By Arturo Desimone

Performances of Kingdom of Fire and Clay toured in Holland, Prague and in the UK, (at theaters such as The Cockpit (London) Melkweg (Amsterdam) and Podium Mozaiek (in Amsterdam) from 2013 until the show’s last performance in November 2015 at the Amsterdam Wharf.

His friend, an Iranian refugee in the Netherlands, Sahand Sahebdivani (also playing himself) talks about the devastating Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s. He reveals how his father, an Iranian ex-communist, as a young man once toyed with the idea of going to fight in Palestine against the Israeli army — a popular gesture of solidarity among many Iranian Communist Party members of the time. The Israeli jumps back in astonishment and shock. Later on, it seems the Iranian refugee children also get their heads filled with exasperating and traumatising histories by their parents, who often have no one else to talk to in exile, feed the nightmares of Persian children.

The Israeli is brought closer to his catharsis by the Persian, who, dervish-like, is his mentor and as a wise older brother, corrects Rodan’s misgivings.

“But do you think we are monsters? Do you think I am a monster?†Rodan demands, confronting his co-player with fuming eyes in one the play’s most confrontational moments.

*

Sahebdivani has often performed solo as storyteller — a minstrel in the tradition of Iranian itinerant storytellers, who today still roam from village to village in the Khorasan valleys of Iran saddled with fables. Sahebdivani inherits the tradition from his father (a traditional Iranian wayfaring teller who was hired by the now extinct Communist Party).

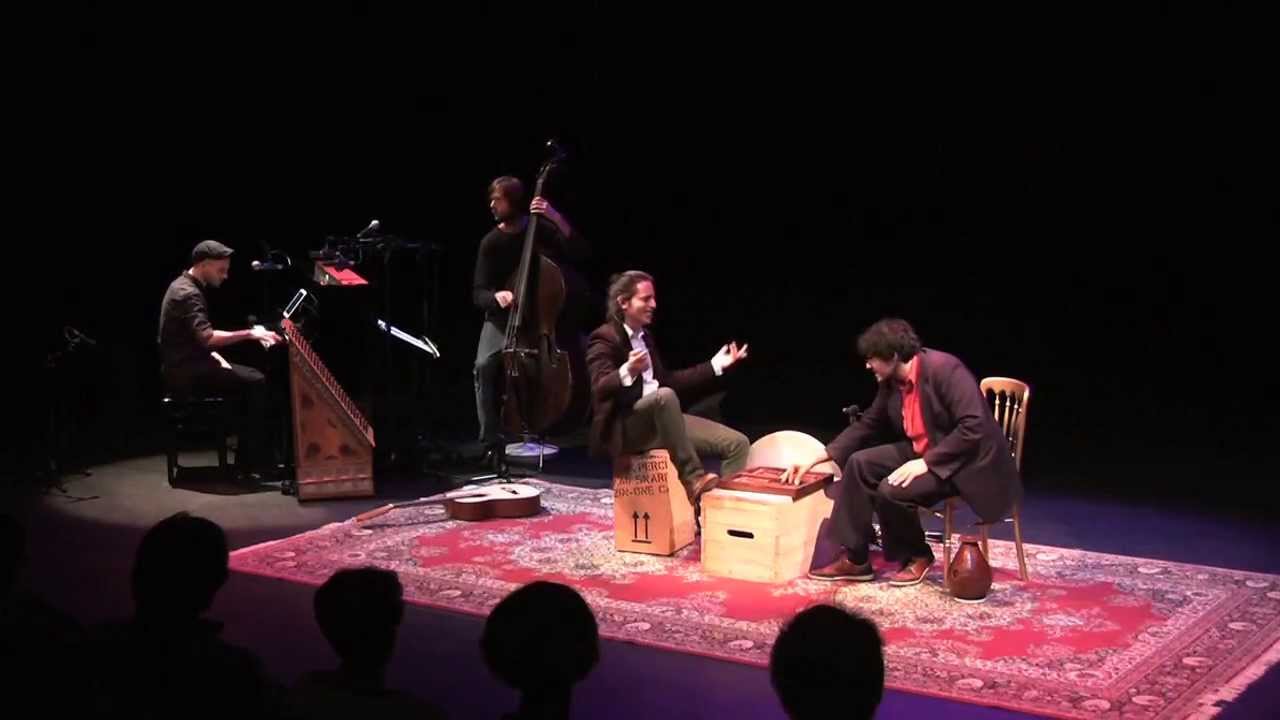

Israeli musician and performer Rodan co-founded the International School of Storytelling for Peace. An orchestra of musicians also accompanied the duet. Tales from Persia and East-European Jewish folklore were charismatically recounted, together with musical performances from the backup orchestra: these were the high points of the show. The Persian strongman Rostlan (a king who resembles the Greek Heracles or the Jewish Samson) faces off with the mythical Golem from the lore of Eastern-European rabbis. This cocktail of theatrical disciplines, at times vibrant, at times a bit glib and cutesy, satisfies the usual audiences attracted to the subcultural underground of ‘’storytelling’’.  In the hands of less inspired performers, the “storytelling’’ model, attempted weekly in Sahand’s own café by his students and clientele, quite often amounts to insecure stand-up.

It shows that Kingdom of Fire and Clay’s charming, yet hyper-political, formula may have been conceived pre-Iran-Nuclear-Deal, when diplomacy between Iran and Israel stood embroiled in a cold war and saturated the global news. All the while, the two peppy characters that are the focus of the story meet in Amsterdam over a game of backgammon, an ancient game played by their immigrant forefathers. These men begin by trying to be friendly, though it is unclear as to whether they have known each other for years or have only recently met.

Inevitably, friendly intercultural banter and sentimental, personal exchanges are traded in turns. These are at first awkward, but quickly become explosive. The friction begins because of cultural differences that can be tricky to reconcile, but it’s clear to the audience that there are just as many striking similarities. The desired effect is, by the end of the piece, to have demonstrated how many of these similarities exist between the culture of an Iranian refugee in Europe and that of an Israeli-Jewish son of refugees from both Europe and the Middle East.

Perhaps the performers’ own diverse backgrounds help them confront these differences and similarities in a more practical way than some of the audience they hope to reach. Actor-musician Rodan’s origins are diverse, a mixture of eastern-European and Middle Eastern Jewishness that has become typically Israeli by now. His grandparents were Persian Jewish immigrants to Israel, who intermarried Ashkenazi European Jewish immigrants who lived on the settlement communes known as ”kibbutzim”, an early socialist experiment founded by the more ideological Zionists who went to Palestine during the early 20th century. Also, the similarity in family dynamics is addressed. Throughout the piece, both young men express awe and amazement for the women in their families — their mothers in particular. So, Jewish men, as well as Arabs and Iranians (and not altogether unlike Italian men), live in fear and amazement of their mothers? Of course, we fight because we are so frighteningly similar. If only this was more well-known before the Iran nuclear deal, perhaps then Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu would not have threatened suicide in protest.

The action takes place over a game of backgammon in a traditional teahouse. This motif of a battle in a teahouse between an Iranian and an Israeli works. In Western Europe, the iconic teahouse serves as a drinking bar for Muslim immigrant working class men, where they unleash their worries, hopes and anger in conversations over na’anna tea and backgammon. It is a place of intimacy and negotiations. In the popular culture of the Netherlands, drinking tea strangely acquired a connotation with multiculturalism and with the ‘’multicultural experiment’’ of the 1980s and 1990s, years of Dutch welfare-state prosperity, a project which a large part of the centre-right constituency has outspokenly denounced to be a proven disaster, for reasons seldom made clear. The immigrants did not fade into total invisibility, nor did they all become middle class Calvinists overnight, nor did they return en masse to their past homes to accommodate the Dutch during a period of minor economic recession in the Netherlands: the multi-cultural project, symbolised in Holland by the teapot of Dutch illusions, simply shattered.

To add atmosphere to this setting there is the music. Further tension is added by the skilled musicians with bursts of sound that weave in and out throughout the storytelling. The musicians who accompany Sahebdivani and Rodan — musicians themselves — sweep the audience away with the passion of their playing and their accomplished technique, allowing the stories to emotionally transport the audience.

Unfortunately, there is a prevailing, and deeply annoying, sense that some of the most important drama was purposely avoided, in order to focus on tolerance. Tolerance, which has altogether vanished from the Netherlands, rules the other Kingdom. This is well in accordance with the aesthetic dilemma of the early new century, where it is insisted that art provide the hyper-politicised sentimental utopia of the broken promises of progressive political establishments. Art has become the one place where democracy’s yearnings are satisfied. Radical playwrights of the 20th century such as Arthur Miller, Sartre and Tennessee Williams did all they could do destroy the illusions of middle class democracy, denying the crowd the satisfaction of its own tricks. Though Federico Garcia Lorca’s social life may have included tolerant bohemians who accepted his homosexuality and nonconformity, the subjects of his plays where usually Spanish peasants and conservative families, whose threatened traditions and prejudices generated tragedy.

In Kingdom of Fire and Clay the highpoint of the conflict remains at comedy, such as during a fight where Rodan slaps the floor. No insults and no racism, no anti-semitic prejudice, no anti-Muslim prejudice. If Rodan did his military service in Lebanon, or in the territories, it seems his character did not, as it goes unmentioned. Rodan’s trauma is his Israeli holocaust education, but he mentions no anger at Iranian politicians’ stand-up routines promoting holocaust denial (or ‘’questioning’’ as former physicist and ex-president Ahmadinejad liked to call it, as if describing a physics problem). Similarly unmentioned are the Iranian attitudes towards Arabs — usually these are not all that favourable, except when it comes to statements of solidarity to Palestinian victims of the “enemy” state.

Both characters, before the show begun, have already dealt with every fear or resentment related to the state of cold war between the two countries.

This lapse is a lamentable result of how the political opinions of both characters on stage happen to be exactly the same as their political beliefs off stage (maybe they are even nicer on stage). The meeting of the minds of the two characters Rapheal and Sahand play, reveals them (the performers), sadly, for exactly what they are: two extraordinarily progressive, open, well-travelled artists, nice-guys who have become as well-informed as possible about the other’s people. Both of them probably spent their lives crossing paths with other progressive, bohemian and open-minded young Iranians and Israelis. Where there could have been a dramatic conflict, alas, there is instead, a comedy of exceptions. At the very best, the audience saw an informative, feel-good spiel that attempts to advertise diplomacy between Iranians and Israelis.

Most of the conflict is embodied by the characters being very annoying to one another, and this annoyance stands in lieu of the nitty gritty emotions that are possible in theatre (i.e. fear, anger, hatred, desire, violence, racism, insanity, prejudice, wanting to have each other’s mothers and sisters, et al).

Kingdom belongs to a genre of performance that has come to express many of the Israel-Palestinian collaborations in music, cinema and theatre. In this form, conflict and accusation (usually between an Israeli and a Palestinian, or two Balkan ethnicities) is completely avoided though it is fertile material; instead, a fruitless cute brotherhood bond is imposed upon the characters.

Both Sahebdivani and Rodan are clear exceptions to the rule in the real world, all too willing to learn about one another’s worlds and to make a show of tolerance, the kind that proliferates theatres elsewhere in the Western world as a form of well-meaning democratic agitprop preceding the successful consolidation of the US-Iranian Nuclear-Deal, in which Israel played a crucial role by showing itself to be unreasonable. (The deal was protested so belligerently and idiotically by Netanyahu — who showed himself to be a far greater man of theatre than any Iranian or Israeli semi-professional).

It is quite arguable that cultural events big and small — including the British museum’s violation of Cameron’s sanction politics by exchanging a large exhibit with Tehran in the crucial year of 2014 — all became part of the props and international backdrops of diplomacy for the deal in the years leading up it. Part of this massive cultural backdrop might have even included Shirin Neshat’s The Tempest, an austere and mightily funded production of Riefenstahl-like aesthetics, performed at the Amsterdam Stopera and other international opera-houses. (Neshat’s title was misleading, as it had almost nothing to do with Shakespeare’s Tempest — unless Caliban was lurking somewhere behind the scenes).

Throughout Kingdom of Fire and Clay, Sahand seems in the position of a wiser, more mature friend, an older brother who has experienced forms of serious discrimination as a refugee in Europe, Iran and Turkey. Rodan, meanwhile, is an innocent who tends to imagine anti-semitic dangers lurking: in a sense, a stereotypically naive young Israeli with a penchant for exaggeration. His dialogue with Sahebdivani becomes almost a form of therapy: “We were almost threatened with existential destruction! Look, America attacked Iraq!†Rodan says excitedly over the backgammon board.

“Wait a minute —“ Sahebdivani inquires “let’s see if I get this — Iraq got attacked, not Israel. Iraq here, Israel there: how did this threaten you?â€

“Well it’s mighty close!†Rodan gushes comically, as Sahand mockingly corrects him.

Sahand explains that Iraq once invaded Iran, unleashing the terrible Iran-Iraq War with many casualties, Sahebdivani eloquently and clearly informs his audience. He also stages, without any irony or artificiality, that recurring tendency of Iranians to consider themselves the first and foremost victims of the state of Israel, or in any case somehow more intimately related to the destiny of the Palestinians than other bystanders. That paradoxical Iranian illusion remains not merely central to the play, it is also central to all discussions by Iranians about Israel today outside of the playhouses.

Sahebdivani’s character recounts how the Iranian communists of his father’s generation dreamed of going to the West Bank to join the Palestinian guerrilla fighters in resisting the Zionists during the 1960s. But his own father did not have the honour or the luck to join those guerilla fighters.

The Iranian exiles in the arts, public life and academia who educate liberal and progressive Western audiences about Palestine, seldom allow for any exploration of the all-to-common Iranian cultural racism towards Arabs. European Christian anti-semitic stereotypes of the Jews are a relatively recent importation to Iranian culture, and still new there, though they have gained much ground during Ahmadinejad populist era’s cult of political entertainment.

How would the Iranian’s pro-Palestinian posturing sound to an Arab from the Ahvazi region in Iran? Where Arabs are often systematically killed by the Iranian government because of the Ahvazi regional resistance movements? A recent victim of such policies was Hashem Shaabani, a young politician for the Ahvazi cause and a poet, executed at the age of 32. Shaabani, founder for the Dialogue Institute (based in Iran) promoted the interests of Arabic-origin Iranians, and his letters from prison to his family attested he could not remain silent about the state-terror against Ahvazis.

A theater of diplomacy, which prioritises how to correct a stereotypical or mistaken image about a maligned country, or about misunderstood groups, to a Western audience would not work in this case if the audience included Ahvazis.

Tennessee Williams’ or Lorca’s plays remain political art regardless of the ethnic origins of the audience, as they are not made solely to illustrate diplomacy, or are dispatching cultural envoys.

The problem with political art that engages with the discourses of integration-politics and international diplomacy, is that art, music and the theatre cannot hold onto aesthetic power while serving as a prop to express euphoria about these programs.

Neither the anti-Arab racism of Israelis, nor the very different anti-Arab racism of Iran gets serious treatment in the play about brotherhood between an Iranian and an Israeli in the safer surroundings of Amsterdam cultural centres. It is an unfortunate cosiness. The storytellings of Persian and Jewish folk tales are wonderful and full of emotion. Comparatively very little imagination went into fictionalising the surroundings of the two main characters, which is a pity.

Perhaps the problem in mixing theatre with the performance style preferred within the Amsterdam Storytelling Festival, is how the latter form prefers this cosiness, whereas theatre likes cruelty — a “Kingdom of Oil and Water”.

Luckily, the stories that are interspersed throughout the play do have some more adventurous and politically incorrect content. Both Persian and Jewish folk tales are recited, as well as the personal biographical stories of Sahand’s parents, their love-story and their emigration from Iran, as well as the story of Rodan’s mother and grandmother who eventually emigrated to Israel.

The duet tries to cast Israel as ”the golem” in the famous Jewish folk tale from the rabbis of Eastern European countries. It goes like this: The rabbis in a village of European Jews made a golem, a monster they formed from clay, who would defend the oppressed Jews from the violent anti-semitism of the Polish Catholic aristocrats and peasantry. But the golem, an enchanted automaton and war-machine, then outlived his purpose, wreaking havoc and laying waste to all in sight, over-protecting his people and eventually harming them. This tale brings us to the enthusiastic conclusion of the piece.

Here, friction arises between the forms of the storytelling — one which invites the audience into a cozy living room for tea, the other inviting them to witness a piece of political theatre. In theatre, one would hope for an actual golem, a disturbing entity, perhaps in a funny costume, wreaking havoc, storming on to the stage.

Combining the two forms and blurring the borders is certainly a worthwhile endeavour and hopefully more interesting shows will emerge from the duet.

Arturo Desimone‘s poetry and fiction have appeared in Hamilton Stone Review, New Orleans Review, Jewrotica, Small Axe Salon, The Missing Slate and the Acentos Review. He was born and raised on the island Aruba. At the age of 23 he emigrated to the Netherlands, and after seven years began to lead a nomadic lifestyle that brought him to live in such places as post-revolutionary Tunisia. He is currently based between Buenos Aires and the Netherlands.

[…] My review of the Dutch-Iranian-Israeli play ”Kingdom of Fire and Clay” published in The Missing Slate literary magazine. http://journal.themissingslate.com/2016/03/03/the-kingdom-of-fire-and-clay/ […]