Musa Okwonga’s ‘The Ungrateful Country’, which asks why the media coverage of the immigration discourse has largely failed to recognise what countless immigrants have brought to Britain, both culturally and economically.

The voices in this collection are disparate and different, and they reach various conclusions, yet they are united by a collective acknowledgement of the urgent need to ask certain questions. Humour, anger, optimism and despair rub shoulders in this poignant, thought-provoking and immensely important collection.

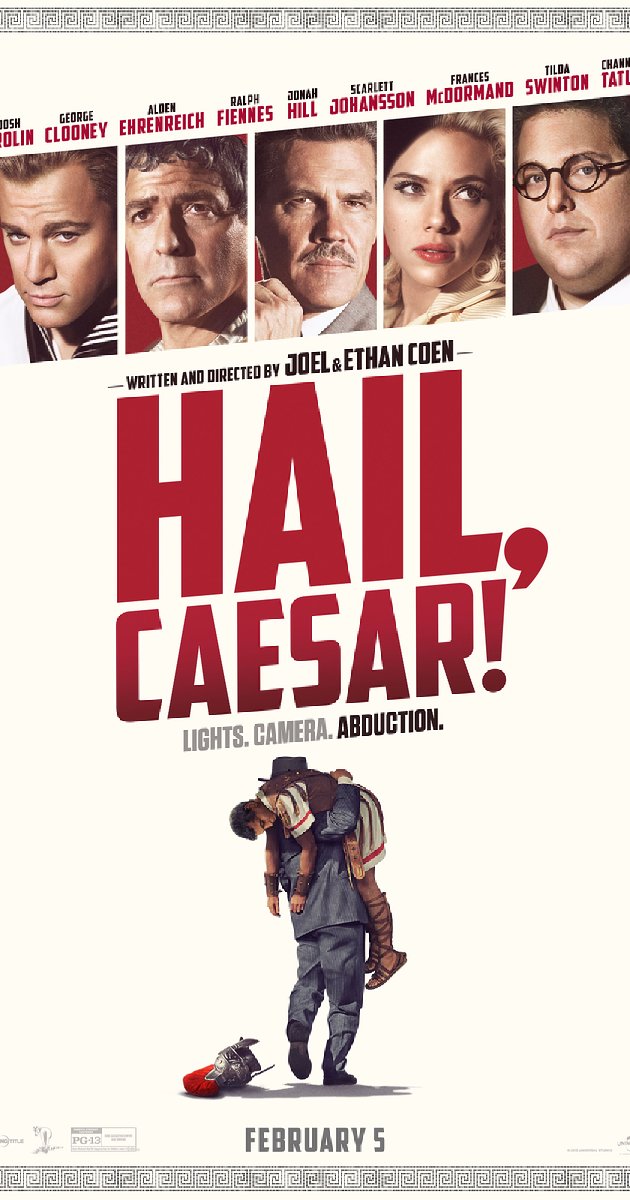

Hail, Caesar!, Directed by Ethan and Joel Coen

Aaron Grierson, Contributing Editor

This film, as much as it is touted as a comedy, is a great deal of other things: a historiographic tour; a social commentary; a satire of Hollywood rising. Much of it can only be appreciated with some targeted reading prior to watching, or an established love of historical Hollywood.

While I understood the reference categorically and stylistically in Channing Tatum’s homoerotic dance number as a shore-laden sailor, I couldn’t have told you what films it was referencing. The same goes for the most obvious, or at least most central reference. Film savvy people have informed me, that Clooney’s character is alluding to the recently (and probably dismally) remade Ben-Hur.

Many critics shot at the lack of plot, especially around the communists, something I would argue is intentional. Regardless, it’s still a sharp, often satirical look at the time. It depicts many the card carriers as what they are, generally harmless idealists who just want some recognition for their hard work. An idea which in and of itself is rather un-communist.

Everyone, every cliché, and every trope is picked on equally in this movie. The characters are walking archetypes, and with one exception, are the opposite of their in-film actor/ess counterparts. If you appreciate the history of film, or Hollywood, or the Coen Brothers, then I would heartily recommend this film, even if you don’t do your homework.

‘Some Rain Must Fall’, by Karl Ove Knausgård

Original title: ‘Min Kamp 5’ (translated from Norwegian by Don Bartlett)

Jacob Silkstone, Managing Editor

Is Karl Ove Knausgård’s ‘Min Kamp’ series beginning to outstay its welcome? The comparisons to Proust (European writers with multi-volume semi-autobiographical ‘novels’ and surnames that the uninitiated tend to stumble over) are less frequent now, giving way to suggestions that Knausgård’s writing somehow encapsulates white male pretensions and privilege. For all the initial acclamation, not many people bought the first volume, fewer managed to finish it, and hardly anyone has read the entire sequence (the sixth and final volume is currently being translated into English).

‘Some Rain Must Fall’, the English title of Don Bartlett’s latest Knausgård translation, contains the fifth and sixth parts of ‘Min Kamp’ (echoes of Hitler completely intentional). Knausgård’s fourteen years in Bergen are spread out over roughly 650 pages. At first glance, ‘Some Rain Must Fall’ is a fairly traditional bildungsroman: the young, rather naïve protagonist arrives in the city (if you can stretch your imagination far enough to call Bergen a city) for the first time and attempts to make his way as a writer. After several initial setbacks (for the young writer, nothing is truly a failure if it can be remoulded into a decent anecdote), the story ends with the protagonist’s debut publication(s) and some sense of forward motion.

So far, so conventional. And yet ‘Some Rain Must Fall’ offers, at its best, a sense of something stirring far beneath the surface of the text. “What was consciousness,†Knausgård asks in one passage, “other than the cone of light from a torch in the middle of a dark forest?†The darkness around the edges of the text presses closer at certain points, particularly in episodes connected to Knausgård’s drinking (for the second time in the series, Knausgård —uncontrollably inebriated—slashes his face with a fragment of glass; the parallels with his father’s self-destructive alcoholism are hard to avoid).

Don Bartlett’s English translation is consistently impressive, but not quite flawless. He mangles the name of Bergen’s largest mountain (which appears first as ‘Mount Ulrich’ and then, correctly, as ‘Ulriken’) and omits sections of the Norwegian original: a lyric entitled ‘Hun, Hunden, Hun’ has either been written off as irrelevant or written off as untranslatable. Minor gripes aside, Bartlett’s achievement is as worthy of admiration as Knausgård’s: ‘Some Rain Must Fall’ is, at the very least, a strong contender for 2016’s best translation.

‘Guapa’, by Saleem Haddad

Elishma Noel Khokhar, Nonfiction Editor

My motivations for reading Guapa were simple: it is the narrative of a non-western, LGBTQ protagonist, a young gay Muslim Arab man — Rasa — set against the backdrop of a failed political upheaval.

The reader is skillfully roped into the fast-paced narrative, interwoven with Rasa’s double consciousness of performing everyday heterosexuality and leading a closeted existence. Rasa explores his inner conflict and sense of duty towards Teta through the concept of eib (shame): “The closest word for eib in English is perhaps ‘shame’. But eib is so much more than that. The implication of eib is kalam-il-nas, what will people say, and so the word carries an element of conscientiousness, a politeness brought about by a perceived sense of communal obligationâ€. Shame is a moral and social code that pre-ordains existence and therefore, the identity of a child before they even enter the world. It creates painful fissures for those on the margins leading lives in liminality.

Guapa’s literary weakness lies in the unnamed Arab country that the novel is situated in. In a recent interview, Haddad explains that this was a deliberate move to promote “inclusive solidarityâ€Â as opposed to dominant pan-Arabism. But it leaves his characters wanting. Where is Rasa from? How does Rasa contextualise his politics? Is his nationalism country specific? These questions remain unanswered.

‘Guardians of the Zone’, by TupperWare Remix PartyÂ

Aaron Grierson, Contributing Editor

Tupperware Remix Party is a band hailing from Halifax, Nova Scotia (formerly of outer space) and they bring the 80s home in the hardest way. Did I mention that these guys wear costumes that they’ve never been seen without? They’re robo-aliens infecting Earth with positivity.

Probably best described as a funky electro-rock band, they seamlessly blend genres together with sweet sythns, mad bass and guitar solos, as well as the occasional keytar toss. ‘GotZ ‘ is TWRP’s fourth official album, with their third released in January 2015 and another EP due for release in a couple of months, they show no signs of slowing down.

The album itself is something of a more eclectic mix – some of the first songs have almost more of a chamber pop feel with the inclusion of organs, but the latter half brings out their true form. “Groove Crusaders” is perhaps the most quintessential song of the album, because it sounds like it could be the theme song for a cartoon from the 80’s. Every song, in its own way, is ripe with positivity and always upbeat, even when offering “Business Tips” for the aspiring employee.

‘Currently & Emotion’, edited by Sophie Collins

Katy Lewis Hood, Poetry Editor

2016 saw a boom in literature in translation, enabling a range of outstanding works to reach new audiences. However, such a rise is always in danger of obscuring the complexities of translation as medium and practice. ‘Currently & Emotion’ is a forceful, intelligent and stylish attempt to make translation visible.

The book itself is beautiful, with artwork by Canadian artist Stephanie Hier on the cover and bronze and red text inside. Right from the beginning, the visibility of translation is made political as well as aesthetic. “Currently, in 2016,†writes editor Sophie Collins in the introduction, “we are witnessing rapidly occurring and measurable changes in attitudes towards race, gender, and modes of representation.†Foregrounding work by writers not often included in anthologies – whether for reasons of race, gender, language, political orientation, or poetic style – and attending to the power dynamics of translation, Collins calls attention both to processes of cultural transmission, and to the practices that partake in, critique, and even transform them.

As well as an impressive range of poets and translators, the book features a variety of approaches to translation. Work is categorised as interlingual (translating from one language to another), intralingual (adapting a text within the same language), and intersemiotic (working between different artistic mediums), with some pieces incorporating all three types. Particular highlights include Chantal Wright’s experimental ‘translation-and-commentary’ of a German-language story by YÅko Tawada, Don Mee Choi’s forthright approach to the work of Korean poet Kim Hyesoon, and Khairani Barokka’s ’12 Acres’: an ‘accessible’ or ‘lateral’ translation of oral folk songs sung by women in an Indian village community into visual images.

At the end of 2016, finding means of border-crossing in language – of speaking but also listening to others, from the past as well as the present – is as urgent and necessary as ever. This anthology hints at the range of work already being done.

Braindead, created by Robert and Michelle King

Maryam Piracha, Editor-in-chiefÂ

Braindead, while officially cancelled, is the show that really defined the year for me. Created by the Kings—Michelle and Robert—who also created the smart, sensible drama, The Good Wife that ended earlier this year in May. The premise is wild: bugs from outer space invade the minds of senate and congress making them more extreme in their views, and enforcing partisanship across both sides of the aisle. This premiered during election season in the US, at a time when Donald Trump was a shiny twinkle in God’s eye. But in an odd sort of way, his election is a nice bookend to the show.

With witty performances by Mary Elizabeth Winstead (Scott Pilgrim vs the World, Mercy, Cloverfield Lane), Aaron Tveit (Graceland), Tony Shaloub, Danny Pino, Nikki M. James and Johnny Ray Gill, and a cast of other colourful characters, Braindead delivers an experience like no other in 2016. The hard to classify drama by The Good Wife creators and writing team, Michelle and Robert King, the show takes a satirical look at the current political climate in the US and offers one possible explanation as to why things are the way they are. The explanation, though outlandish (bugs invade DC from outer space and enter the heads of politicians and political evangelists, and eat one half of the brain), is a backdoor for the Kings to showcase the very weird, very antagonistic behaviour in a nation’s capital that paved the way for a Donald Trump presidency. It’s hard to pin down its genre, but it’s a romp and the performances are brilliant. The Kings join creators like Ali Adler, Joss Whedon (and Maurissa Tancharoen and Jed Whedon), along with Chris Carter and Greg Berlanti whose work I’ll gladly follow.

‘The Art of Rivalry’, by Sebastian Smee

Constance A. Dunn, Managing Editor

Smee’s new nonfiction follows four relationships between eight great master painters, from the beginnings of fond friendship, to mentorship, to the competitiveness that drove the creation of timeless masterpieces. The tragedy of ego plays out in these artists life, but so does poignant regret. Smee’s intimate details, well-researched and imparted with a fluidness only attained through years of study, turn the demigods Picasso, Matisse, Manet, Degas, Pollock, de Kooning, Freud, and Bacon into humans who loved, loss, had some success, but suffered along the way. These great masters, all of whom were able to transcend the trivial and mediocre on canvas, often struggled to find this same enlightened expression in their dealings with each other.

Rather than write the artists into little planets heedless of the many moons orbiting around them, Smee reminds the reader of the remarkable context in which each artist worked. The women that played such vital roles in the creation of the artists’ masterpieces were not forgotten, nor were the collectors, curators, and tastemakers that introduced the world to their work. It is refreshing to be reminded that the creation of a great artist relies as much on the world he or she lives in, as on talent and skill.

Smee’s style is smart, engaging, and avoids the heaviness of academic speculation in favour of the quick clip of long-form editorial journalism.

‘You Want It Darker’, by Leonard CohenÂ

Jacob Silkstone, Managing Editor

Perhaps appropriately, Edward Said left his collection of essays on ‘late style’ unfinished. Reshaped by Michael Wood, the volume — constructed around a course Said began teaching at Columbia shortly after being diagnosed with leukaemia — eventually appeared three years after the death of its author. Overturning “the accepted notion … that age confers a spirit of reconciliation and serenityâ€, Said was drawn to works of art that demonstrated “intransigence, difficulty and unresolved contradiction.â€Â

Leonard Cohen, Said’s near-contemporary, spent much of his career insisting that writing was enormously difficult. “I’ve often said,†he repeated in one of his final interviews, “if I knew where the good songs came from, I’d go there more often.†A week after the Swedish Academy chose to give Bob Dylan the Nobel Prize for “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song traditionâ€, the release of Cohen’s final album offered further evidence (if any were needed) in support of the argument that songwriting can be great literature.

Setting Cohen’s distinctive chthonic rasp against a minimalist background (acoustic guitar, violins, ominous but infrequent backing vocals from the Shaar Hashomayim Synagogue choir), ‘You Want it Darker’ often feels closer to spoken word poetry than to song. As a lyricist, Cohen is sometimes playful (“I struggled with some demons/ They were middle class and tameâ€), sometimes profound (“It seemed the better way/ When first I heard him speak/ Now it’s much too late/ To turn the other cheekâ€), but never content to settle for the easy option or the obvious answer.

Said wrote that Ibsen’s final works “tear apart his career and reopen questions that are supposed to have been resolved… tamper[ing] irrevocably with the possibility of closure.†In ‘You Want it Darker’, Cohen seems to veer between a desire for closure (particularly in the title song, which uses “I am ready, my Lord†as a haunting refrain) and a need to “tamper irrevocably†and reopen the age-old questions.

In his late interviews, Cohen expressed a readiness to die and a desire “to live for everâ€. His final album embodies both sentiments, and revels in being unable to reconcile them.

‘Yiddish for Pirates’, by Gary Barwin

Aaron Grierson, Contributing Editor

A parrot is the central character, Moishe. The parrot is a polyglot narrator with a forthright sense of humour and a love of language, regardless of which. My namesake (or am I named after the Parrot?) weaves a tale that defies all expectation. The book is even equipped with several historical cameos including Christopher Columbus, that genocidal Italian that went around exploring in the name of Spain.

I picked up this novel on a whim, it had an intriguing title. There is a lot of swashbuckling, romance, contemplation and commentary on a breadth of social issues that are still, sadly, relevant today, including the absurdity of discrimination against socio-cultural groups (including, but not limited to, Jews and Native Americans). We also get a rather close examination of some of the inquiry methods preferred during the Spanish Inquisition, one of the main settings early in the novel.

But it’s not all blood, torture and hatred. Oh no, sometimes you’ll find it hard to contain your laughter. As a lover of wordplay I was taken with this novel. Admittedly, I did not understand all the play and had to resort to some google-fu. Calling the parrot a polyglot is a well-exercised fact. If you love languages, this book might be worthwhile for that reason alone.

Overall, this is a work of ‘popular’ fiction. I understand why it was a finalist for the Giller Prize and shortlisted for the Governor General’s Literary Award for fiction. It’s a magically real historical fiction with a healthy sense of humour and the benefits of hindsight. It strikes me as a book even Mel Brooks would laugh at.

Planet Earth II, a sequel to Planet Earth produced by the BBC

Elizabeth Lee Reynolds, Nonfiction Editor

The arrival of Planet Earth II on our TV screens was a monumental event. Once again the charming and irreplaceable David Attenborough delighted viewers with insights into the natural world that would surprise even those who have devoured his previous work and thought themselves an expert. Of course, as Planet Earth shows, there is far too much left to discover about the world for one person to know it all. By presenting each episode focused on a different landscape the true diversity of the world was made apparent. We saw how the desert is in no way confined to the Sahara, how varied what we consider to be a forest can be, and even how wide the range of wildlife in our cities is.

The filming techniques allowed us to get even closer to the lives of incredible creatures, from snow leopards and city-stalking leopards to a harvest mouse and minuscule frog. When I was younger I used to always switch off when the ‘Diaries’ section was shown at the end but I know find it fascinating to see the dedication and years of work put in to bring us maybe five minutes of footage, where often the most basic techniques produce the best results. They created scenes that absolutely grip you, the tension and excitement created by newly hatched iguanas running from packs of snakes was more intense than any episode of Game of Thrones.

The strength and impact of this series was shown in the huge numbers which tuned in to watch it, with a surprising and exciting amount of younger people being drawn in too. I desperately hope that this means new generations are becoming more passionate about the natural world and will be readily joining together to protect it. This hope makes me wish even more that the environmental message of Planet Earth II was going to be a lot stronger. From episode one I was expecting something punchy and inspiring, an immediate call to arms to save a world in peril. Unfortunately, none materialised, but hopefully viewers will naturally write their own.