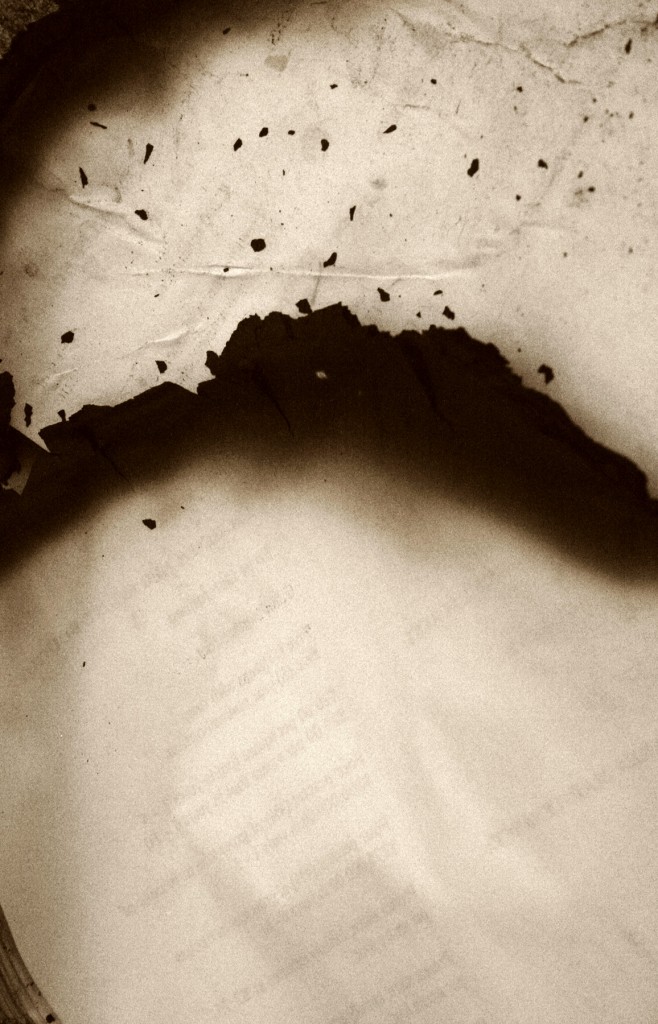

When Novels get High on Fire. Photograph by Brett Stout

By Jesús Urzagasti

Translated from Spanish by Jessica Sequeira

Late at night, silent, the consciousness of his work surprised him.

A book. He can’t remember the first time he felt the need to write a book. What he’s never forgotten is that in his case, the possibility of a book came not from the curves of mental calculation, but the difficult course of a life and what’s lived. At some other time he was able to appreciate deeply and without envy those able to logically produce a text. But he also knew that for him, the only possible literary dialogue came from previous self examination followed by comparison with nature — or the opposite, or maybe both at the same time. The song of a bird for example, which in its eternal present condensed the memories of voiceless trees. This formed part of a much larger map where it seemed difficult to orient himself, since he was also included as an observer and detached partisan of objectivity. Later came the dreams, a complicated light that left no vanity safe but the delusion man is completely responsible for his actions. Then his vast gaps in knowledge, a fact that inclined him to clear thinking, the kind that didn’t escape over slippery unknown terrains but moved over fields where his presence was no obstacle. The first time he managed to write a book, he had to convince himself the ease of writing had its equivalent and counterweight in the hardness of past learning. “I know it’s different for others” — he said with respect — “but what importance do others have in my night and day? So far as I know, none.” He chose what he was allowed to choose and experienced the happiness of writing a brief period, which in the real course of Time lasted from February 23 to June 13, 1967. More than a decade later at midnight, between December 31, 1980 and January 1, 1981, after a break from words and a serious challenge to his body, he started another book. This volume has now been concluded — though he still hasn’t managed to read the date at its end — just as Life is concluded in Death. Late at night, silent, the consciousness of his work surprised him. Terrified, he told himself that “to finish what’s been concluded since the beginning of time requires courage and lucidity, and daring and prudence, since the mere proposal of such a task is an invitation down the path of madness. Nothing convinces me I have the virtues necessary to resist the danger of such a precipice.” He knows something has already been concluded — in this case, a book still only half-written — yet isn’t able to decipher its ample and total meaning. It becomes a difficult exercise for the memory. Now he lowers his gaze, withdrawn from the world and absorbed in his writing. He wants to avoid the first and never renounce the second again. The problem can’t be solved since it has multiple solutions, which he’s made hang together in this way: by inscribing writing in writing, and life in life. In other words: what’s living in what’s already happened, and life in death. Any word just pronounced, he thinks, adds itself as a tiny but essential part to the largest, most detailed, most general text called the Finished Work. Paradoxically that finished work always demands the absent term, word, concept and accent. In the same way death demands of each organism the trivial gesture, surly walk, violent decision, and survival of life in each tiny act, to complete its final objective: the cease fire, the truce of disappearance, the radiant silence amidst so much darkness.

Jesús Urzagasti was born in Campo Pajoso and wrote ‘tirinea’ and ‘de la ventana al parque’.

Jessica Sequeira is a writer and translator living in Buenos Aires.Â