Poet, academic, editor, groundbreaking thinker — Arup K Chatterjee is a dynamic and apparently indefatigable writer, and his work manages to be both radically new and closely connected to a number of ‘influential predecessors’. In an extended Poet of the Month interview, he tells Rosario Freire why space is ‘the quintessence of [his] writing’, what epigraphs and intertexuality add to his work, and why ‘any kind of acceptance of hegemony is counterproductive to writing.’

It seems that physical space plays an important role in your poetry, especially urban space—as in ‘On a December Noon’ and other poems like ‘Pocketwatch’, based in London, or ‘Speech’, based in Calcutta/Bangalore. Why is this? What role do these spaces play in your own life? If you had to choose a city to place ‘On a December Noon’ in, what would it be (or is there a city already)?  Is the location of that poem deliberately left unstated?

It is true that space is the quintessence of my writing. I am a self-compelled exile, when it comes to writing (ab)out spaces, which are in fact the spaces I myself inhabit. The urban space, the city-space and the very concept of spatiality play an important role in all I conceive as writing. I tend to choose spaces as characters, not in the hegemonic sense of the expression: “whether space is character in such and such a novel,†but in a more eclectic and realist sense, as if to imbue spaces with the idiosyncrasies of human creatures. Space in my conception is always anthropomorphic. This is not to say that the poor little creature called space—which cannot speak for itself or represent itself—should be, or can justifiably be, seen in human terms. But it must certainly be allowed to exist, and be related to, in degrees of human alternations, such as moodiness, hysteria, iconoclasm, surrealism, temper, good skin, bad skin, fair skin, dark skin, even skin rashes if you will, and much more. This, for me, is a serious challenge. Architects understand the skins of buildings, as a painter understands the patina. The writer also must have some such responsibility. You might easily conjecture I am referring unconsciously to Kafka or Márquez; or, to the Dickensian squalor of the industrial revolution’s London. I am, but I also am not, in the sense that all these writers did eventually refer to grand epochs of history. I do not have the sense or precociousness to foresee an epochal turn. Like Proust I tend to get lost in the extraordinarily quotidian aspects, which in my case are nearly always the facets of natural or human landscapes, or architectures of human mobility.

In my poem ‘Karvat,’ I used the landscape of the Hoe in Plymouth—its local pub culture and fish and chips outlets—to create an Oriental narrative based on Sufi symbols, somewhat resembling a romantic exchange which might have occurred in Delhi or Lucknow in another time. It was necessitated by my own need to live in that space which I tried to construct to the best of my ability. Without the creation of this mental landscape I would be in the throes of a severe exile.

To me space is necessarily urban, for there is a technique, after all, both in the pastoral-rural and the urban with which we build the heim (home). That inhabitable space, leading to the congregation of the merchants and vendors, to the agora, is therefore always tending towards the urban, at least in a philosophical sense, and certainly for literary purposes. These spaces, where my writings supposedly reside, are also my dwelling places. Whenever I encounter the unheimlich (the haunted home) I tend to build a new heim, therefore a new literary space. Needless to say a writer, in pursuit of characters, must be a good observer. In my case, wherever I fail to engage in a meaningful conversation with people I try to compensate by having one with spaces, which have in turn been built, trodden upon, nurtured, or neglected by generations of cacophonies of hundreds of voices.

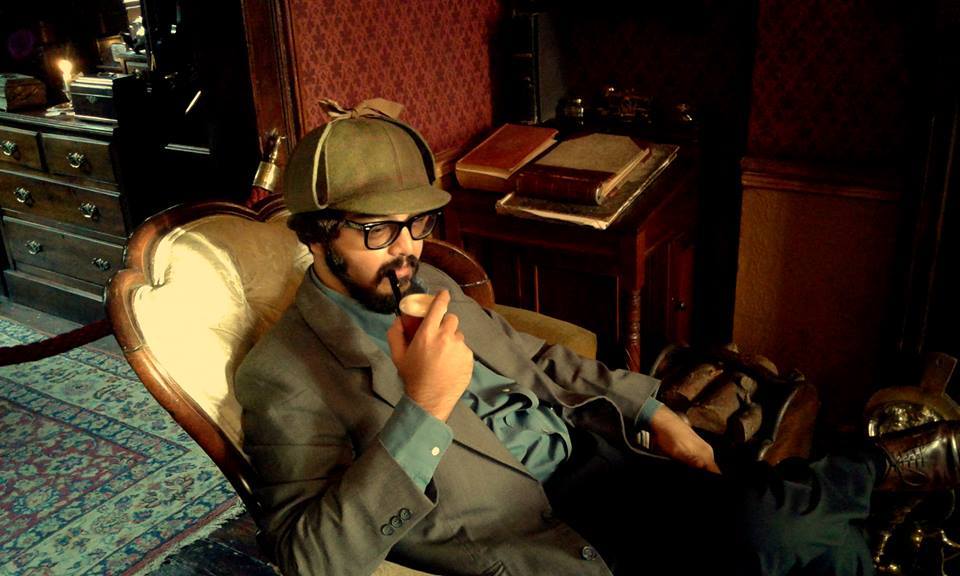

‘On a December Noon,’ as hinted in the epigraph, is intended to abide in a heim shared with another great vocalist of space—Boris Pasternak. Being about exile, in many ways, ‘On a December Noon,’ is about Stalingrad (or what it might have been), a city I’ve never visited, and my study table where most of my flânerie occurs. The formal model for the street and the architecture is a street in London’s Baker Street where I spent some hours reading from, and decoding, the nighttime representation of places in the vicinity in ‘The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes’. It is also about Delhi, which does receive very cold winters, if not snows. And, finally it is about going upwards in(to) a coffin rather than being buried down, as is oftentimes the custom.

What inspired ‘On a December Noon’ and what inspires your poetry in general? How often do you use your own experiences—things you heard, or saw, or read?

It was inspired by ‘Doctor Zhivago’. It was also part of a dialogue that I have begun with voices that articulate melancholy, the voices of Pasternak, Eliot, Hardy, Lawrence, Gray, going back to a host of other graveyard poets of the eighteenth century.

Most of my writing works on a principle of reality which is ironically based entirely on previously written fiction or poetry. My writing can only be in response to writing. Often I even suspect I am only rewriting what others have written before me. There could be many ways to justify any singular or generic act of writing, and one very useful justification—although I disavow any utilitarian purport in writing—is that it creates new turns in language, in discourse, in sensibilities. Today ‘sensibility’, in the more complex understanding, refers to taste or aesthetics. Samuel Johnson however defined the word as ‘sensitivity,’ which certainly takes this to a level of rationality and enlightenment. I believe enlightenment cannot be restricted to any particular age, or icon such as the Buddha, or claimed to have been complete in the eighteenth century. And since it must go on, I must also go on writing despite rewriting, in a new language each time I write. In this regard, the reality principle is very crucial, since what is read or heard on the streets—as I have realized more so of late—very often seems absolutely unreal. The utter irrationality of quotidian lives—idleness or unemployment which breed magical realist autobiographies that were never written down—in all that we speak which when taken out of context has begun sounding more and more anomic, technologized, immutable in that it does not lend itself poetically to be borrowed, literarily transubstantiated, or even plagiarized, because most of it is so immediate. Voices overheard or radio voices, voices I read or listen to reading occasionally on the radio or upon a stage are so divorced from that rather benevolent pretension of universality. Writing and speech are no longer afraid to be rigidly bound by immediate landscapes and contexts. This is as irritating as it is challenging for a writer: to glean from the spoken and the written word that has come before my own requires great consistency of the reality principle. So, yes, while things may be really happening and be spoken and be enacted in real lives, their ring of truth is certainly lesser now in the written space, and while I am given entirely to engraving real life imagery and speech into my writing, upon the cartilage of literary traditions, I must now pay all the more attention to the shrinkage that the universal contexts of our articulations have globally undergone.

Most of your poems employ epigraphs and/or quotations from other poems —could you give a sense of what this intertextuality adds to your writing? Do the quotations usually inspire your own poem, or are they chosen once the poem has already been written?

The answer to the second part is simpler: sometimes the quotations are chosen prior to the completion of the poem, and sometimes much later.

I would like to say three things regarding the use of epigraphs in my poetry. Firstly, I hope to inspire, someday, some vision of pedagogic value in my writing. This is so because the epigraphs are primarily portraits or frames which bind the poems underneath them. Every poem is written like a picture composition, a very common nineteenth century practice, as well as a now-depleting pedagogical resource. I like deploying a sort of roman à clef wherein I try to both conceal and reveal—in short encode the principle of reality—in the epigraphs I choose. I have always enjoyed and heard of people doing the same while reading literature that makes the use of a key. The trick is to alienate the persona enough so as to not allow even the most familiar reader to locate identities of people or spaces from within the context of the poem. Else, the writing is reduced to a meretricious cipher. The epigraph however will always lead back to something very intimate which can unfold—for the psychoanalyst for instance—the entire sequence and plot of events on which the given poem is based.

The most singular reason I can cite for these epigraphs is one that comes from my academic sensibility. As an academic I am very attracted to the use of epigraphs in esoteric essays which practically no one reads. Somehow it adds a lot of aesthetic value to the appearance of the text of the essay. On a more serious note, the academic essay has the provision of footnotes, endnotes, in-text citations and so on. The poet has none of those privileges. Rather, the poet is deemed to be free. Even if he wants to refer to another writer he is condemned to not be able to cite. The epigraphs are part of my own technique of poetic citation.

Often I discover such irrevocably magnificent lines—sound-images, prepositions, adjectival nouns—in poetry which I cannot help but reproduce almost in entirety. In my poem ‘Al-Hijr’ I wrote the following lines:

Where do I go with such visions of the rails

which the philandering rail hardly comprehends—

soiled, dismembered, remembered compartments

The sounds and the nostalgic dilettantism of the love-object were directly drawn from Eliot’s “You had such a vision of the street/As the street hardly understands,†in ‘Preludes’. The very first stanza of ‘Al-Hijr’ bore the line “La lune ne garde aucune rancune—,†which was also meant to draw attention to Eliot. As regards the epigraph of the same poem, which is from Philip Larkin’s ‘An Arundel Tomb’ the lines “On a rain-littered platform they arrive/endlessly altered from a long ziyaarat/ from a desert mazaar or Arundel tomb†are once again very directly meant to resonate with Larkin’s “Light/ Each summer thronged the glass. A bright/ Litter of birdcalls strewed the same/ Bone-riddled ground. And up the paths/ The endless altered people came, Washing at their identity.†Such lines create such indelible impressions on my mind that their strong visual impact commands from me a poetic citation. Eliot’s “I am moved by fancies that are curled/ Around these images, and cling:/ The notion of some infinitely gentle/ Infinitely suffering thing†also had a similar effect and I used it as an epigraph to my poem ‘Karvat.’

You’re the Founding Editor of an International Journal of Travel Writing, Coldnoon: Travel Poetics. The journal’s website states that “Any book that travels across national borders, via online book stores—any letter, an email itself—carries potential threat to a previously established and hegemonic travelogy. In this sense any written word that talks of motion or itself moves via means of transport is travelogical and political.†Could you give us some examples of poems (or other texts) that become political by ‘talking of motion’? How important is it that your own poems carry potential threat to previously established and hegemonic ways of thinking?

I must take the liberty of explaining what travelogy is. This is a neologism. I have noticed some people have already begun using that word without any knowledge of what it entails. There are travel agencies called “Travelogy,†and I would therefore link the academic concerns and intellect of the casual user of that word and the travel agent as identical—as nil.

First of all, travelogy has no connection with travelling at all. It simply is how much home (heim) does one create. In order to construct this home travel is indispensable. One travels physically or through prostheses. Architectural forms travel, commodities, culinary cultures travel (which in turn shape architecture is a major way) ideas travel, the planet itself travels every day. Some of us do not create any home whatever, some of us simply consume, hedonistically. However, this perhaps is only theoretical. No one can entirely create or consume. I am given to the sentimental idea that there is always that vestige of production or consumption in the most consuming or producing agency. This is to say, the native or the aboriginal who constructs a narrative or space is also consuming it to some extent, and the blasé tourist—who according to Lefebvre plays no role in the production of space—is also after all adding to the semiotics of the landscape.

Henri Lefebvre’s ‘The Production of Space’, Gaston Bachelard’s ‘The Poetics of Space’, and Michel de Certeau’s ‘The Practice of Everyday Life’ are the most well-known examples to me of full length works on space and travel which encounter very politically the ideology of travelling and arbitrariness of spatial codes, wherein the spectre of capitalism and tourism is inherently destructive to the oneiric (daydreaming) potential of the traveller or the dweller. Certeau, for instance, writes that we travel to revisit lands which have become alien in our own homesteads. A late eighteenth century example of this semi-parodic mode of travelling—urban travelling, flanerie, interior travelling—is Xavier de Maistre’s ‘Voyage autour de ma chambre’ (Voyage Around My Room, 1794) which provides a prototypical example of modern day psychogeography along with being a parody of the grand travel as witnessed in the early eighteenth century narratives of space, colonialism and discovery in ‘Gulliver’s Travels’ and ‘Robinson Crusoe’. In poetry take Rudyard Kipling for instance. An enthusiast for the Indian railways, he left in his ‘A Ballade of Burial’ a plea for settling down in the Indian hills

Solemnly I beg you take

All that is left of “I”

To the Hills for old sake’s sake

The above is political because of the increasing industrialization of the cities and in nineteenth century India, coupled with the colonial conception of the “noble savage†being the true aboriginal of the hill stations. These sites later became the laboratories of colonialism, where the memsahibs bred Victorian manners in situ, and the whole paraphernalia of the British Empire was relocated to for half the duration of the each year. On the one hand the politics of hillmaking is offered an incentive in the words of Kipling, and on the other the English nationalist melancholia of the graveyard poets returns in the travelogy of Kipling.

My own writing, needs must be writing first of all—it must be singular, self-conscious, even belabored. Since it is always in response to previous writing it must distinguish itself at the same time as imbibing from the latter. I cannot say that I have managed, or will manage, to threaten established forms and norms of writing or thought. Neither do I set out with such a motive. However, I do consciously work on language and try to generate newer mechanisms of naming, of the verb, and of imagery. Even in the examples I have named above the writers found themselves pitted against enormous hegemonic ideologies. There is hegemonic attack on mine as well. There is, as some say, no poetic rationale behind the epigraphs, some others blindly criticize the use of footnotes and the import of foreign languages into English poetry. For some it is immoral sexual content. Any kind of acceptance of hegemony is counterproductive to writing. Acceptance is not sustainable. One has to keep writing back to hegemony in language after language. The moral, law abiding, and conscientious reader also needs an inducement to come to your bohemian literary cafe. As a writer I am always threatened by the idea that someone would steal my thought or writing and present it before a larger readership than I could. In this way, all writing that has come before me must necessarily be under the threat of being represented in a new language, rewritten, for there is simply nothing we can produce that is new. We can only speak another tongue after all the tongues at Babel were severed.

What do you make of Thoreau’s statement “I have travelled a good deal in Concord†(from ‘Walden’)? Does travel has to be across geographical borders, or can it be purely an act of the imagination (as when Des Esseintes ‘travels to London’ in ‘À rebours’)?

This is a question after my heart.

Actually, the laboring man has not leisure for a true integrity day by day; he cannot afford to sustain the manliest relations to men; his labor would be depreciated in the market. He has no time to be anything but a machine. How can he remember well his ignorance—which his growth requires — who has so often to use his knowledge?

Travel also is a kind of labor, or at least that is how it is understood by most—a kind of mindless labor. It is trekking, hitchhiking, rock climbing, lavish spending and leisure holidays (the latter which in turn subsume the labor of an invisible force forfeited to capital). The amount of capital invested in travel blogs and online hotel brochures is staggering. Ironically it is part of a parallel universe, the worldwideweb, where the idea of travelling or flânerie is yet to be explained to the world at large. These thrive on the ideal of alternate travelling. But what is it that the traveler produces? We are not talking of Jack Kerouac for whom the road was a home. We are talking about aspiring individuals who are here to stock social as well as monetary capital. Since when did travel become a passport to social mobility? Since forever ago, because the idea of travel was fraught with opportunism and imperialism at its very inception.

‘À rebours’ is a wonderful critique of the dilettantism that is a de facto enticement behind travelling. It is a fine specimen of literary travelling. In the specific example of travelling to London, which you mention, Des Esseintes demonstrates how the space created by Dickens is not simply fiction after all but the essential cognitive space that all the Londoners might exist within, in the Frenchman’s conception. Joris-Karl Huysmans writes of Des Esseintes dining in an English restaurant in Paris, while the latter waits for his train

A feeling of lassitude crept over Des Esseintes in this rude, garrison-town atmosphere; deafened by the chatter of these English folk talking to one another, he fell into a dream, calling up from the purple of the port wine that filled their glasses a succession of Dickens’ characters, who were so partial to that beverage, peopling in imagination the cellar with a new set of customers, seeing in his mind’s eye here Mr. Wickfield’s white hair and red face, there, the phlegmatic and astute bearing and implacable eye of Mr. Tulkinghorn, the gloomy lawyer of Bleak House… The Novelist’s town, the well lighted, well warmed house, cosy and comfortably appointed, the bottles slowly emptied by Little Dorrit, by Dora Copperfield, by Tom Pinch’s sister Ruth, appeared to him sailing like a snug ark in a deluge of mire and soot. He loitered idly in this London of the imagination, happy to be under shelter, seeming to hear on the Thames the hideous whistles of the tugs at work behind the Tuileries, near the bridge. His glass was empty; despite the mist that filled the room over-heated by the smoke of pipes and cigars, he experienced a little shudder of disgust as he came back to the realities of life in this moist and foul smelling weather.

Why that shudder of disgust? Is it because Des Esseintes finds it all too contrived insofar as fiction had begun mediating his realities? Well, that is true of any regime, any epoch. You need a fiction to experience reality, for the latter is only a reflection, and not the obverse as is touted before schoolchildren. But the point easily to be missed here is Des Esseintes’ overwhelming realization of the futility behind travelling to (literary) places unless one is capable to producing one, or at least nurturing it, rather than ordering for it to be served on a platter, in proxy, in a foreign establishment. He hence foregoes seeing merit in being a “naturalized citizen of London,†after the disillusionment that Dickensian dramatis personae stage before his eyes.

The fact, to conclude, is that neither imaginative nor physical travelling are travel narratives of the human spirit: both either follow a technique (as in writing, and reading) or a mechanization (as in the digital reproduction of places in brochures and travel blogs). What is, however, the most ecological system of travelling is the construct of the heim in relation to its universe. The heim is anthropomorphic apropos the individual self, and the experience of the unheimlich (the haunted house, or the place outside of congruent space, as experienced by Des Esseintes in the English restaurant) is mediated by a difference of spatiality. As a consequence human forms, norms and emotions follow spatial codes, or possess a certain spatiality, and spaces themselves have anthropomorphic responses to human stimuli. Travelling is the negotiation or the dialectic between these two—the heim and the unheimlich. Descriptions of exotic places, travel packages and tours to villages tucked away in isolated landscapes do not cut much ice in my imagination. I am obsessed by that one sentence I would often encounter in Chemistry or Physics lessons in school: “An electron is travelling at the velocity of…etc.†The electron is the reactive constituent in covalent bonding. It is a transient Heimlich, and yet the bond is stronger than electrovalent bonds. Likewise we too, unbeknownst to ourselves tend to bond with spaces by sharing our own valences. This scientific model does work very well, and I am neither trying to be a spiritualist or a positivist. My equation is simply about the home and the universe, and in methods one can take to visualize itself through elements of another; hence the dialogue between spaces, going inwards into the heim within, and taking the heim beyond the confines of geopolitical borders. No, travelling is not about border crossings, it is about striking co-valence with spaces and their characters. What I see as a narrative of food, fashion, architecture, and luxury, not even well-decorated (not even as durable as the picturesque British narratives of Indian hill stations which go into the making of tourist brochures till today) is not travel, what I see as a photograph posted on social media incipiently declaring “I was here…†is not even tourism, it is conquest.